Planet LHS 3844b, a terrestrial exoplanet orbiting a small sun 48.6 light-years away, has no detectable atmosphere. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC)

Prospects clouded for finding life on the largest class of planets

Discovery of a planet without an atmosphere bolsters concerns about bodies orbiting stars smaller than the sun

Most of the terrestrial planets in the galaxy orbit stars smaller than the sun. Because of their sheer numbers, they would seem to be promising candidates in the search for life elsewhere. But astronomers say they suspect that these bodies — especially ones in close orbit — are vulnerable to losing their atmospheres, necessary to support life. The discovery of one such planet beyond the solar system with no atmosphere at all clouds the prospects for its peers.

Those findings were detailed in a study led by Laura Kreidberg, a Clay Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). In it, researchers show that planet LHS 3844b, a terrestrial exoplanet orbiting a small sun 48.6 light-years away, has no detectable layers of gases blanketing it to protect it from its sun’s dangerous radiation and trap its heat. A planet’s atmosphere makes it viable for hosting life and provides telltale signs of whether it actually does. It is also key to understanding a planet’s origin, nature, and current conditions.

“We’ve learned over the last decade that planets similar in size to the Earth are abundant around other stars — which is crazy exciting for the prospects of potentially detecting life on one,” Kreidberg said. “However, just because we know these planets are out there, we don’t know anything about whether they typically have atmospheres or not.”

The results, described in an Aug. 19 paper in the journal Nature, show that it’s possible for planets orbiting M dwarf stars, which are much smaller and cooler than the sun, to be without atmospheres — this was, in fact, the first actual discovery of such a situation. The stars are known for emitting intense ultraviolet light, which can make for less-hospitable solar systems.

“One thing about small M dwarf stars is that they’re very bright in the ultraviolet for the first billion years of their lives, so there are a lot of outstanding questions about whether Earth-size planets around these stars can hold onto their atmospheres,” Kreidberg said. “There are several theories that predict atmospheric loss, but it’s never been observed until now.”

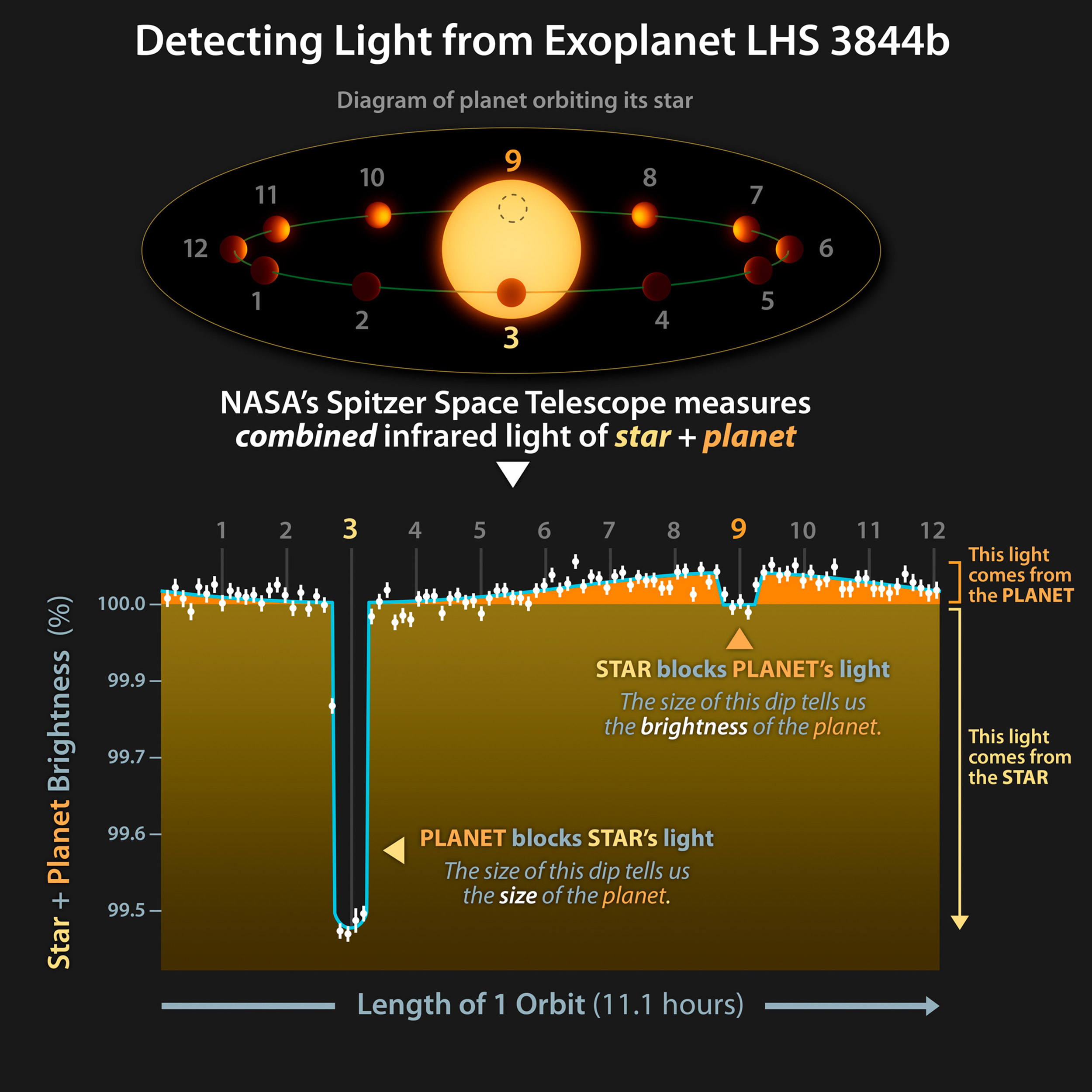

Researchers used a novel technique to determine that planet LHS 3844b has no atmosphere. They measured one side of its climate and compared it to the other to look for a maximum temperature difference. The planet, which is on an 11-hour orbit, is tidally locked, meaning one side always faces the star and the other is always in the dark. A planet with an atmosphere would move some of the heat it absorbs from the hot side to the cold. Using data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, the researchers determined that wasn’t the case with LHS 3844b. They found the side facing the star was heated at more than 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit, while the dark side was consistent with absolute zero.

“We’re pretty convinced that this thing is a bare rock,” Kreidberg said.

The measurement is called the planet’s “thermal phase curve.” It’s the first time this technique was used for a terrestrial planet.

LHS 3844b is 30 percent bigger than Earth. Liquid water cannot exist on its surface and Kreidberg’s team believes the planet’s surface is made of basalt, a very dark rock that can form from cooled lava, similar to the maria on the moon.

Working with Kreidberg on the paper were researchers from Harvard, the California Institute of Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, University of Maryland, University of Texas at Austin, Vanderbilt University, and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Satellite Survey (TESS), which discovered the planet in 2018.