From Mass. Ave. to ‘Sesame Street’

In 2017, Joe Blatt was honored with a Muppet in his likeness. Both professor and muppet spoke with the Gazette about “Sesame Street’s” 50th anniversary and Harvard’s role in the development of the show through the years.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

50 years ago the pioneering show launched with a nudge from the Ed School

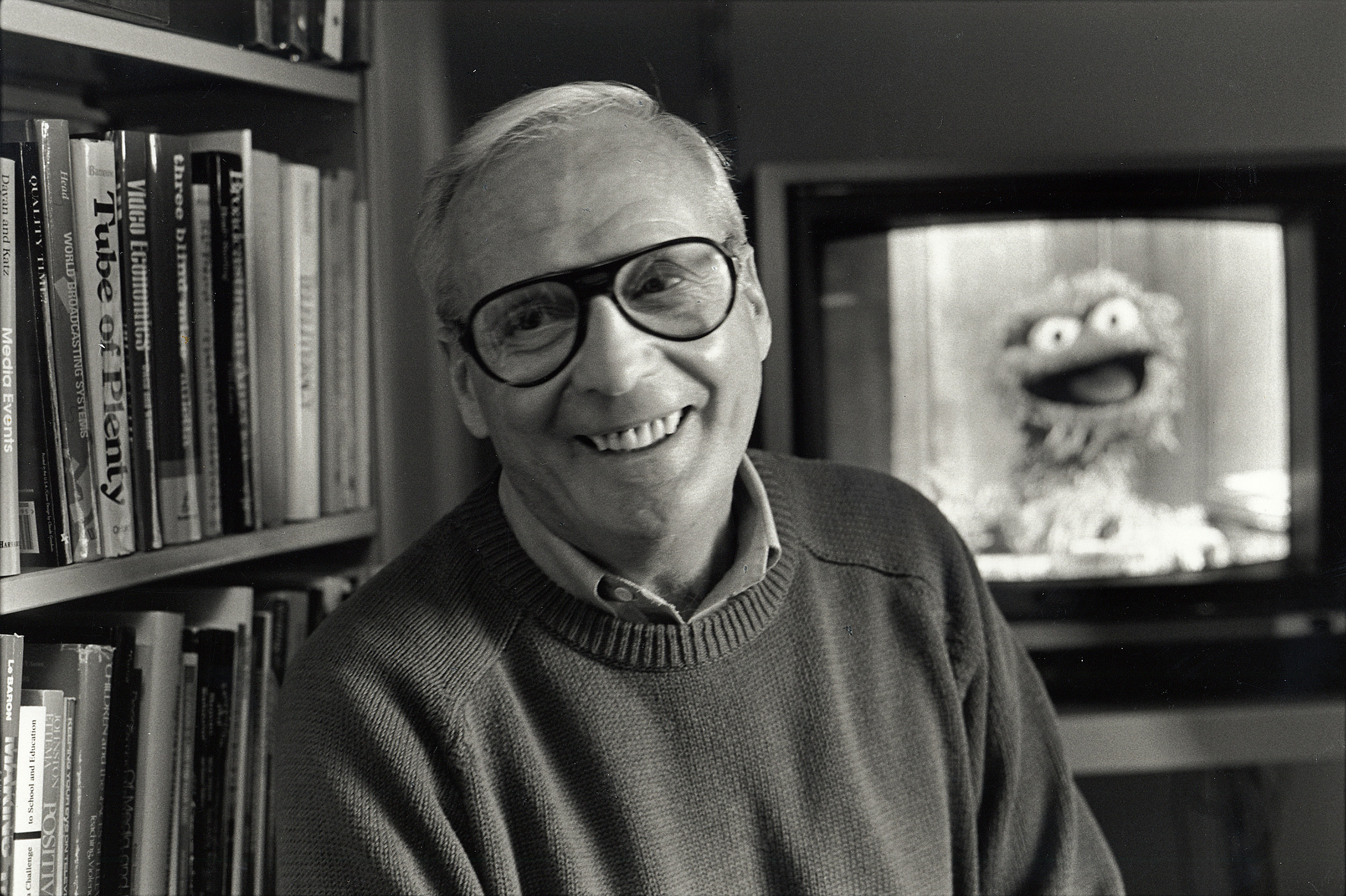

“Sesame Street,” the PBS show that revolutionized educational TV programming for children, turns 50 this year. Big Bird, Elmo, Kermit, Grover, and other beloved furry creatures taught generations of preschoolers that learning about numbers, letters, shapes, colors, and getting ready to read could be fun. But who taught the teachers? Harvard psychologist Gerald Lesser of the Harvard Graduate School of Education was one. From 1968 through 1996, Lesser chaired the board of advisers of the Children’s Television Workshop, which created “Sesame Street.” He developed the curriculum to ensure that the content would be age-appropriate, pedagogically sound, and capable of inducing a smile.

The partnership between Harvard and the show has continued over the decades. Joe Blatt, faculty director of the Master’s Program in Technology, Innovation and Education, leads the many collaborations between Harvard and the children’s show. The Gazette recently sat down with Blatt to talk about the show, Lesser, and, of course, his favorite Muppets.

Q&A

Joe Blatt

GAZETTE: What was the social context in which the partnership between the Ed School and “Sesame Street” emerged?

BLATT: When “Sesame Street” was being planned in the late 1960s, the country was in turmoil; the Vietnam War was really at its height, but these were the Lyndon Johnson years, and there was also the idea of the Great Society, trying to make society more equitable and the country more inclusive. The launching of Head Start was a signal that the government wanted to intervene in education to give more kids a fair start in their learning. That seemed like a natural place for “Sesame Street” to emerge. But in fact, there was a lot of opposition. People thought, “We shouldn’t have people from outside telling us what our kids should learn” because the tradition of education in the United States is that it’s a local matter. Secondly, many countries have a national education curriculum, but the United States has always resisted that. Third, there were many people who thought that preschoolers were just too young to be focused on learning, and they should just have fun. And then finally, when “Sesame” emerged, as well as Head Start, they were racially integrated in a way that was really progressive and very unusual for the time. That sparked a lot of opposition, especially in the South, and in many parts of the country. In that social context, the fact that within the first year “Sesame Street” was a national sensation is really a wonderful story of the possibilities of something good happening in a turbulent time.

GAZETTE: How did the Ed School become involved with the show?

BLATT: The people who had the idea for what became “Sesame Street” were Joan Ganz Cooney, a television producer, and Lloyd Morrisett, a foundation executive. Among their first steps was to recruit Professor Gerald Lesser from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. A number of Lesser’s colleagues told him not to get involved in something as unscholarly as television, but Lesser appreciated the possibilities for children’s learning in this relatively new medium. And he contributed three key things to the success of “Sesame.” First, he insisted that it be curriculum-based to be different from other shows that had some good intentions for children but were just sort of general entertainment. And he arrived at that curriculum by convening a series of seminars in the summer of 1968 that brought together psychologists, sociologists, teachers, as well as television producers, children’s book authors, and entertainment executives. And he did something even more extraordinary because when you get experts together, they usually don’t actually talk to each other; they’re out to impress one another, or they use jargon that other people can’t understand. Gerry, who was the chairman of the board of advisers of Sesame Street from 1968 through 1996, actually succeeded in making television producers, writers, and child experts communicate effectively. And the result was a very detailed curriculum with educational goals.

HGSE’s long relationship with “Sesame Street” began with Professor Gerald Lesser, pictured here in 1994.

Photo by Susie Fitzhugh

GAZETTE: Can you talk about some other ways that Lesser was involved in developing “Sesame Street”?

BLATT: Gerry also mandated an idea called formative evaluation, which means that everything that was going to be broadcast was tested first with children. That way, “Sesame” learned what worked and what didn’t, what was effective and appealing, what children understood but also what they enjoyed. Ideas for segments for “Sesame” had to survive that kind of testing to actually get on the air. And the last contribution by Lesser is the idea that curriculum development, evaluation, and high-quality production would all be permanent parts of what was then called the Children’s Television Workshop. All who took part in it learned to appreciate what one another contributed to the product, and how to actually work together and collaborate. I think that is part of the magic of “Sesame Street.”

GAZETTE: Why do you think the show is still so successful?

BLATT: The big reason for the continuing success of “Sesame Street” is what’s called the “Sesame” model. It is often represented in overlapping circles in a Venn diagram as this continuing collaboration of curriculum, evaluation, research, and production. But it’s also important to know that because that model has proven so successful, around the world every group that wants to make successful learning media for children studies that model and either imitates it or at least tries to learn from it. This is one of “Sesame’s” enduring contributions to the field of learning media for children.

“We try to lift the whole industry through propagating the values that ‘Sesame’ represents: of inclusion, of taking kids seriously, and of using the medium as effectively as possible.”

GAZETTE: And what are “Sesame Street’s” contributions to children’s early education and literacy?

BLATT: “Sesame Street” has had a deep and lasting impact on children’s literacy and numeracy. This is backed up by thousands of studies — “Sesame Street” is the most heavily researched education intervention ever. But what I find especially fascinating is that the curriculum grows every year in response to perceived needs, as identified by experts in education and psychology. In recent years, for example, there’s been a lot of attention on what we call executive function, self-regulation, persistence, delayed gratification, which are things that allow children to succeed. Also, “Sesame” takes both children and the things that matter to children seriously. An example is when the actor who played Mr. Hooper, a longtime character on the show, died, the show acknowledged it and talked about death in a full episode. A more recent example was a wonderful segment, where shortly after Hurricane Katrina, Big Bird’s nest was destroyed by a storm. And Big Bird is looking at it very sad, and one of the human characters says, “It’s OK, Big Bird. It’ll be all right.” And Big Bird says, “It’s not all right.” And the human says, “You’re right, Big Bird. It’s not all right.” That kind of acknowledgement of what kids are really experiencing, rather than just sugarcoating, is part of “Sesame’s” success.

GAZETTE: Lesser said “Sesame Street” was an ambitious social experiment, but it’s been 50 years since it launched. Is it still relevant?

BLATT: In some ways, I feel like “Sesame” is possibly even more relevant than ever. And that has to do first of all with the continuing development of the curriculum. Treating things like executive function that we now realize are fundamental to children’s success is going beyond the original literacy and numeracy idea. “Sesame” has also always experimented: It tackled diversity and inclusion; it had the first African American couple, Gordon and Susan, to host an American television series. But it didn’t stop there. It also introduced Maria, a Spanish-speaking Latina character, and brought Spanish language into the show, and then brought in the Muppet Rosita. Subsequently, there was a lot of attention to disability, and more recently, a great example is the inclusion of autism with Julia, an autistic Muppet character. And finally, the show is still relevant because of its international scope. “Sesame” has been on in more than 150 countries with co-productions that reflect the distinctive children’s needs of each local country. “Sesame” has always had a global point of view, for decades before we began to realize that we all need to have a global point of view. The tradition of both experimentation and social relevance that goes even deeper than the core curriculum continues to be true for “Sesame.”

Q&A with Muppet Blatt

Since 2005, Joe Blatt has taught a course on informal learning for children, which represents the latest phase of collaboration between Sesame Workshop and the Ed School. To thank Blatt for his work directing the partnership, in the summer of 2017 students gave him a Muppet in his likeness developed by Sesame Workshop and the Jim Henson Co. The Gazette sat down for a chat with Muppet Blatt to get his take on life at Harvard, as a Muppet, and with his namesake. GAZETTE: What’s it like being a Muppet at Harvard? MUPPET BLATT: Very educational, and I imagine the classes are great, too. GAZETTE: Do you ever get confused for Professor Blatt? MUPPET BLATT: He does fine getting confused without my help. GAZETTE: Who’s your favorite Muppet? MUPPET BLATT: Well, the truth is that I’m waiting for a call from the producers because I’d love to be in the cast [laughs]. GAZETTE: Why would you like to be in “Sesame Street”? MUPPET BLATT: When you’re as bald as I am, fur looks mighty nice. GAZETTE: If you were invited to join the cast, what role would you like to play? MUPPET BLATT: I’d be a professor, teaching all the major majors. GAZETTE: Will you be your favorite Muppet if you make it to “Sesame Street”? MUPPET BLATT: Exactly. And let me repeat — I’m waiting by the phone.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: Did you grow up watching “Sesame Street”?

BLATT: Unfortunately, I’m too old. But I will say that when I was a student here at the Ed School, I was a student in Professor Lesser’s courses. I always was the one who laughed the loudest and longest whenever he showed clips from “Sesame Street.” I have some “Sesame Street” cred, even though I was too old to see it as a preschooler.

GAZETTE: After Lesser retired in 1998, how did the partnership between the Ed School and the show evolve?

BLATT: I had come to HGSE to learn more about how to make television a more effective learning vehicle. When Lesser was getting ready for retirement, he recruited me to come back and take on children’s educational media. I developed a course called “Informal Learning for Children,” building “Sesame’s” participation in it from the beginning. It wouldn’t just be theory of how to imagine, research, and develop successful educational-media products, but it would have real expertise from “Sesame” and others. The course was the beginning of this latest phase of collaboration between Sesame Workshop and the Ed School. When we announced it in 2005, Grover, the Muppet, came to the School wearing a mortarboard [laughs]. We organized a press conference for him, and he said that of all the major majors, he thought children’s media was the most important one.

Grover visits the Ed School in 2005.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

GAZETTE: What other collaborations between the School and Sesame Workshop are ongoing?

BLATT: Some years, I teach a course in which graduate students get to work directly with Sesame Workshop executives, helping them to explore ideas for potential development. We also have had a number of graduates go to work at Sesame Workshop and at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, which is “Sesame’s” research arm. And a lot of our graduates go into careers in educational media and technology beyond “Sesame.” We try to lift the whole industry through propagating the values that “Sesame” represents: of inclusion, of taking kids seriously, and of using the medium as effectively as possible.

After Lesser, the work of Harvard faculty with Sesame Workshop has continued. In the early years, Courtney Cazden and Jeanne Chall, both reading experts, contributed to “Sesame’s” literacy curriculum, and especially to launching a program called “The Electric Company,” which for many years was a popular way for kids to get introduced to reading. More recently, Catherine Snow has contributed to “Sesame” on how to integrate Spanish and multiculturalism into the program. And then up to the present, a major focus of “Sesame’s” curriculum has been executive function, which is the idea that children need certain habits of mind to be successful. Much of that was inspired by the research of our colleague Stephanie Jones, who has worked with “Sesame” to help them learn about it and then implement it.

Our faculty, thanks in part to Lesser’s leadership, have been willing not only to supply research and expertise, but actually to join with writers and producers to make those ideas into effective programming. Here at HGSE, all of us share core commitments, including making learning accessible and appealing to all children, regardless of any differences among them, and realizing that giving kids a good first step into learning has critical implications for their whole lifelong success. And we all believe that education is perhaps the best lever for accomplishing social justice and overcoming the growing inequality in our society.

GAZETTE: To wrap up the interview, let me ask you a personal question: What is your favorite Muppet?

BLATT: I find all the Muppets so funny, fuzzy, and lovable that it’s really hard to choose. But I will confess to a weakness for blue fur [laughs].

GAZETTE: So that means it’s either Grover and Cookie Monster or both?

BLATT: Both, but you’re putting monsters in my mouth [laughs]. I ended with the blue fur.

“Sesame at 50: Celebrating 50 Years of Sesame Street” will be held Wednesday at 4:30 pm at Sanders Theatre. The program is not intended for children and is for Harvard ID holders only. Admission is free, but tickets are required. Tickets are available at the Harvard Box Office.