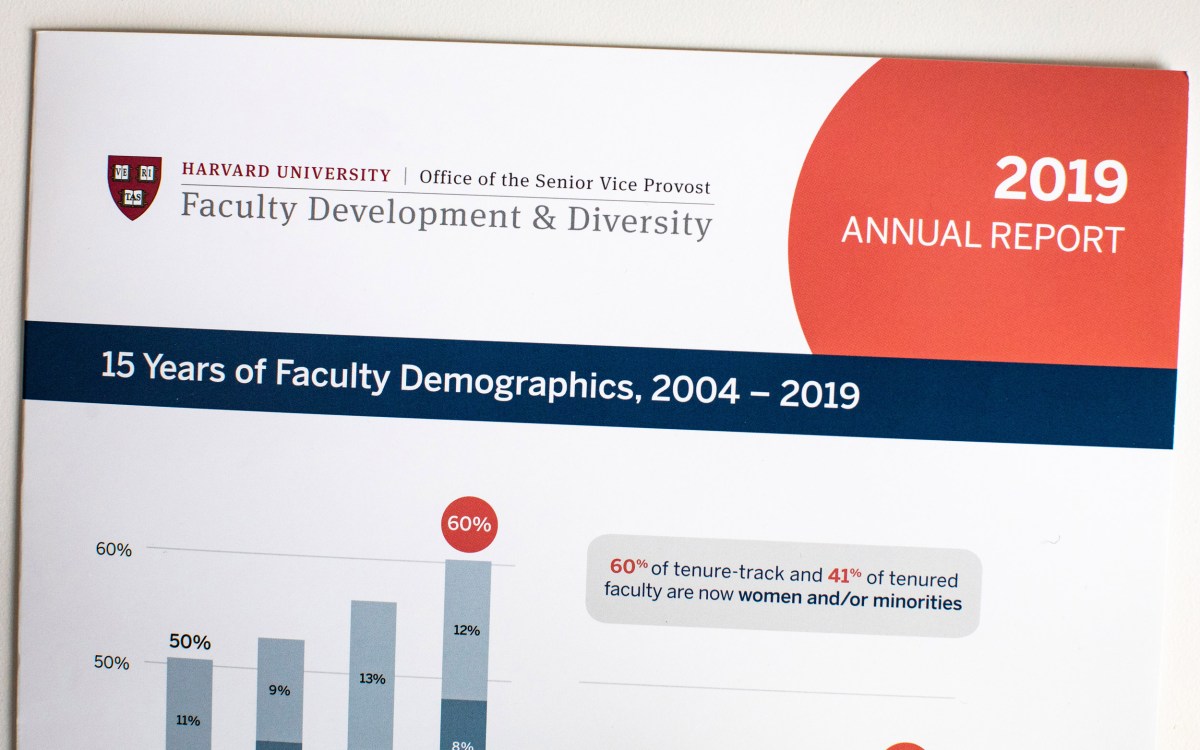

Vinothan Manoharan (left) and GSAS student LaNell Williams work in the Manoharan Lab.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

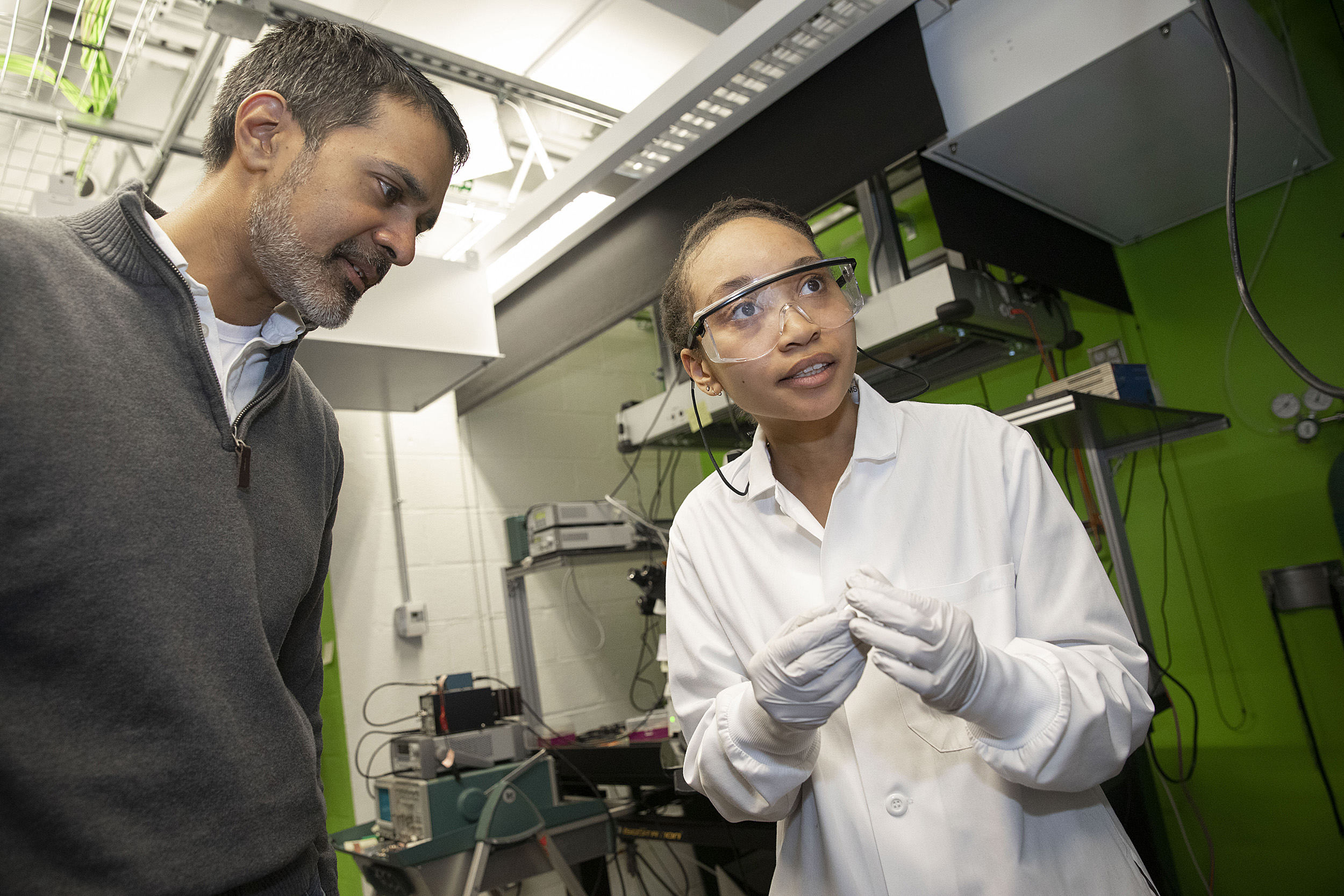

Unhidden figures

Conference encourages women of color to pursue doctorates in physics

If there’s one thing LaNell Williams wants women of color interested in studying physics at top institutions to know, it’s this: You can do this.

Williams is a Ph.D. student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences working in the lab of Wagner Family Professor of Chemical Engineering and Professor of Physics Vinothan Manoharan, and just the third African American woman to pursue a doctorate in physics at Harvard. When she graduates she will join a cohort of fewer than 100 African American women who have received doctorates in the field since 1973.

“When I tried to apply to Harvard, despite everything I had — a 3.93 GPA and a National Science Foundation fellowship — I was told I was reaching too high. And if you asked any black woman in this field, especially those of us who are at places like Harvard, they’ll tell you similar stories,” Williams said. “The biggest thing Harvard and places like it miss when it comes to recruiting is that they’re not encouraging those of us who are qualified, those of us who are ready, those of us who are able, to come to these places.”

To help change the situation, Williams co-founded the Women+ of Color Project as a student at Wesleyan University to support women of color in STEM fields. The group ran a three-day workshop at Harvard recently for 20 African American, Latinx, and Native American women interested in pursuing a career in physics, astronomy, and related fields. Attendees were selected from a pool of candidates who had applied or been nominated, and the goal of the event was to help them access the resources they need to apply to and succeed in graduate school.

“I’m bringing these students here now, because I want to tell them, ‘You are good enough,’” she said. “They have the grades; they have the scores; they have the pedigree. What’s keeping them from applying — and this is what I’m focused on — is the conversations and the resources.”

In her keynote speech, Nia Imara, a John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, urged the women to bring their unique perspectives to the fields they study.

Participants shared their stories and experiences in academia.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“I don’t love the fact that women and minorities are underrepresented in science, because I know we have knowledge to contribute just like everyone else,” said Imara, who studies how stars are born in the Milky Way and other galaxies. “When I go to a conference and I look out in the audience, I can’t help but notice who is missing, and I can’t help but think this is a loss for the scientific community.

“Most of you are forging a new path, and that takes courage,” she continued. “I know it hasn’t been easy. As a female student and a female student of color, you have had to face obstacles others haven’t. You may have been discouraged or excluded, and I know that often you’ve never been properly acknowledged or apologized to. But not in spite of, but because of your experiences, you have a unique way of seeing the world. You have a unique set of qualities that will make you an asset whether you decide to go to grad school or otherwise.”

As part of a session designed to walk students through the process of applying to graduate school, Director of Graduate Studies for FAS Science and Co-Director of Graduate Studies for Physics Jacob Barandes shared tips on what admissions committees look for in students.

Jacob Barandes dispensed advice on applying to graduate school.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“If you’re here, it’s probably because you love learning,” he said. “So apply. Please don’t count yourself out. You may have heard from people that you’re not strong enough. Forget about that. You are much stronger than you think you are, so please apply, and let the admission committees decide.”

Other workshop events included deep dives into how to write a graduate school essay, feedback from Harvard physics faculty and postdocs, lab tours, information on fee waivers, and helping students work on their applications to Harvard. The workshop was generously funded by the Heising Simons Foundation.

The students also had the chance to attend events with faculty and get to know other women in the program during dinner and a movie.

For students like Tracy Edwards, who came to the workshop from Hampton University in Virginia, the realization that she was part of a community of like-minded women who wanted to study physics was invaluable.

“It’s like a drink of water,” she said of seeing the other women attending the conference. “When you’re really parched, you’re in a desert and have no water and are just desperate. And I come here and I can say, ‘You look like me. You have the same experience as me.’ It’s like a drink of water.”

Volunteer Juliana Garcia-Mejia (left) from GSAS shares a laugh with LaNell Williams during the workshop.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Like many of the students who attended the workshop, Edwards had repeatedly been told she didn’t belong.

“I saw an ad for this program on Facebook. It was 10 p.m., and I’d spent eight hours working on the application,” she said. “I thought there was no way I would get invited, but I just needed something to hope for, because I felt like no matter what I did I wasn’t going to get anywhere.”

That belief, she said, stemmed from a long history of dispiriting conversations with faculty that “destroyed” her confidence.

“This past summer, I took a math class, and the professor told me that the only reason I would get into grad school was because I’m black — that I was just a racial quota,” she said. “After one test that I didn’t do very well on, I emailed him to ask what I could do to improve, and he emailed me back and said, ‘You’re not worth my time.’ And that hurts, having a teacher who is supposed to help you and teach you and guide you say you’re not worth their time. What do you say to that?”

“When you’re really parched, you’re in a desert and have no water and are just desperate. And I come here and I can say, ‘You look like me. You have the same experience as me.’ It’s like a drink of water.”

Tracy Edwards, Hampton University

For many of the other women attending the conference, stories like Edwards’ are maddeningly familiar.

“The level of discrimination I felt in my first year of physics was horrible,” said Sideena Grace, a junior at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minn. “I was working three jobs, so I did terrible in my physics class, and one of my professors told me last week that they expect me to have the lowest grade in the class because I struggled in [it].

“I just broke down because I’m just tired of explaining myself,” she continued. “The expectation for me is lower, so now I have to work three times harder to prove them wrong.”

And though last week’s conference is a critical step forward in encouraging women of color to follow their passion for physics and apply to programs like Harvard’s, Edwards emphasized institutional change is also necessary.

“As a minority woman, it’s not my job to correct your bad behavior,” she said. “Yes, it’s great for us to be here and break the mold or break the pattern, but it’s also the job of professors and people who are in admissions to acknowledge their own biases and fix them. I shouldn’t be expected to.”