Angela Davis in black and white and gray

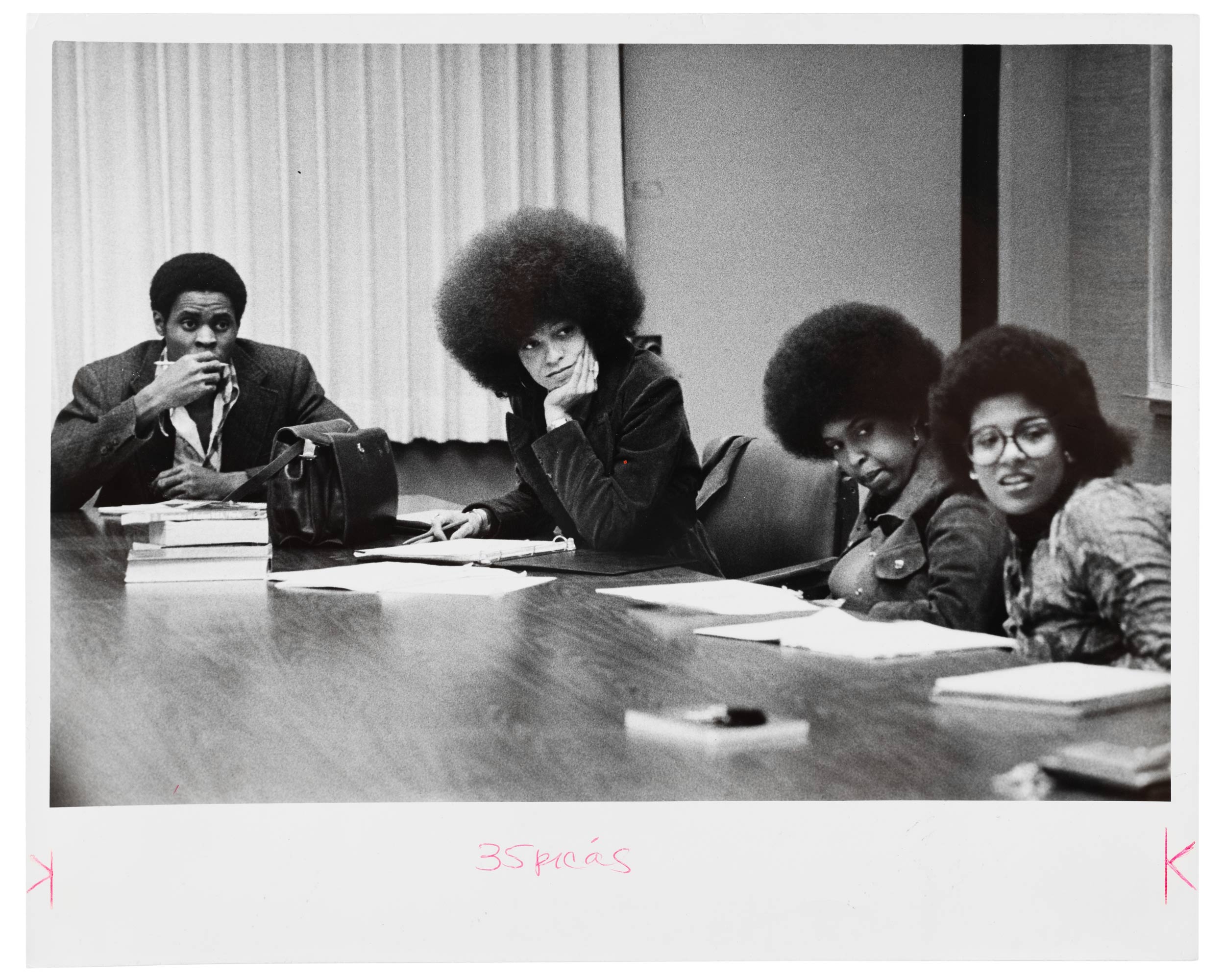

Photo of Angela Davis’ class at Claremont College, 1975.

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

New exhibit, curated from her personal archive, chronicles the life of a complicated activist and scholar

There are two small black-and-white headshots of a young woman with a large afro, one dated 1969, one 1970, topped by these lines:

Wanted by the FBI

Interstate Flight — Murder, Kidnaping [sic]

Angela Yvonne Davis

The infamous poster from 1970 is one of the artifacts on view at “Angela Davis: Freed by the People,” a new exhibition at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Curated from Davis’ archive, the exhibition showcases the complex and storied activist, author, and scholar beyond the headlines that defined her rise to fame as an icon of the Black Power movement in the late 1960s.

“We’re trying to show our visitors the side of Angela Davis that might be more familiar, but also the more personal and intimate side of her,” said Elizabeth Hinton, John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences and associate professor of history and African and African American studies, who organized the exhibition with a committee of Radcliffe specialists. “She is a complicated figure who at a very young age was thrust into a number of struggles, and we also want to set her political commitments in a larger context,” that includes her upbringing and academic work as a feminist philosopher and educator.

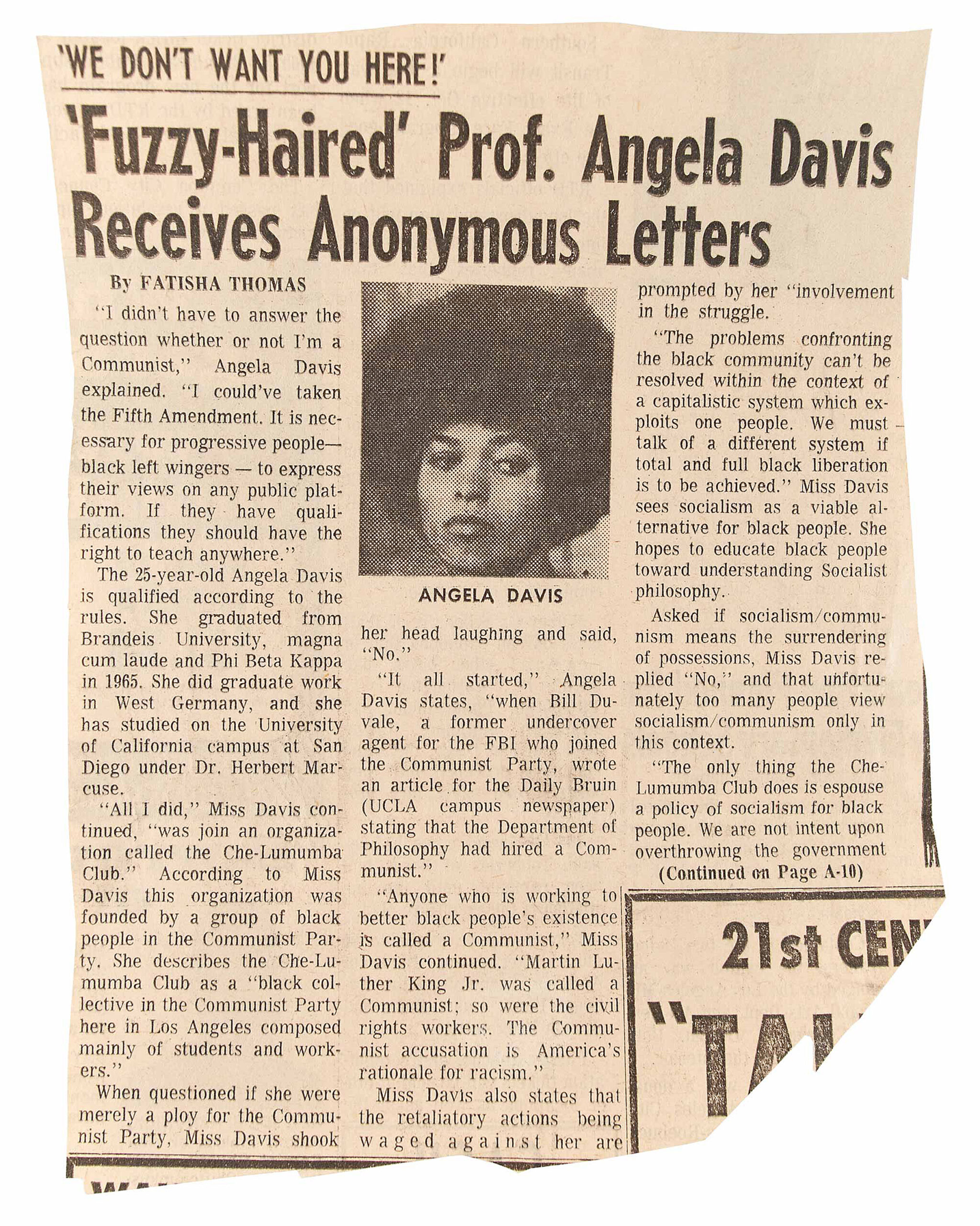

An editorial from the Los Angeles Times, shortly after Davis was fired from UCLA

In the audio clips, curator Elizabeth Hinton puts pieces from the exhibition in context.

transcript

Transcript:

This is a editorial from the Los Angeles Times around the time that Angela Davis’s firing from the philosophy department at UCLA was causing a lot of controversy, and this is particularly interesting, one: because Angela actually kept it.

This is, of course, before the trial, before she becomes this revolutionary global icon. It’s a racialized headline that’s kind of pointing out something about her hairstyle and the ways in which people are conflating her communist politics with her race, and this is kind of the beginning of what was to come during her trial and after, and what, in some circles, the kind of criticism that she faces today.

The exhibition is on display at the Lia and William Poorvu Gallery in the Schlesinger Library, and it includes items from Davis’ early life in Birmingham, Ala.; her arrest and trial over her role in a deadly 1970 prisoner escape from a California courthouse; a world tour of socialist and communist countries that put Davis on the global stage; her extensive catalog of written work; and her contemporary activism on prison abolition and the rights of incarcerated people.

“Equality, freedom, challenging confinement, critiquing the justice system, emphasizing the importance of intersectionality — Angela Davis was always way ahead of the curve,” said Hinton.

Bracelet of Ruchell Magee, the world’s longest-held political prisoner

transcript

Transcript:

This is the bracelet of Ruchell Magee, and it’s actually one of my favourite objects in the Papers of Angela Y. Davis at the Schlesinger. Ruchell Magee is the world’s longest-held political prisoner.

He was one of the only survivors of the Marin County Courthouse Incident where Jonathan Jackson, Ruchell, and others, took a number of people hostage in order to demand that the conditions inside Soledad Prison and in prisons throughout the state of California, be addressed. At one point, Angela Davis and Ruchell Magee were going to be tried together, and it says something that Angela kept Ruchell Magee’s bracelet.

Ruchell Magee is still incarcerated in California and he continues to work to help other people get released. He’s kind of a jailhouse lawyer, and he continues to write and reflect on all kinds of political matters of the day.

Part of what this bracelet shows and the way we displayed it in the exhibit is to include the bracelet and a pamphlet released by one of the many committees working to secure Ruchell Magee’s freedom. I think it’s really important to include in the exhibit because it reflects the kind of continuities between Angela Davis’s trial and our own day.

“One of the exciting things about exhibiting the Angela Davis materials is that it gives visitors to the Poorvu gallery a taste of the kinds of research that they and others will be able to do in the next years and decades and generations,” said Jane Kamensky, Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History at Harvard University and Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe.

At 26 and having been fired as a UCLA philosophy professor due to her radical political activism, Davis became a famous face of the Black Freedom struggle when guns registered in her name were used in a hostage-taking and shootout at the Marin County Courthouse in San Rafael, Calif., that left three suspects and a Superior Court judge dead. She was charged as an accomplice to conspiracy, kidnapping, and homicide. After two months as a fugitive, FBI agents arrested her in New York City. She spent more than a year in prison before being acquitted by an all-white jury in 1972.

Davis remained an active member of the Communist Party of the United States of America until 1991 and ran for vice president twice on the party ticket in the 1980s. In 1997, she co-founded Critical Resistance with Rose Braz, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and other activists to dismantle prison systems. She also taught in the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies programs at UC Santa Cruz for 15 years before retiring as a distinguished professor emerita in 2008.

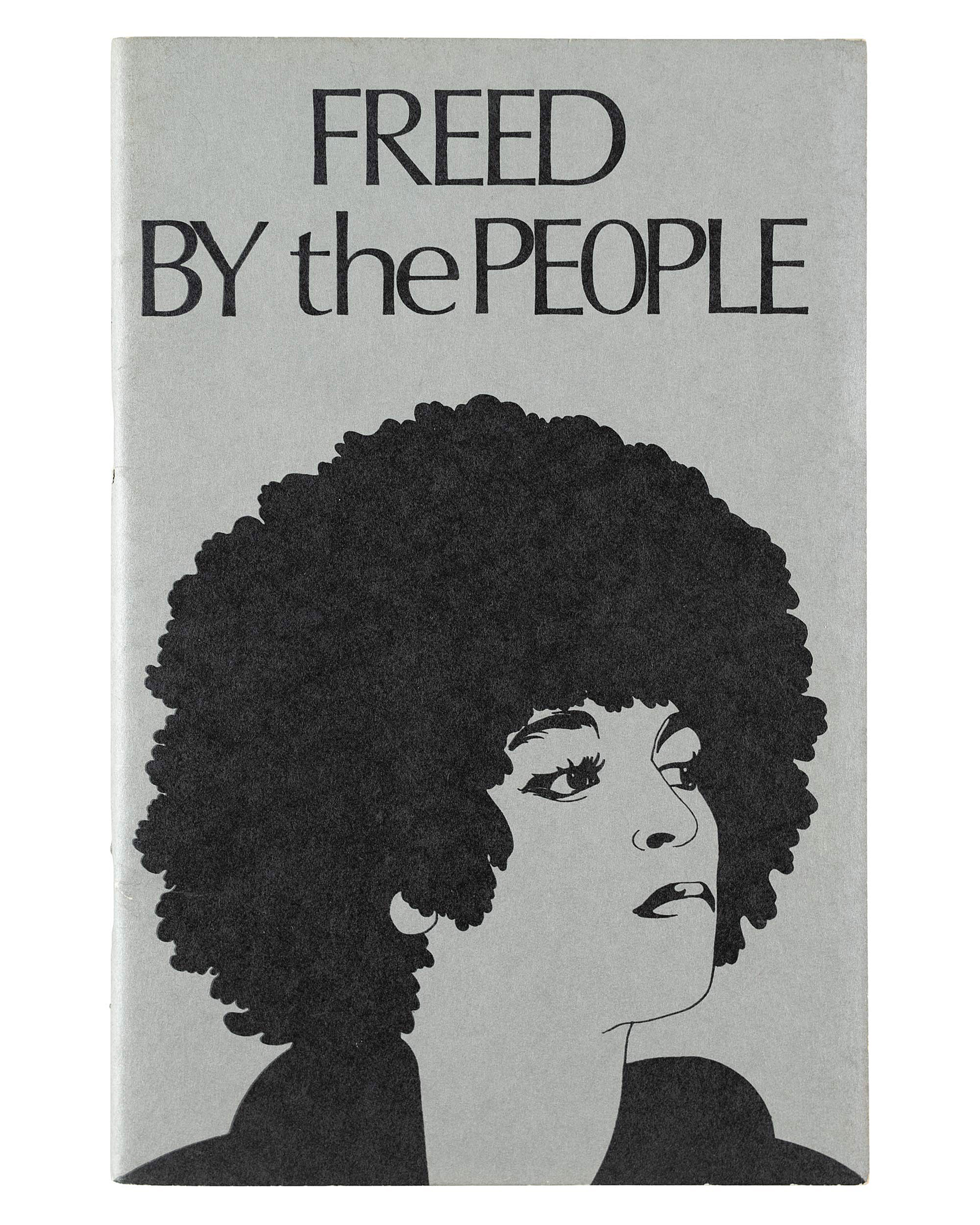

A pamphlet produced by the Free Angela Davis Defense Committee

transcript

Transcript:

This is a pamphlet produced by the Free Angela Davis Defense Committee entitled “Freed by the People,” and it essentially is the text of the closing statement that Angela Davis’s defense team prepared and delivered before the jury on June 1, 1972, and then three days later that same jury — all-white jury — acquitted Angela.

The image of Angela drawn here is particularly striking as well as the idea that she was freed by the people, that it wasn’t just Angela herself and her lawyers that led to her acquittal but it really was this worldwide, mobilized support — tens of thousands of people — that demanded her freedom and who saw her case not just about the case of Angela Davis but about struggles against exploitation and oppression worldwide, that somehow this acquittal signaled the coming liberation of all oppressed people.

The title of the exhibition comes from a pamphlet published by the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis in 1972. The gray booklet, in which is printed the trial’s closing statement by Davis’ lawyer Leo Branton, features an illustrated portrait of Davis. The pamphlet is the lead artifact in the exhibition.

“Davis’ own political commitments and philosophical foresight has made her work and life history translate very clearly to the issues at the center of national and international struggles today,” said Hinton. “We are asking visitors to think about the ways in which these struggles have changed and evolved, and the ways in which they’ve also remained the same.”

“People might come away from the exhibition with an appreciation of Davis’ work, and they might come away from it with hard questions,” said Kamensky. “As a research library, we acquire and preserve these collections to deliver to scholars and other storytellers, and we will find new answers and ask new questions from the materials that are on those walls and in the rich and large collection of the Davis papers.”

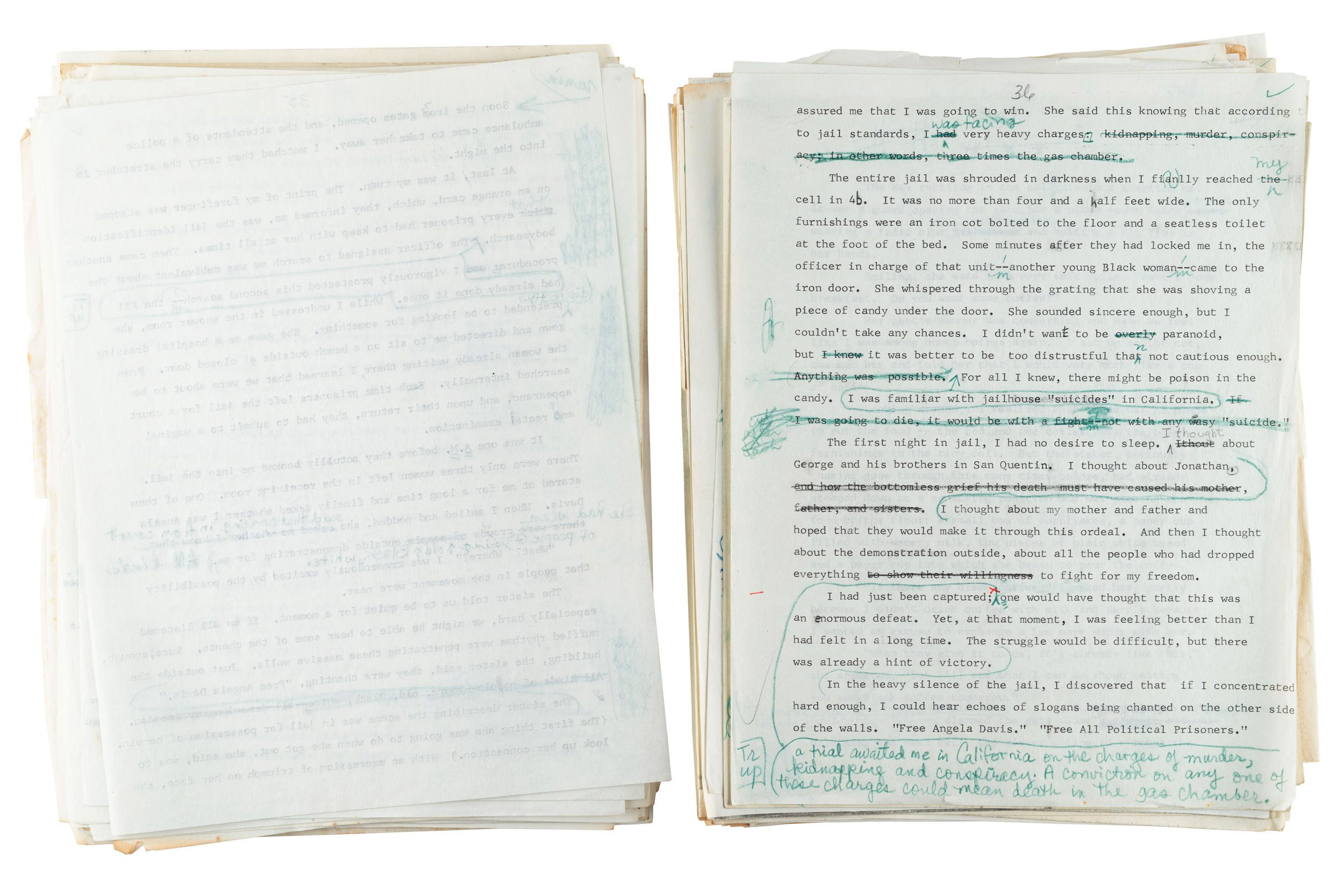

Manuscript of Davis’ autobiography, with edits from author Toni Morrison

transcript

Transcript:

This is Toni Morrison’s line edits of a draft — one of the final drafts — of Angela Davis’s autobiography and at the time, Toni Morrison was an editor at Random House and she also went on to edit Angela’s classic, now-classic text in feminist studies, women’s studies, “Women, Race, and Class.” In these pages, Angela is writing about what it’s like to be incarcerated and we really see the care and detail and love that Toni Morrison put into her editing process, and we get a sense of not only both of their writing processes, but also the relationship between the two women.

In addition to the FBI wanted poster, the exhibition displays personal items like Davis’ prison letters and a manuscript of her 1974 autobiography with handwritten notes from Toni Morrison, then her editor at Random House. The artifacts depict the spectrum of responses people had to Davis, from the international support she received during her months in prison to the hateful messages and negative press coverage about her work and politics.

“Our key criterion is always significance, and there are many ways for materials to answer that question. It could be significant by being incredibly densely documented, or it could belong to a highly placed individual who has made change,” said Kamensky. “The papers of Angela Davis fulfill both of those criteria. The collection is very rich, and she’s been a significant force in American life. So, whatever one thinks of her politics, and I think many people who come to the gallery or research the collections will have varying opinions on that, we hope that always the work of study, of exhibition, of inquiry, and of research in our reading room is to submit our opinions to the hard assay of documentary materials and fact.”

Besides artifacts from Davis’ life, the exhibition also includes material detailing the contemporary work of prison abolitionists and the wide reach of the social justice movements that Davis championed throughout her life.

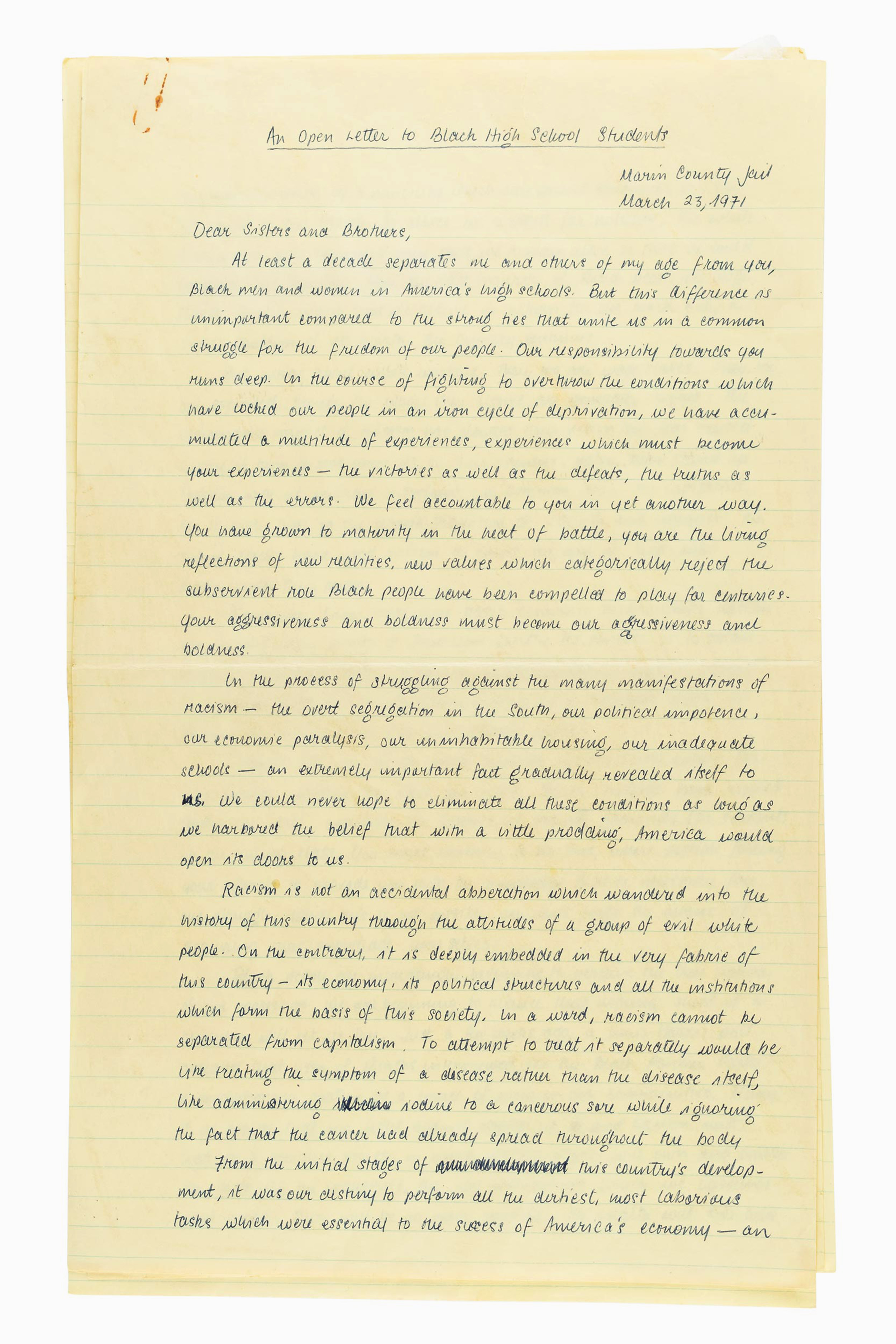

Open letter by Davis to black high school students while she was incarcerated in 1971

transcript

Transcript:

This is an open letter to black high school students that Angela Davis wrote when she was incarcerated in Marin County Jail in the spring of 1971, and this is, of course, a moment when revolution seems really imminent, and in fact the Free Angela Davis movement was, in many respects at least domestically, at the center of a lot of revolutionary activity in the United States. Here, Angela Davis is talking about and theorizing revolution and seeking to inspire the younger generation to rise up and join the movement in something that she sees as logical and inevitable.

This is a real treasure in the archive, in part because it’s written in Angela’s own hand, and it was later published in “The Black Scholar” journal, so it was read by many, many more people.

“We hope that this exhibition is inspiring for people, both to carry on Davis’ good and difficult work, but also to understand more about the holdings of the library,” said Meg Rotzel, arts program manager at Radcliffe, who designed the exhibition with gallery coordinator Joe Zane. “The archive of the Schlesinger Library is open to the public, which is a very unique thing, and we want people to think of this space and its collections as resources for their own work.”

“The aim of the exhibition is to try to use Davis’ life as a starting point to think about larger issues of inequality, and I think that is how Davis always saw herself,” said Hinton. “Even though the jury technically acquitted her [in 1972], it was the global movement that emerged in the context of her trial that the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis and Davis herself would want to emphasize. Her causes were the causes of the people.”

“Angela Davis: Freed by the People” is on view at the Schlesinger Library through March 9, 2020.