Shawon Kinew leads a first-year seminar where students study portraits of indigenous American leaders to learn about art, identity, and the history of indigenous peoples.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Art and the history of indigenous America

First-year seminar focuses on the 19th century oil portraits of 25 Native leaders captured in an era of forced relocation

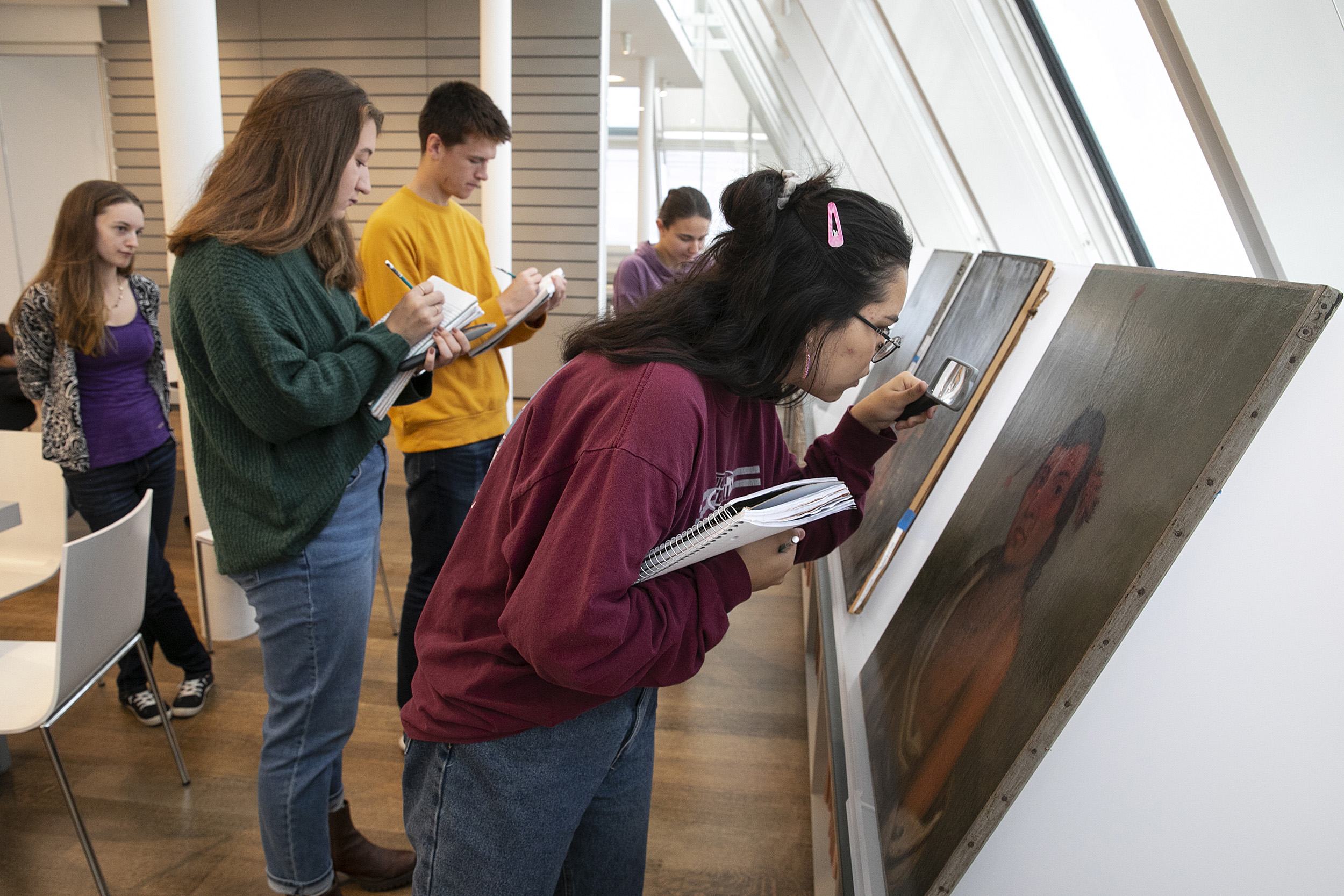

Five first-years gathered around a table in a well-lit study room at Harvard Art Museums on a recent afternoon to examine three oil portraits of indigenous American chiefs attired in ceremonial regalia, with necklaces, exquisite feather headpieces, and blankets.

Using magnifying glasses and portable ultraviolet lamps, the students inspected the early 19th-century images of Bayezhig (Lone Man), a Snake River Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) leader; Mizhakwad (Clear Sky), an Ojibwe chief from Rainy Lake; and Tahcoloquoit (Rising Cloud), a warrior of the Sauk nation (Othâkîwa).

It was a special session on art research and preservation, but as students have come to expect, the most important lessons offered by the course “The First Americans: Portraits of Indigenous Diplomacy and Power” involve more than conservation, or even art history.

The first-year seminar centers around the paintings of 25 Native leaders and chiefs painted by Henry Inman, a noted portraitist of his time. It focuses on critical thinking and research skills and the interplay of art, identity, and representation. It also explores the history of the peoples who inhabited the land long before it became the United States, through images that capture their strength and resilience even as they are being targeted by aggressive land-removal policies.

For Shawon Kinew, assistant professor of history of art and architecture and Shutzer Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, the class gives students a chance to have “a conversation with the past” and get acquainted with a part of U.S. history that is often overlooked.

“The takeaway is that the past still needs to be interpreted in many ways,” said Kinew, an art historian who received her Ph.D. from Harvard in 2016. “But also, that the people who are represented in these paintings didn’t become extinct. Their descendants are still here, and their nations are still here. Their languages are still spoken; the things they’re wearing are still worn and used in ceremony today. There’s something very powerful about the paintings and the sitters because they transcend what was once described as a moribund history.”

The complexities of Native American history come as a revelation to many students.

“I learned that indigenous history is American history and shouldn’t be treated as a side unit, the way it is taught in school,” said Maddy Ranalli ’23. “We also talked about colonization and the many pervasive ways in which it still continues to operate. I usually walk out of every class and I’m like, ‘Wow, wow, wow.’”

Finding their home in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, the Inman paintings are copies of the original portraits painted by Charles Bird King. Thomas McKenney, who ran the Bureau of Indian Affairs between 1824 and 1830, hired King to paint the Native leaders who traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate treaties with the U.S. government. Since most of King’s portraits were destroyed in a fire that consumed the Smithsonian Institute in 1865, Inman’s canvases are among the few records that capture the Native American leaders of that era.

Because of their historical value, the paintings, some of which have experienced invasive treatment, are the focus of a conservation initiative to protect them from future damage and deterioration, a joint effort by the Peabody Museum and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies.

Associate paintings conservator Cristina Morilla and Julie Wertz, Beal Family Postgraduate Fellow in Conservation Science, who are part of a multidisciplinary team working on the conservation of the Inman paintings, recently spoke to the class about the conservation project.

“It’s very important for the Peabody Museum to preserve the surviving portraits of these prominent leaders and chiefs,” said Morilla, who encountered the Inman paintings as she was doing a survey of the Peabody collection. “I was astonished by the amazing quality of the paintings, and also because they’re very unusual. These portraits depict Native American leaders with all their regalia and the power they held as representatives of their tribal nations during their negotiations with the U.S. government.”

“There’s something very powerful about the paintings and the sitters because they transcend what was once described as a moribund history.”

Shawon Kinew, assistant professor of history of art and architecture

As part of the class, students have to write a visual analysis based on an hourlong observation of one of the paintings. It’s a challenging task, said Kinew, because students have to go beyond the first impressions of seeing the leaders as “oppressed people” and gain access to the traditional knowledge embedded in the paintings through the cultural items the sitters bear.

“These leaders and chiefs were engaging in nation-to-nation negotiations, and were wearing ceremonial regalia and sacred objects, which reveal the power they have, not only as political diplomats, but in some occasions also as spiritual leaders,” said Kinew.

The course attracted Emerald GoingSnake ’23, who is Cherokee and Mvskoke (Creek) because she wanted to learn about her Mvskoke heritage, and also because it was taught by Kinew, who is a member of the Ojibways of Onigaming First Nation in Canada.

“It is important that Native professors are teaching about Native issues,” said GoingSnake. “I believed this course would make me feel seen, recognized, and it has, but the most powerful part of the course is to learn how decolonization ties into our discussions of these paintings and the larger notion of history. We are learning how the inclusion of Native voices changes our perspective of how history is told.”

For Henry Austin ’23, who is part Choctaw but did not grow up with Choctaw traditions, Kinew’s class has given him the opportunity to “connect with his ancestors” and learn “much more about the beauty of indigenous art, traditions, and resistance.”

“I’ve never had the opportunity to interact with objects like those in the Peabody Museum, and it has been interesting to analyze objects as part of a greater narrative,” said Austin. “Indigenous perspectives are fundamental to changing any narrative in this country, and that is something I have had the chance to learn from this class.”

As part of the course, there will be two special public lectures on Anishinaabe language and art in honor of the U.N. International Year of Indigenous Languages. Alan Ojiig Corbiere of the Great Lakes Research Alliance for the Study of Aboriginal Arts and Cultures will give the lecture “Listening for Grandfathers: Aadizookaanag in Museum Collections” on Thursday at 6 p.m. at Sackler 422, 485 Broadway, Cambridge. Anton Treuer, professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University, will deliver “Ojibwe Language Warriors in Action: Connecting the Academy, the Community, and the Quest for Knowledge” at Sackler Lecture Hall on Nov. 20 at 6 p.m.