Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Spatial awareness

“What you see in the built environment didn’t fall from the sky; [it’s] a product of decisions people made. It’s not natural, and it’s not inevitable.”

Daniel D’Oca, M.U.P ’02, his work focuses on the ways social inequities are reflected in the planning and building of communities, inequities that are perhaps most readily apparent when it comes to race.

“I used to teach in Baltimore,” said the associate professor of urban planning. “I worked on an exhibition with my students about different artifacts and policies of segregation, and we used the city to study how segregation happens. People would always say, ‘You think Baltimore is an interesting case study, you should look at St. Louis.’”

That city, like Baltimore, has a long history of stark inequality and physical division bolstered by practices such as racially driven zoning laws and the refusal by lenders to approve mortgages in African American neighborhoods, making it harder for those residents to own property and adding to the racial wealth gap.

Creating those kinds of separations has far-reaching impacts that go beyond housing, affecting education, crime rates, upward mobility, and even life expectancy.

“There’s something called the Delmar Divide in St. Louis,” D’Oca said, explaining, “It’s a line that really does separate white and Black, but it also divides income levels, the condition of houses, and the levels of vacancy. There’s a 20-year life expectancy difference between some of St. Louis’ highest median income ZIP codes and lowest median income ZIP codes.”

In 2015 D’Oca created a studio course that expanded on the work of a nonprofit that was improving U.S. streets named after Martin Luther King Jr. The class walked St. Louis’ street and met with residents, business owners, and community development groups to better understand what improvements they wanted and what the barriers to achieving those were. The class then delivered practical solutions that the community could continue after the class ended.

The next year, D’Oca widened his scope to the whole city with his course “Affirmatively Further: Fair Housing After Ferguson,” inspired by both the racial schisms that Michael Brown’s death exposed and an often unenforced section of the Fair Housing Act.

“[The section says] you can’t just have all wealthy people, or all white people, living in a neighborhood,” D’Oca said. “You have to show that you have opportunities for low-income people to live in your community.”

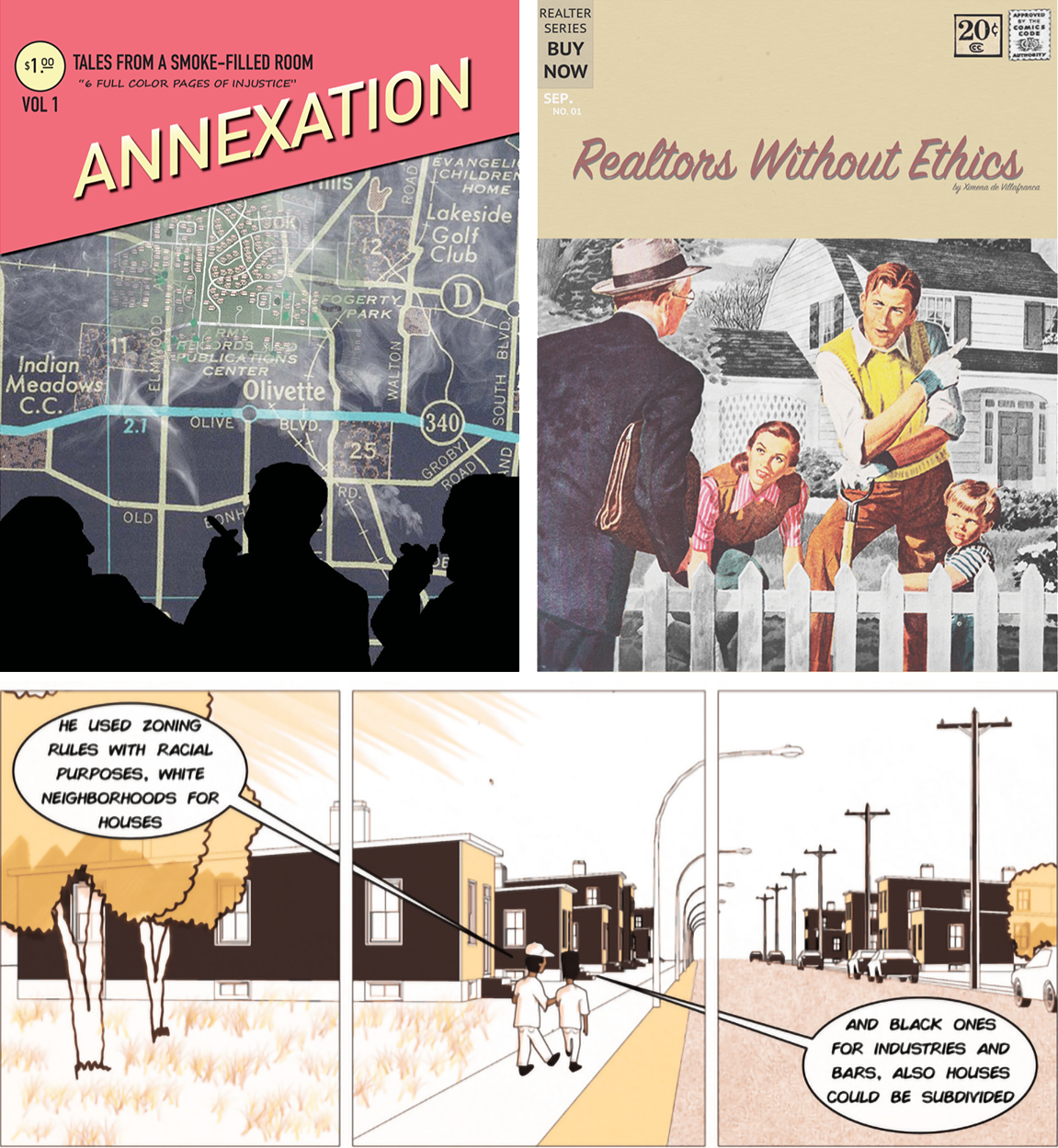

Examples of some of the comics that students from D’Oca’s “Affirmatively Further” studio created to more easily explain the city’s history of inequality.

Comics by (clockwise) Jake Watters, Ximena de Villafranca, and Ruben Segovia

A collage of all the people that D’Oca’s studio course met on Dr. Martin Luther King Dr. in St. Louis.

Photo courtesy of Dan D’Oca

Similar to the previous course, D’Oca’s students started by meeting with different segments of the city, discussing their needs, brainstorming solutions, and then implementing the best ones.

For a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, one student dug through local zoning laws and found that a good portion of African American homeowners could build a type of in-law suite called an “accessory dwelling unit” on their property, which they could then rent to newcomers, benefiting landlord, tenant, and community diversity.

Two other students were inspired by a resident who pointed out that part of the reason for ongoing inequality was a lack of knowledge about how it happens. The students decided to create a book for fifth-graders explaining that segregation in the city came about because of a series of choices. The book’s approach took readers through decisions about the design of their rooms and how such design decisions affected their lives (e.g., making your door a certain width allows for passage of some things and not others) and then expanded the concept to the house, the neighborhood, the city, and the region.

After that course, D’Oca and a group of students teamed up with the Commonwealth Project to work long term with Ward 3, a neighborhood in St. Louis that is 94 percent African American and has some of the highest rates of poverty in the city, coupled with the lowest home values and life expectancy rates.

“One of the things that we did for the studio [course] was decide to make a newspaper that has all these interesting tidbits about the neighborhood and about local leaders.” The publication also includes articles about how to benefit from government-funded home repairs and how to maintain or buy vacant lots.

“St. Louis is fortunate in a way,” D’Oca said about the future of the city. “The young people will come to St. Louis. People of all races are going to decide that city living is for them. I don’t want to say it’s inevitable, but it’s likely, and I think that if St. Louis is smart it can get ahead of this issue and start to ensure that this development benefits people who are there now, but it requires time, money, and planning. It requires strong leadership.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.