An algorithm to help predict Alzheimer’s

Christian Langballe/Unsplash

Team works to detect disease early using electronic health records

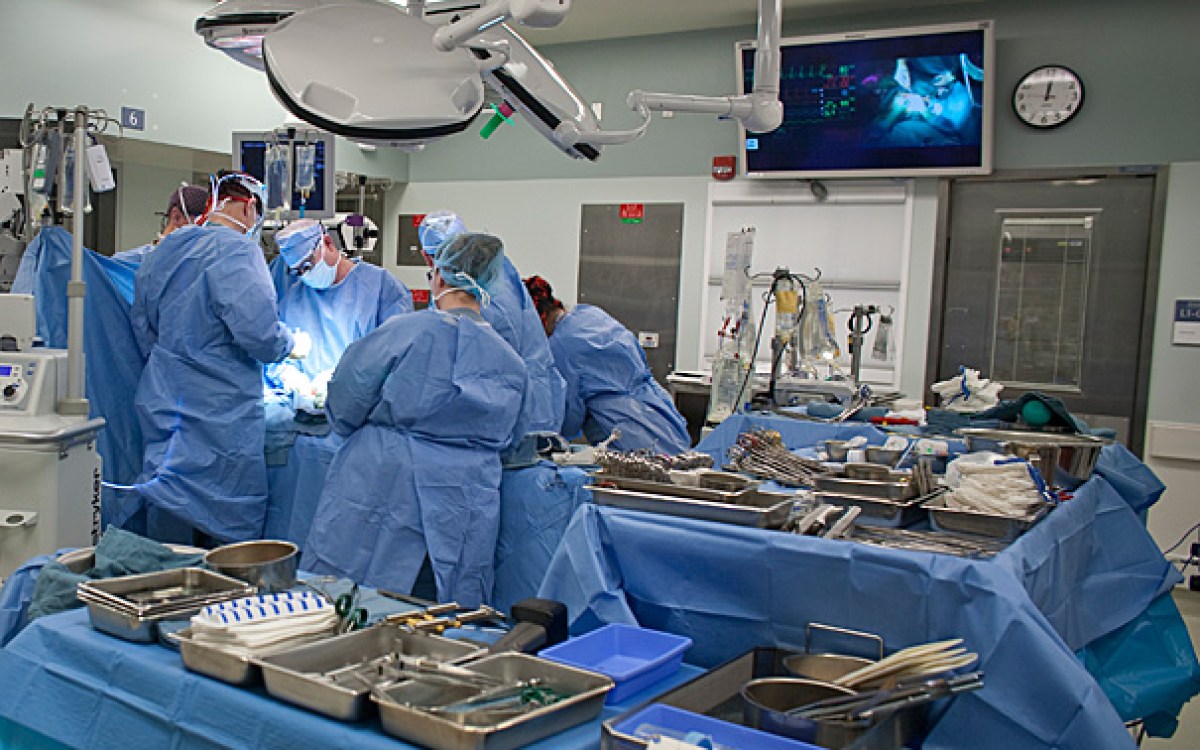

A team of scientists from Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has developed a software-based method of scanning electronic health records (EHRs) to estimate the risk that a healthy person will receive a dementia diagnosis in the future. Their algorithm uses machine learning to first build a list of key clinical terms associated with cognitive symptoms identified by clinical experts, then uses natural language processing (NLP) to comb through EHRs looking for those terms. Finally, the algorithm uses those results to estimate patients’ risk of developing dementia.

“The most exciting thing is that we are able to predict risk of new dementia diagnosis up to eight years in advance,” said Thomas McCoy Jr., first author of the paper.

The team included members of MGH’s Center for Quantitative Health, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. Their paper was published this week in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

The study included data on 267,855 patients admitted to one of two hospital systems. It found that 2.4 percent of patients developed dementia over the eight years of follow-up.

Early diagnosis of dementia could be one of the most important steps toward improving care and finding truly effective treatments for it. Alzheimer’s affects more than 5.5 million Americans at present, and as the population ages that number is expected to balloon. Current early detection tools require additional, potentially costly, data collection. The tool developed at MGH is based entirely on software to make better use of data already generated during routine clinical care. This approach to early risk detection has the potential to accelerate research efforts aimed at slowing progression or reversing early disease.

“The most exciting thing is that we are able to predict risk of new dementia diagnosis up to eight years in advance.”

Thomas McCoy Jr.

McCoy noted that “This method was originally developed as a general ‘cognitive symptom’ assessment tool. But we were able to apply it to answer particular questions about dementia.”

In other words, a general cognitive-symptom detector proved useful for dementia risk stratification. He explained, “This study contributes to a growing body of work on the usefulness of calculating broad symptom burden scores across neuropsychiatric conditions.”

Earlier studies by McCoy and his colleagues used these sorts of tools to predict risk of suicide and accidental death, as well as the likelihood of admission and length of stay among children with psychiatric symptoms in emergency rooms. This latest study suggests that properly tailored, the tool can be applied to more specific questions about other brain diseases as well.

“We need to detect dementia as early as possible to have the best opportunity to bend the curve,” said Roy Perlis, senior author of the study and director of the MGH Center for Quantitative Health. “With this approach we are using clinical data that is already in the health record, that doesn’t require anything but a willingness to make use of the data.”

The researchers hope this tool can be used to accelerate research.

“This approach could be duplicated around the world, giving us more data and more evidence for trials looking at potential treatments,” said Rudolph Tanzi, a member of the research team, vice chair of neurology, and co-director of the McCance Center for Brain Health at the MGH Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number 1R01MH106577), the National Institute of Aging (Supplement to R01MH104488), and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. The sponsors had no role in study design, writing the report, or data collection, analysis, or interpretation.