Keeping home close after you leave it

A still from the film “Remains” by the Northern Ireland artist Willie Doherty.

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Christian A. Herter, Jr. by exchange. © Willie Doherty; image courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York.

Art Museums exhibition explores migration and belonging — while conjuring memories for some visitors

On a recent afternoon, two visitors who know what it means to leave home took in a new exhibit at the Harvard Art Museums, paying particular attention to a work playing on a loop in a black-box theater erected specifically for the show.

In the short film “Remains,” by Northern Ireland artist Willie Doherty, a voice speaks as stark images cross the screen: a burning car; a wind-swept, abandoned lot; a gloomy sky. “It has become a distant memory, taken on the characteristics of a dream. At times I am unsure if it really happened at all,” says the unseen narrator of the brutal kneecappings carried out by the para militants who policed Northern Ireland’s streets during The Troubles, the sectarian conflict between loyalists who wanted to remain in the United Kingdom and republicans eager to have the country join the Republic of Ireland.

For Harvard Divinity School Dean David Hempton and his wife, Louanne, the film — part of “Crossing Lines, Constructing Home,” which explores immigration, home, and belonging with art ranging from vivid photographs to a meticulously hand-sewn installation on the floor — was a searing reminder of the violence they lived through in their home country.

“It speaks to both the mind and the emotions for us. It’s a very evocative look back at images we were very familiar with,” said Hempton, who studied in Belfast during the unrest and moved to the U.S. with his wife, who had worked as a social worker in the city, 21 years ago. “It almost felt to me, I am right there, I know this landscape.”

Back in Northern Ireland recently during the 50th anniversary of the conflict, the couple said they were struck by TV interviews with victims and perpetrators of the violence who spoke of lasting trauma and guilt, and of fears that another physical border between the two countries could emerge as Britain plans its exit from the European Union. “Brexit has been a surprise for people in Britain but not for people in Ireland,” said Hempton, adding that many have half a century of questions about what Northern Ireland’s future holds.

For Louanne Hempton, Doherty’s film touched on those deep uncertainties.

“It brings up bigger questions about how we police our communities, exploit our youth, how we deal with poverty and violence and the legacy of violence … this is about all of our own questions, about all of our deepest fears, all our deepest anxieties, all of our desires, of where we belong.”

Before entering the gallery, the Hemptons chatted with the museums’ Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot director, Martha Tedeschi, who explained how the show speaks to both a specific cultural moment and to the museums’ commitment to contemporary acquisitions. Almost all of the items in the exhibit have been recently acquired.

“We’ve been working toward this moment,” said Tedeschi, “bringing these kinds of new artist investigations of migration and displacement into the permanent collection so when the show is over we don’t lose that possibility of keeping that conversation going.”

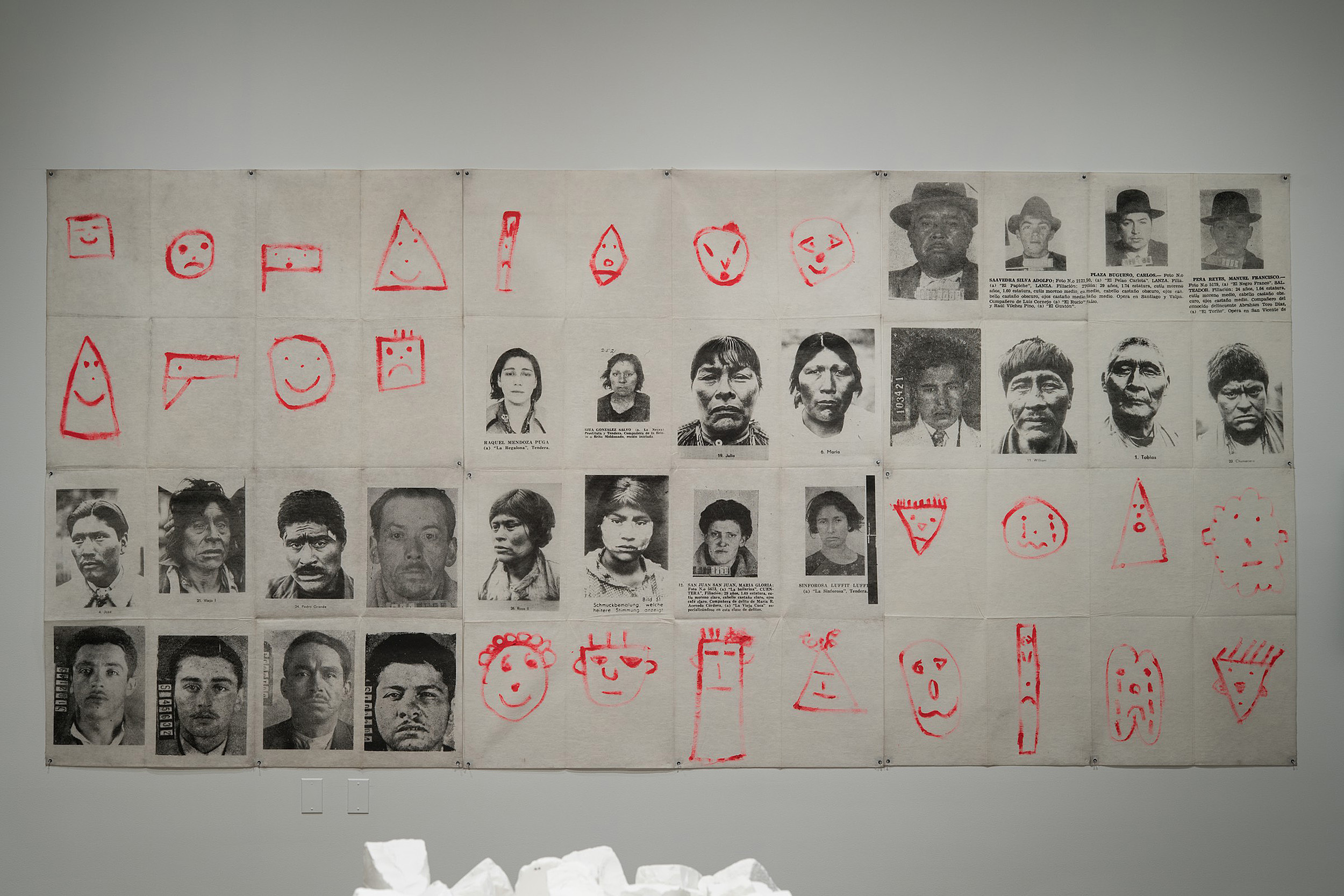

Items in the exhibit range in size and scale, represent myriad cultures, customs, people, and places, and touch on heartbreak, home, and hope. Among the more than 40 works on view are evocative photographs of U.S. border crossings, north and south, taken by American photographers Richard Misrach and Bill McDowell; a large mural by Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn that blends photographs of the faces of people from different indigenous groups in Chile with drawings done by Dittborn’s young daughter; and a delicate reconstruction of a basement corridor in gauze-like fabric that visitors can walk through, created by Korean artist Do Ho Suh.

“2nd History of the Human Face (Socket of the Eyes) Airmail Painting No. 66” (1989) by Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

“We wanted to take the facts about what is happening in our world today and try to make them into an experience for the viewer, for the visitor, that would develop empathy, would develop an understanding of an experience,” said Makeda Best, the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography, who developed the show with Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Mary Schneider Enriquez. “We aren’t trying to cover every conflict, but we are trying to reference and engage a wide range of experiences and identities of crossing lines and constructing home.”

The show comes at a time when themes of displacement and belonging are taking center stage at art exhibits across the country. Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art is currently displaying “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration Through Contemporary Art”; New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is featuring a show titled “Home Is a Foreign Place: Recent Acquisitions in Context”; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is presenting an exhibit devoted to the photos of Richard Mosse, whose camera captured the mass migration and displacement of people that unfolded across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa between 2014 and 2016.

“Museums are really addressing this pressing theme of immigration by using art to help us take a step back and at the same time intimately engage with the issue from a perspective that is not about divisive words or creating walls,” said Enriquez. “It’s about thinking about the human condition and giving voice to those who haven’t had a voice before.”

The myriad voices and perspectives represented in Harvard’s show resonated with Hempton. After about an hour in the galleries, the dean said he appreciated the exhibit’s broad emotional range and its embrace of notions of menace, violence, and harshness alongside the hope inspired by the “creativity of the human spirit” and ideas of belonging.

“It’s a deeper word than inclusivity,” he said. “Belonging is a word that evokes human acceptance and human connection and a genuine sense of being respected and honored.”

For Louanne Hempton, the exhibit called to mind “our deep desire to belong, and home, and what is home for all of us. What dislocation does to all of us … our sense of identity, our sense of being. And how that can be so exploited by other people.”

Like her husband, she said it also evoked hope, pointing to the pictures of two women by Israeli photographer Lili Almog. The women are members of a minority in China who live in their own, female-run Muslim community, where they have crossed lines of gender and religion to carve out a home and a space for themselves.

“You can’t be dislocated if you have a sense of self like these two ladies,” she said. “But if that is stripped away from you, then that’s where it all comes apart.”

Steffany Villasenor ’21 (left) and other students from a Spanish discuss the exhibit with their Spanish professor, Maria Luisa Parra-Velasco (right).

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

María Luisa Parra-Velasco, senior preceptor in Romance languages, took her Spanish 49H students to the show to help them explore the relationship between their use of language and their Latinx identities. As they gathered at the gallery entrance, Parra-Velasco asked the students for words that describe the immigrant experience. Answers ranged from difficult and discrimination to culture, family, and dream.

Anissa Medina offered up the Spanish word for lawyer, abogado. She based her choice on the troubles her grandparents encountered when they crossed into the U.S. illegally from Mexico. They hired a lawyer who promised to help them obtain green cards, but stole their money instead. Their experience, Medina said, highlights the obstacles that often confront those attempting to build a better life in a new place.

“I think a lot of times the topic of immigration becomes really binary; legal versus illegal or documented versus undocumented,” said Medina, “and there are a lot of grey areas that real people have to endure.”

Medina said she was struck by Misrach’s photograph of a border patrol target range in Texas near the Gulf of Mexico. The dramatic image brings up issues of gun control and gun violence, she said, and “the idea that they are literally practicing shooting people who are probably escaping some form of violence or oppression or some form of neglect.”

Harvard Divinity School Dean David Hempton and his wife, Louanne, in front of artist Do Ho Suh’s full-size reconstruction of a basement corridor in a place Suh once lived. “Border Patrol Target Range, Near Gulf of Mexico, Texas,” 2013 by Richard Misrach.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer and © Richard Misrach, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles

Across the room, Suh’s delicate fabric installation connected with first-year student Daniela Diaz, a second-generation immigrant from the Dominican Republic. Diaz said the piece, which questions how people always carry a sense of culture and home with them, resonated with her ongoing efforts to balance her connection to her Dominican and American heritage.

Parra-Velasco’s attention was drawn to one of the more unsettling displays: an installation by the Brazilian artist Clarissa Tossin. For “Spent,” Tossin saved items from her household trash, covered them in porcelain, and fired them in a kiln. The ossified work lies scattered across the gallery’s floor, looking like someone emptied a garbage bin in the middle of the show.

“It was so powerful to make permanent that kind of waste that we don’t even think about but that is part of our daily lives,” said Parra-Velasco.

Jesus Lino ’21 paused in front of a photo of a bus stopped in the middle of a dusty road in Iran. French photographer Gilles Peress snapped the image in 1979 as many Iranians fled the unrest that followed the revolution and overthrow of the last shah. One bus window is covered by a picture of a woman’s face. At first glance her expression appears serene, but “if you look more closely there is a tear,” said Lino. “I think that really struck me because it shows how sometimes there are situations where you have to leave a place you grew up in … because things are so difficult that you can’t remain.”

Many students said they found the range of stories, people, and cultures depicted in the show particularly moving.

“It really shows how universal the theme of migration is and crossing lines and borders and how arbitrary those borders can be,” said Medina, “and how fluid they can be and what they mean to different people based on their circumstances.”