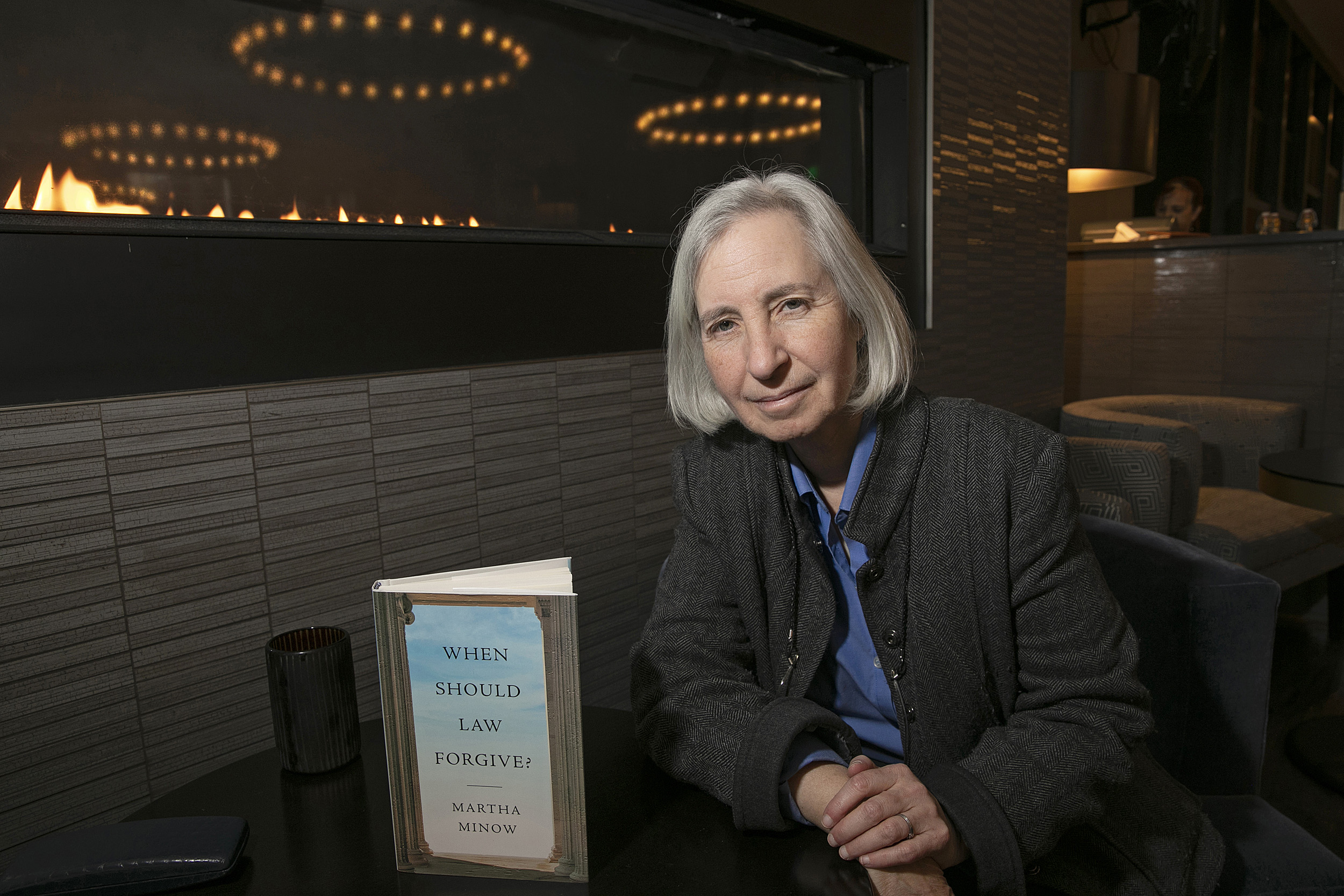

Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary Professor, discusses her recently released book, “When Should Law Forgive?,” in which she argues for more forgiveness in the law and a “jurisprudence for forgiveness.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A plea for mercy

In her new book, legal scholar Martha Minow advocates for the power of forgiveness

In her new book, “When Should Law Forgive?,” Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor, explores the possibilities for the U.S. legal system to become less punitive and more merciful. The Gazette sat down with Minow, former dean of Harvard Law School, to talk about her book and why she thinks forgiveness could make the law more just.

Q&A

Martha Minow

GAZETTE: How do you define forgiveness, and why it is important for the U.S. legal system to be more so?

MINOW: I define forgiveness as letting go of justified grievance or resentment. Our country right now is presiding over the most incarcerating criminal justice processes in the history of the world. We have the most people incarcerated per capita. But my larger concern is that we have techniques for forgiveness built into the law, but we don’t use them consistently, and we don’t use them with any criteria of fairness.

GAZETTE: In your book, you say that the U.S. criminal system is very punitive. When and why did it become so punitive? Did race play a factor in this evolution?

MINOW: I have no doubt that race plays a very large factor in this development. My wonderful colleague, no longer with us, Bill Stuntz, wrote a crucial book on exactly how our criminal justice system became the way that it is. First of all, it’s not one system; it’s very decentralized, divided in localities, states, etc. But one of his points is that we typically elect the prosecutors in most places; and it’s easier to win an election saying that you will be punitive than saying that you won’t be, and to say you’ll put more people in prison, and you’ll have longer sentences. It’s also been the fact that we have a history of racial division and racial oppression in this country. You don’t have to agree with everything in Michelle Alexander’s book “The New Jim Crow” to see the patterns of racial discrepancy in incarceration rates and sentences. There’s something pernicious in the continuing racial divide in our criminal justice system.

GAZETTE: You argue that bankruptcy law is a technique for forgiveness built into the U.S. legal system, but you also say that the law tends to forgive corporations more than individuals. Why is that and how does it relate to the issue of fairness?

MINOW: The U.S. Constitution has a provision that gives Congress the power to enact a national bankruptcy law, which was a priority for the founding fathers, particularly for Thomas Jefferson, who himself was in debt during much of his life. He understood the importance of having the chance to have a fresh start, and he developed a political theory about why one generation should not burden the next with its debts. Bankruptcy practices in the United States are associated with the tradition of innovation, entrepreneurship, and risk-taking. But bankruptcy law has been subject to all the political processes of all of our laws. In its current iteration, it is much more forgiving of corporate debt than it is of individual debt. It makes it possible for a for-profit school to go bankrupt, but students who took out loans to go to that school cannot expunge their debts to bankruptcy. And that reflects the political process, power imbalances, and unfairness.

“It’s also been the fact that we have a history of racial division and racial oppression in this country. … There’s something pernicious in the continuing racial divide in our criminal justice system.”

GAZETTE: You also say that the U.S. legal system could learn to be more forgiving of minors involved in criminal activity based on how international law deals with child soldiers. How should forgiveness work in such cases and what effects it would have?

MINOW: The situation of global and local conflicts that draw minors into violent disputes and wars that are really conducted by adults has generated important innovations in international law. The very first case pursued by the International Criminal Court against Thomas Lubanga charged him and convicted him of the crime of recruiting and coercing minors to participate in armed conflict. That made an innovative recognition that there’s blame to be had here, but it should be on the heads of the adults.

The U.S. once upon a time had the innovative idea of separate courts for juveniles. Over time we’ve drifted so that we treat juveniles like adults if they commit serious crimes, and they can be locked up for life without parole. We could learn from the international context to see that there are adults who are responsible for setting up a world in which the young people are drawn into those conflicts. And it’s not to say that the juveniles have no responsibility, but that we can locate that responsibility in that larger context and provide opportunities that give those young people a chance for a fresh start, the same way we do in bankruptcy, where we give businesses the chance for a new start.

GAZETTE: How do you envision a change in the legal system toward forgiveness? Are you asking for new laws or more forbearance in the administration of law?

MINOW: I’m very encouraged myself by the recent election of progressive prosecutors who ran on the platform that they want to come up with ways to divert juveniles from the criminal system or to allocate the scarce resources of the prosecutor’s office to the most serious crimes rather than to low-level drug offenses. We have several now in cities across the country — in Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco. What I see is the system working in a good way, where voters are seeking a more forgiving legal system, and yes, one that uses forbearance, but also explicit guidelines about when to use the criminal system.

The bankruptcy process should be revised so that it is less punitive for individuals. But both processes, the election of the prosecutors and the changes in the bankruptcy system, are political. There are other changes within the legal system that I would like to see, and that includes the development of clear guidelines and usable procedures, for example, for expunging a criminal record. We have that capability but in most places it’s very hard to do; it’s hard to understand and hard to navigate. The same thing happens with sealing a record for minors.

Another topic I deal with in the book is pardons, which is the capacity that governors and the president of the United States have to pardon a crime. It would be a better world if we develop guidelines for the use of that power. There are other countries that don’t leave that power simply in the hands of one person. The pardon power is one in particular where there’s great risk of abuse, due to the access that those with more power or visibility have.

“We should remember the purposes of strengthening human relationships and helping people overcome trauma and helping societies rebuild after terrible atrocities; and we should revise the legal system to make those goals better served.”

GAZETTE: Who should not be forgiven?

MINOW: I above all believe that this is a subject that deserves much more attention. We’re living in a time of resentment, and this country and other countries could gain by exploring the power to forgive that every religion has cultivated. Legal systems going back to Hammurabi’s Code and the Jubilee in the Bible have recognized that there needs to be a reset, a start over. At a minimum, we need more conversation, but of course, that means discussion about what’s not forgivable. For example, we have a statute of limitations for most crimes. Murder is so serious that even if it’s 20, 30 years later, you can still be prosecuted. And I think that is appropriate.

But there are some aspects of the legal system itself that are unforgivable. For example, the use of fines and fees laid on top of the punishment for poor people and the court systems that use them knowing full well that the individuals cannot pay them, which leads to incarceration despite the fact that the Supreme Court has said we should never have a debtors’ prison. That’s unforgivable. One of the important elements of thinking about forgiveness is that those who commit wrong should always be thinking about, “What can I do to make it better?” I think the legal system has to make the legal system better.

GAZETTE: What impact would you like your book to have?

MINOW: I’ve been teaching almost 40 years in law school, and I realized that law schools don’t usually teach about forgiveness. I would like there to be discussion and education in law schools and in society generally about forgiveness: When should we forgive? When should the legal system forgive and when should it not forgive? How do we cultivate forgiveness and when should we not cultivate it? I explore in the book particular devices of forgiveness, as well as the possibility of creating legal systems that allow people to forgive one another. The use of restorative justice in criminal justice to bring people together, offenders and people who’ve been victimized, and allow them to talk with each other is very promising.

I hope an impact of the book is to encourage people to take seriously the possibility of the legal system encouraging and supporting future-oriented solutions rather than always looking at the past and always looking to blame. Justice itself is seeking a response to wrongs but can be judged by whether the responses are proportional or whether they serve human ends. We should remind ourselves that we’ve created criminal and bankruptcy law to serve goals in the same way that every religion, every society, every civilization has promoted the development of apology, forgiveness, compensation, and restitution. We should remember the purposes of strengthening human relationships and helping people overcome trauma and helping societies rebuild after terrible atrocities; and we should revise the legal system to make those goals better served. We need more forgiveness, but we need a jurisprudence for forgiveness.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.