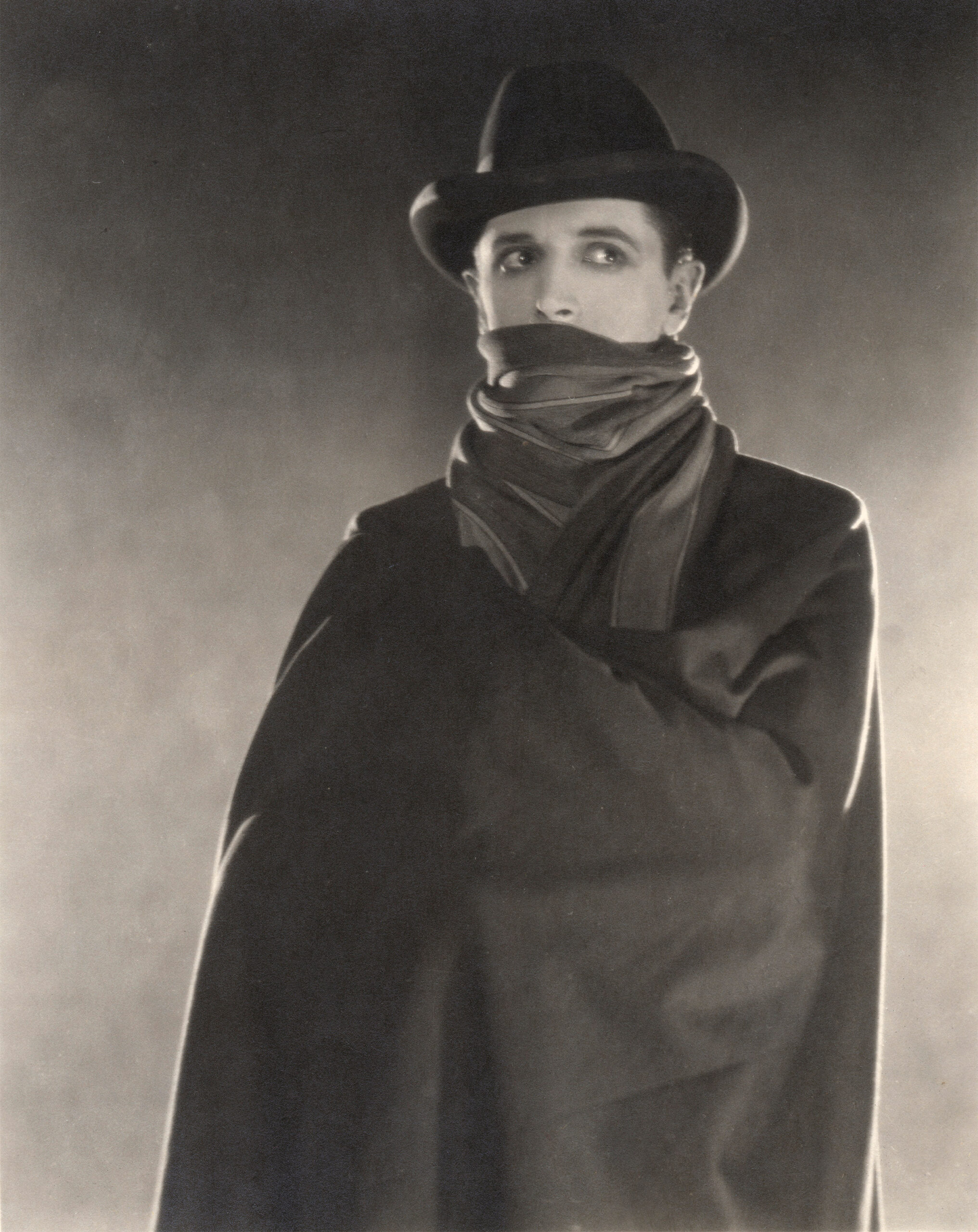

Alfred Hitchcock was only 25 years old when he made “The Pleasure Garden.”

Courtesy of Park Circus

Hitchcock’s silent side

Harvard Film Archive to screen famous director’s silent-era films

His name is synonymous with titles such as “Psycho,” “Vertigo,” and “Rear Window,” just a few of the suspense-filled classics made by one of the most influential filmmakers of the 20th century. But what may come as a surprise to many moviegoers is how English director Alfred Hitchcock honed many of his trademark techniques and themes in silent films. Equally surprising is that many of Hitchcock’s 1920s movies were comedies or quiet dramas, not thrillers. For the next month the Harvard Film Archive (HFA) will showcase those earlier works, a set of nine films on loan from the British Film Institute, which restored and rereleased the 35 millimeter prints in 2014. The Gazette recently spoke with HFA Director Haden Guest about Hitchcock’s early efforts and inspirations.

Q&A

Haden Guest

GAZETTE: Why choose a series devoted to Hitchcock’s early silent films?

GUEST: Alfred Hitchcock is one of the most iconic and influential filmmakers of all time, a hyperbolic but accurate claim, and yet his early silent films for many reasons remain less well known. A number of years ago the British Film Institute restored several of the nine extant films Hitchcock made during the silent era, the first, “The Pleasure Garden,” made when he was only 25 years old. The HFA program includes all of these films. What’s incredible about these early works is how clearly you can see and understand his emergence as the master of suspense: You can find many of the key ideas of Hitchcock’s mature cinema expressed vividly in his silents, especially in “The Lodger,” his film about a mysterious tenant who might be a serial killer, a film about shifting identity and doubt that points all the way forward to “Psycho” in 1960.

GAZETTE: Can you say more about how his silent films highlight some of his earliest creative inspirations?

GUEST: Hitchcock’s ability to push the possibilities of film as an expressive medium is wonderfully showcased in these early films: how to tell a story efficiently and expressively through images, something that continues throughout his career. Think about the dialogue-less opening sequence in “Marnie” with its extended close-up of Tippi Hedren’s handbag, or the masterful crop-duster scene in “North by Northwest,” also largely dialogue-free. At the same time, Hitchcock was very much influenced by certain trends and movements of the silent era, most especially German Expressionism, a kind of imaginative thinking about space, and place, and mood. He was deeply interested in contemporary German cinema and spent time at the Ufa studios to study how films were being made there. Hitchcock’s first two films were, in fact, made in Germany. But it is his third film, “The Lodger,” that best reveals a Germanic influence: The film is steeped in the fatalist, gothic modernist style of German Expressionism.

Lilian Hall-Davis and Carl Brisson in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 film “The RIng.”

Courtesy of Rialto Pictures

GAZETTE: It seems surprising that many of the films in this collection aren’t the suspenseful thrillers he is known for, but comedies and dramas.

GUEST: Hitchcock was still a journeyman filmmaker in the 1920s and so he was making films to establish himself, to prove his viability as a filmmaker who was tasked to make a wide range of work in different genres early on. The results are quite remarkable, and singular in his career: the thrilling boxing movie “The Ring,” which is also a wonderful romance, as is “The Manxman,” which is perhaps his finest silent film. But I would point out that threads of the romance and of the comedy are woven throughout Hitchcock’s oeuvre. Consider, for example, the comic aspects of “Rear Window,” or the lesser-known “The Trouble with Harry,” which really is a kind of black comedy. The vein of romance in Hitchcock’s cinema runs deep, as exemplified by “The 39 Steps” and “Notorious,” to name just two titles. I would say that Hitchcock’s later works are really hybrids; they have elements of melodrama, of comedy — even bringing in screwball elements at times — and of romance. This was one of Hitchcock’s unique talents, the ability to intermingle genre registers and switch from one to the other. Think about the rich comic repartee between Barbara Bel Geddes and Jimmy Stewart at the beginning of “Vertigo,” for instance, a film that becomes, in its second half, one of Hitchcock’s darkest and most haunting works. He was able to pivot between these different registers in fascinating ways, registers that are expressed in pure form in the silent films.

Hitchcock’s darker side was reflected in the 1927 crime-thriller “The Lodger.” He turned to romance in the 1929 film “The Manxman.”

Courtesy of Park Circus and Rialto Pictures

GAZETTE: In a series of interviews with French filmmaker François Truffaut in 1962, Hitchcock said, “Silent pictures are the true motion picture form” and that “so many of the [sound] films made today are photographs of people talking.” What do you think he meant? And what did he think talking pictures missed?

GUEST: Hitchcock wasn’t alone. Many people at the time — including influential filmmakers and critics — bemoaned the coming of sound, for with sound came the death of cinema as it was until then, the silent film. The expressive potential of the human face was explored to its fullest in silent films, a lesson that Hitchcock never forgot. Think about the climactic scene in “Vertigo” when Jimmy Stewart sees Kim Novak after he has transformed her from Judy back into Madeleine. There’s a long shot of Stewart’s face that is so moving. It’s a moment of rapture and also perhaps terror, seeing the dead brought back to life. I really think that comes from Hitchcock’s background in silent cinema, that extended shot of the face. This idea that dialogue was secondary to the larger possibilities of the cinema to tell a story, to create emotions, to invent kinds of movement across images and within the audience; a quickening of the heart. This is why you can study many Hitchcock films really purely in terms of the image. Yes, he worked with incredible screenwriters in films like “Strangers on a Train,” with its extraordinary dialogue. And “Psycho” has an incredible screenplay. Yet, I think Hitchcock’s highest priority was always the image, and that’s something he took from silent films. Many felt that sound was an abomination, never necessary, and an added distraction. Going forward, Hitchcock always used sound very judiciously; even in films where there is quite a lot of it, he is always doing something to counterbalance dialogue with the image.

GAZETTE: How did music factor into Hitchcock’s silent and sound films?

GUEST: It’s important to remember that silent cinema was never silent but was always accompanied by music of some sort, sometimes by a piano, other times with larger ensembles. This is something else that Hitchcock learned from his early films. He would go on to work with some of the greatest composers, most famously Bernard Herrmann, who were among his most important collaborators. The term melodrama, which derives from melos, Greek for music, makes clear the inextricability of music and drama, something that silent cinema fully understood, the power of music to move the film, to move the audience.

We are also great lovers of silent cinema here at the Harvard Film Archive and this is a chance to present these works as they should be seen, as beautiful film prints on the big screen with live musical accompaniment. For this series we are very lucky to have pianist-composers Martin Marks and Robert Humphreville, and guitarist-composer Bertrand Laurence alternately providing the music. These are going to be great shows and performances.

The Harvard Film Archive’s “Silent Hitchcock” begins Saturday and runs through Feb. 15.

Interview was edited for space and clarity.