David Liu and his team are researching how to make gene editing more precise.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

A crisper CRISPR

Fewer off-target edits and greater targeting scope bring gene editing technology closer to treating human diseases

Not too long ago, CRISPR was a cryptic acronym — or, to some ears, a drawer to keep lettuce fresh. Today, CRISPR Cas9, the most popular form of the powerful gene-editing technology, is widely used to accelerate experiments, grow pesticide-resistant crops, and design drugs to treat life-threatening genetic diseases like sickle cell anemia.

But CRISPR is not perfect. Base editors (think of them as gene-editing pencils) can rewrite individual DNA letters. They home in on specific areas of DNA and swap out certain bases — A, C, T, or G — for others. But after the swap, base editors—like the cytosine base editor that converts C•G to T•A — perform unwanted off-target edits. Until now, even the best CRISPR tool, SpCas9, could only bind to about one in 16 locations along DNA, leaving many genetic mutations out of reach.

Now, in two papers published in Nature Biotechnology, researchers at Harvard University, the Broad Institute, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute have invented new CRISPR tools that address both issues. The first paper describes newly designed cytosine base editors that reduce an elusive type of off-target editing by 10- to 100-fold, making new variants that are especially promising for treating human disease. The second describes a new generation of all-star CRISPR-Cas9 proteins the team evolved that are capable of targeting a much larger fraction of pathogenic mutations, including the one responsible for sickle cell anemia, which was prohibitively difficult to access with previous CRISPR methods.

“Since the era of human genome editing is in its fragile beginnings, it’s important that we do everything we can to minimize the risk of any adverse effects when we start to introduce these into people,” said David Liu, the lead author on the papers. “Minimizing this kind of elusive off-target editing is an important step toward achieving that goal.”

Reduced off-target editing

Liu, Richard Merkin Professor, vice chair of the faculty, and director of the Merkin Institute of Transformative Technologies in Healthcare at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, set out with his team to pinpoint those troubling and erratic CRISPR-independent off-target edits.

“That type of off-target editing can occur at random locations in the genome,” said Liu. “When you run the experiment 10 times, you get 10 different answers. That makes it so challenging to study.”

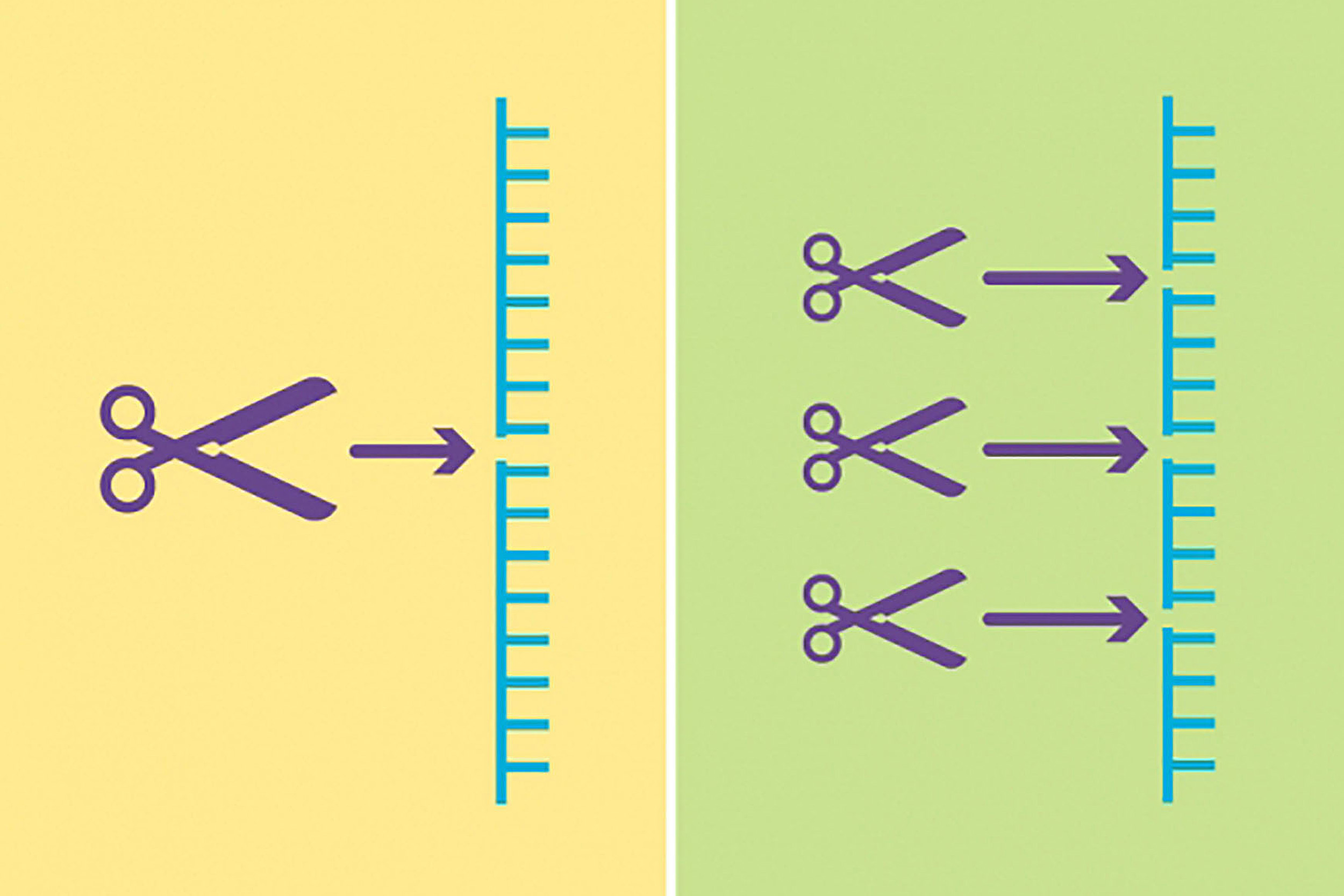

Two new updates give CRISPR gene-editing technology access to difficult-to-reach areas of the human genome and more precise editing capabilities.

Illustration by Susanna Hamilton/Broad Communications

One way to detect CRISPR-independent edits is to sequence the entire genome many times. But such experiments are time-consuming and expensive — tens of thousands of dollars. Instead, Liu and his team designed five new tests that avoid whole-genome sequencing and are both fast and cheap. In one, they sent in a different CRISPR protein to hold the strands of a DNA double helix open at six different locations in the human genome. Base editors strongly prefer to edit single-stranded DNA, so the open strands attract any misbehaving base editors. “By holding the strands open, this assay invites a cytosine base editor to come in and edit in the opened DNA if it’s prone to do so,” Liu said.

Then Liu and his team simply searched for base edits in the six open DNA strands. In their first study, they sequenced the whole genome to verify their assays matched the results of the slower and expensive, but proven, method — and they did.

Next, Liu tested all 14 major types of cytosine base editor to determine which produced fewer off-target edits. The variant YE1 won: “Even if we held a bunch of DNA loops open enticingly for it to edit, it wouldn’t bite,” Liu said. Since YE1 had a smaller reach than other variants — when parked on DNA, it could only edit the three closest bases — he and his team engineered the tool to reach farther, across five bases. The result is a more precise, selective and versatile suite of base editors.

More ground to cover

CRISPR has another hurdle to overcome: its limited ability to access the entire human genome. “You can’t actually park Cas9 anywhere in the genome,” Liu said. “You can only park it in places that have a small constant sequence of DNA, called a PAM.”

Until now, the most common PAM was NGG, where “N” is any base. But two consecutive Gs only occur in about one in 16 places in the genome. “One out of 16 is bad odds,” Liu said, before calculating the exact probability — 6.25 percent — in a couple of seconds.

In 2018, Liu and his lab evolved variants of Cas9 that could recognize some DNA sequences with one G, expanding CRISPR’s reach to one in four. “But among the untrodden territories of SpCas9 are PAM ‘deserts’ that don’t have any Gs,” he said.

“Since the era of human genome editing is in its fragile beginnings, it’s important that we do everything we can to minimize the risk of any adverse effects when we start to introduce these into people.”

David Liu

Using a previous invention, phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE), Liu and his team forced SpCas9 to evolve quickly, creating many new generations of the protein in about a week (without PACE, the process takes months or years). Their goal was to produce new SpCas9 proteins that had all the talents of their mom protein but greater versatility. Only proteins capable of recognizing PAM sequences without a G survived the Darwinian selection.

“Out came these three families of SpCas9 variants,” Liu said. Collectively, they can direct both cytosine and adenine base editors and park at almost any NR, where R is either an A or a G, giving them access to roughly half of DNA sites. With base editors able to reach across a five-base window to perform edits, the likelihood of a five-base window without an A or G is just 5 percent. “Ninety-five percent of pathogenic point mutations that we know of have an NR PAM in the right place to support base editing,” Liu said. This means base editors can now reach and correct up to 95 percent of point mutations that cause disease.

For example, the difficulty of accessing the base mutation that causes most cases of sickle cell anemia had hampered efforts to treat it. “By bad luck, it doesn’t have an NGG in the right place for SpCas9 base editing directly on the sickle cell mutation,” Liu said. “As a result, it’s [been] challenging to use published base editors to go after that site.

“And sure enough, using one of the evolved SpCas9 variants that can park at a CACC PAM, we can now base edit this mutation quite efficiently.”