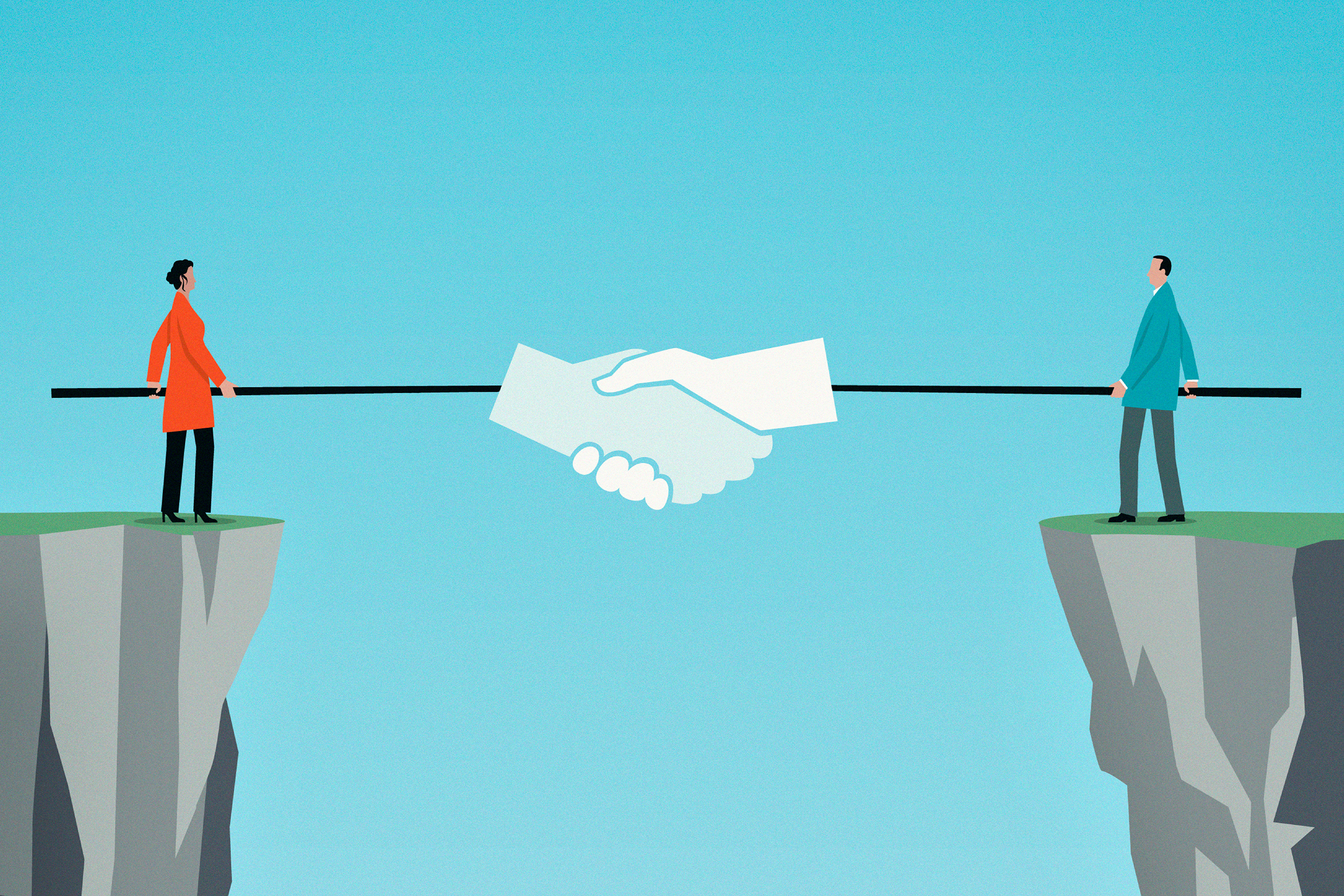

Illustration by Mark Airs

Wither the handshake?

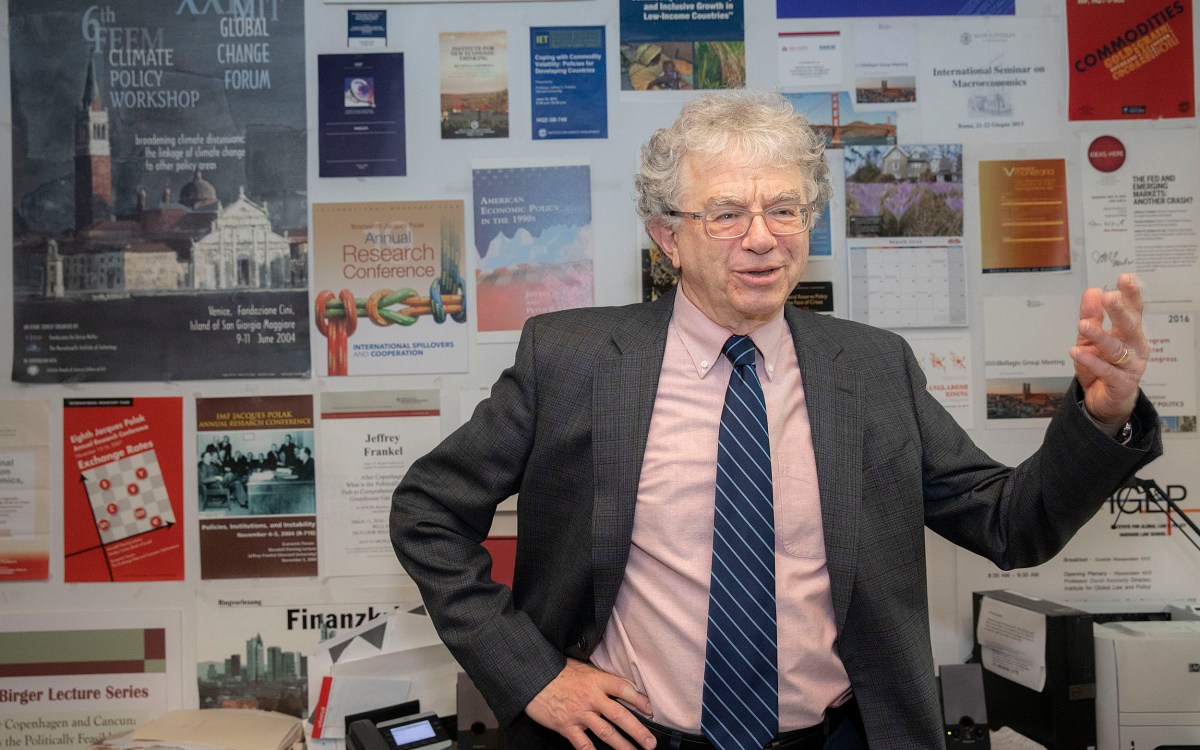

Harvard experts weigh in on the origin and fate of the universal greeting

Long-held habits have disappeared overnight as social distancing has become both a rallying cry and the new normal for millions of Americans in the age of the novel coronavirus. But keeping at least six feet from another person — the guideline issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — is a challenge for people accustomed to saying hello and goodbye with hugs and kisses.

And what about the handshake?

Some have begun to wonder if the universal form of greeting, of acknowledgement, of sealing a deal may become a thing of the past. In recent weeks the practice has rapidly vanished, replaced by fist bumps and peace signs, head nods and foot taps, all in an effort to limit the close contact that helps the virus spread.

Response to the pandemic changes daily, and stricter social-distancing measures, government aid, and testing have all increased dramatically since the Gazette spoke with William Hanage, associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, earlier in the month. Hanage said he hopes the handshake is just on extended hiatus, but for now he’s keeping his hands away from anyone else’s.

“When I go to my neighborhood sports bar and see my friend who works there, I give him a big handshake and a hug. I love it. I am not one of those people who in winter and virus season carries around hand sanitizer and uses it a great deal,” said Hanage, who stopped shaking hands several weeks ago. “The major difference is that here we are dealing with a disease to which we have no immunity, and to which we can pretty sure we are going to be getting exposed.”

While the human hand is a nifty carrier of viruses, germs, and bacteria, the human body’s immune system is typically equally gifted at coping should one, say, touch their eyes, nose, or mouth. But with the novel coronavirus raging, said Hanage, for the moment all bets are off.

“People accompany these gestures with a little laugh, as if to reassure each other that the superficially aggressive displays are new conventions in a contagious time and offered in a spirit of camaraderie.”

Steven Pinker, Harvard’s Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology

“People say that the close study of infectious diseases goes one of two ways, either you become incredibly paranoid, or you eat the peanut butter toast that fell face down. I am the latter. That is what I do for a living. I sit there and think, ‘Evolution has given me this amazing immune system, this fantastic, phenomenal thing which allows me to recognize and squash most of the stuff that I am likely to encounter.’ Now is not one of those times.

“Because this is a pandemic, because there is virtually no population immunity, and because we know that people can transmit while being either presymptomatic or showing minimal symptoms, every handshake that you have runs the risk of exposing you or the person you are shaking hands with to the virus.”

Even the elbow bump puts people in closer contact than Hanage thinks is truly safe. Instead, he recommends the Hindu namaste greeting: a slight bow, with the hands pressed together in a prayer pose over the heart.

“Handshaking is just one of the ways that we are more likely to become infected, and so it’s a really easy thing to remember to do something else,” said Hanage. “There are multiple different options that are available to say ‘hi’ to your friend that don’t entail getting quite so close. Because every time you are getting close, you might transmit to them, or they might transmit to you.”

When will it be safe to shake hands again? Like many experts tracking the disease’s course, Hanage can’t give an exact timeline. Still, he does think it will happen “in the distant future when the virus is under control.”

“I sit there and think, ‘Evolution has given me this amazing immune system … which allows me to recognize and squash most of the stuff that I am likely to encounter.’ Now is not one of those times.”

William Hanage, associate professor of epidemiology

But why are we so attached to such a gesture, one that some say originated in ancient times as a way to show a potential foe that you were unarmed? The answer likely has something to do with our DNA, according to Steven Pinker, Harvard’s Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology who points to the “Principle of Antithesis” detailed in Charles Darwin’s “Expression of Emotion in Animals and Man.”

“In order to display a friendly, nonthreatening intent, animals often evolve a display that is the joint-for-joint, muscle-for-muscle opposite of their display for aggression. So a friendly dog assumes the opposite posture from an aggressive dog: instead of a rigid tail and body with the head poised forward as if to attack, it will crouch, look upward, and wag its tail,” Pinker wrote in an email. “In the case of humans, too, friendly displays tend to be the antithesis of threatening ones: our hands are open rather than clenched, our arms are supinated, we approach the other person closely rather than keeping the wary distance of two fighters, and we expose vulnerable body parts like our lips and neck.”

Through time, every culture has to adopt conventions about which gestures are put into practice, said Pinker, “to eliminate any ambiguity about just how friendly the intent is.”

Conventions differ across cultures, he points out.

“Many Americans were taken aback when George W. Bush held hands with his Saudi counterpart, since a quick handshake is the maximum touching sanctioned for American men,” Pinker said.

When it comes to the handshake and the coronavirus, “fear of contagion could certainly change the conventions as well,” noted Pinker, “but with an interesting twist.”

“Displays guided by Darwinian antithesis are just those that spread germs — contact, proximity, and exposure of the mouth and nose — whereas sanitary conventions like fist-bumps and elbow-taps go against the grain of intuitive friendliness. That explains why, at least in my experience, people accompany these gestures with a little laugh, as if to reassure each other that the superficially aggressive displays are new conventions in a contagious time and offered in a spirit of camaraderie.”