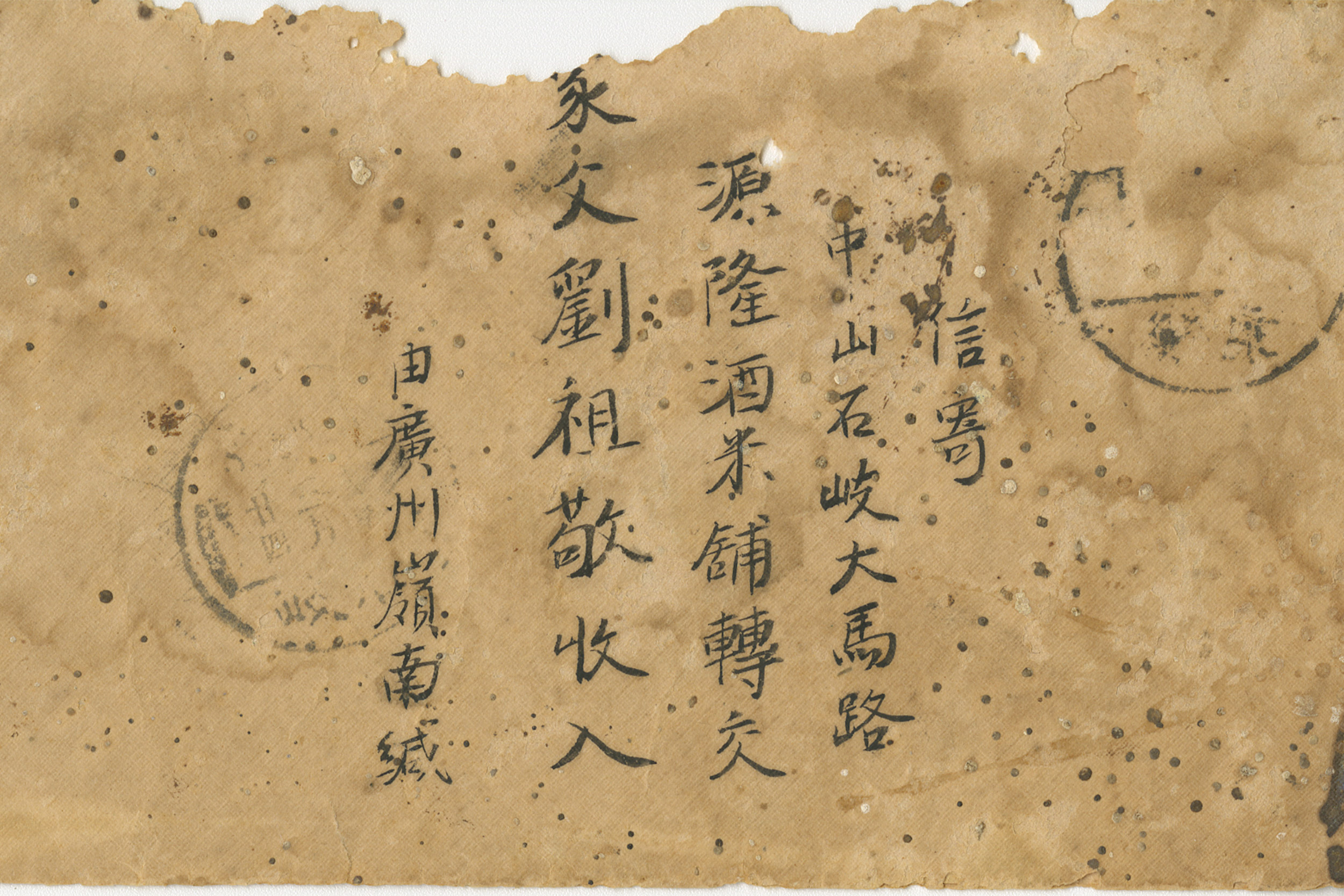

From the “Papers of Pin Pin T’an Liu,” who earned a master’s degree from Radcliffe in 1938: an undated photograph that includes her grandfather, Chang Yin T’ang (seated on left).

Images courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Diversifying Schlesinger’s records

Library continues to broaden its collections

Lucy Stone, Angela Davis, Betty Friedan, June Jordan, Julia Child, Mildred Jefferson. All of their lives and stories are captured in the rich collections housed in Harvard’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

And thanks to ongoing efforts to diversify and broaden the library’s holdings, new names are regularly added to their number: such as poet, writer, and former Radcliffe Fellow Marilyn Chin; ordained minister, Harvard Divinity School graduate, founder of the Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence and the first all-female Asian Lion dance troupe in Boston Cheng Imm Tan; and an immigrant from China who earned a master’s degree in English literature from Radcliffe in 1938 and went on to host a popular U.S. radio show, Pin Pin T’an Liu.

Take Liu’s collection, with material in both English and Chinese such as immigration documents, recipes, personal photos, and more. The recently acquired archive highlights the library’s decades-long work of honoring the efforts and achievements of women, as well as its commitment to continually seeking out the material records of an ever-wider range of female changemakers, along with those whose quieter lives and everyday experiences comprise the diverse tapestry of American history.

“If we are going to tell complex stories about diversity and its value and move toward genuine inclusion, then we need to have the archives which support that work,” said Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library Jane Kamensky.

Over the last several years library staff have been discussing how to make its collections “more representative of the experience of women in the United States and therefore more accurate and important,” added Kamensky. Those conversations drove the creation of advisory and working groups that will help build connections to and relationships with communities that have been less represented in the archives in the past. A new working group, centered on women’s roles in the making of modern conservatism, will begin meeting under Kamensky’s direction next month.

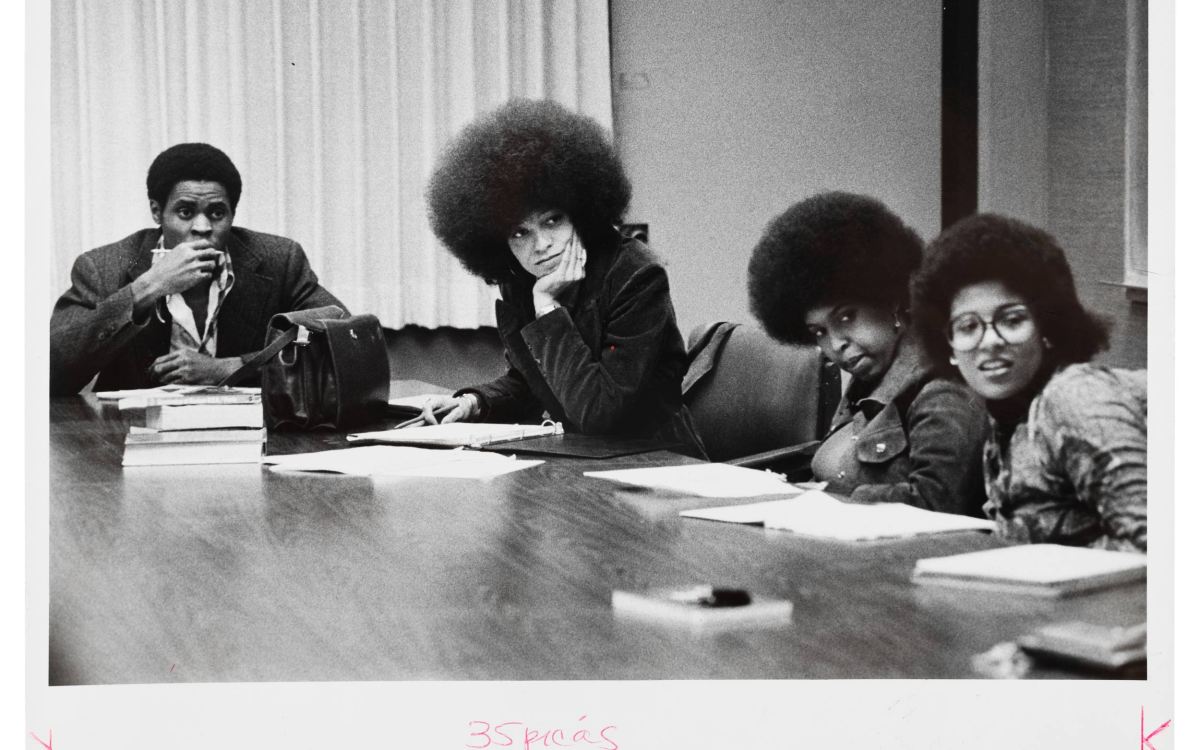

Diversifying the records can be complicated, sensitive work, said Kenvi Phillips, the library’s first curator for race and ethnicity, who was hired in 2017 to help the library develop a more inclusive archive. Phillips, who was part of the team that brought Davis’ papers to Schlesinger in 2018, knows different communities have different concerns and constraints and that learning to be sensitive to a group’s particular interests or worries, as well as what questions to ask, takes care and time. To help her reach out to the Asian American diaspora, Phillips helped organize the library’s Asian American Women’s Advisory Group made up of alumnae representing Chinese American, Korean American, Filipina, and South Asian communities.

“They have been incredibly helpful in walking us through different strategies for how to approach people; they are planning networking events for us in New York and San Francisco; and they are even offering up different names of people who might want to share their stories,” said Phillips.

“If we are going to tell complex stories about diversity and its value and move toward genuine inclusion, then we need to have the archives which support that work.”

Jane Kamensky, Schlesinger Library

The advisory group includes Jeannie Park ’83, a co-founding board member of the Coalition for a Diverse Harvard and president of the Harvard Asian American Alumni Association. Park called it an honor “to get to work with this inspiring group of connected and deeply engaged Asian American women leaders.” The group is now helping library staff think through a range of issues central to Asian American women as they work to expand their collections.

“Immigration is certainly a huge factor when talking about the Asian American community. Language issues may be a barrier. Women may be keeping journals or notes in non-English languages, or may not even speak English,” said Park. “They may also have brought very little with them to this country. They may have escaped war or other disasters and trauma. My mother, for instance, has almost no photographs from her childhood because she lost almost everything, multiple times, in the wars in Korea and in escaping from North Korea. That’s not uncommon.”

And while Kamensky anticipates new collections arriving in different languages, she isn’t worried.

“The hidden subtext of this whole effort is the language expertise of the Harvard Library bibliographers, assuming that we continue to succeed in collections that have pieces in Mandarin and Cantonese and Thai and Lao and Vietnamese and Hindi and on and on. Schlesinger can’t hire language experts to do that processing and we don’t have to, because Harvard Library already has it. In order to describe and carefully process the collections we will be leveraging the talents of our Harvard colleagues, which is a great gift.”

The recent seminars hosted by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study have supported the library’s ongoing efforts. In 2016 the institute hosted “Native Peoples, Native Politics,” a daylong conference that capped a year of scholarly programs and initiatives at Harvard inspired and/or led by indigenous peoples. The 2018 symposium “Who Belongs? Global Citizenship and Gender in the 21st Century,” and 2019’s “Unsettled Citizens” were part of a two-year thematic focus on citizenship timed to coincide with the centennial of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, and the 150th anniversary of the 14th Amendment that granted citizenship to anyone born or naturalized in the U.S.

“I hope this work ignites interest in the Schlesinger among Asian American women who may not even know about the library,” said Park. “I hope they start thinking about the importance of saving our history, about the legacy of their own papers and about the Schlesinger as a home for them.”