Illustration by Gary Waters

What scares you most about climate change?

Experts tease out the scientific, legal, economic, political, and philosophical costs and benefits of the problem — and the solutions

To mark Earth Day’s 50th anniversary, amid the coronavirus pandemic, the Gazette contacted experts on climate change, the environment, and sustainability to ask them about their global-warming fears. Here are their answers.

Thomas P. Gloria

Program Director, Sustainability, Harvard Extension School

This question presupposes that I am scared about climate change. How dare you ask such a question to a career sustainability professional? Being scared is being afraid, terrified, and at worst, emotional to the point of being catatonic. I demand, no, I respectfully deserve a better question, a positive, uplifting question, especially on the 50th anniversary of Earth Day …

I am scared, deeply. We are in a climate crisis.

My Rachel Carson moment of being present to the enormity of the challenges that come with global climate disruption happened when I was a doctoral student at Tufts just starting my background literature search. It was 1994, and Nature just published a journal article by [James E.] Lovelock and [Lee R.] Kump (1994). When disruption occurs, it comes with accelerating forces due to failures of climate regulation, unleashing reinforcing feedbacks that further amplify increases in global temperatures.

My fear is, despite the science and the early warning signals that we bear witness to — record temperatures, 1,000-year storms, glacial retreat, coral reefs dying on a continental scale — global society may finally wake up, but it may be too late. Our current global political economy solves problems through business as usual growth, wasting precious time to effectively reduce emissions to prevent human suffering and ecological system collapse at an unimaginable scale.

I may not live long enough to experience the severe effects of climate change. However, when I look around the Harvard community, a truly global community, I see a growing younger generation of people who will experience severe impacts. They get it. They don’t need to be told (again) how bad it’s going to get. They know.

So I respectfully pivot to the question posed and answer this question: “What about climate change brings me hope?”

Sustainable development is most frequently defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This tried and true quote from the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, a.k.a. the Brundtland Report of 1987, is truncated. In Section 3, subparagraph 27, the definition begins with “Humanity has the ability to make development …”

Humanity, the human collective, has the ability to take control of the physical world it disrupts with an alacrity just like the natural world’s reinforcing feedbacks loops, but in a good way. With courage, leadership, and a moral compass to make the world a better place, together, the Harvard community has the ability to make a difference on a global scale that will inspire others to also make a positive difference. And this gives me hope.

Aaron Bernstein

Interim Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Harvard C-CHANGE)

Climate change doesn’t scare me, and it need not scare anyone. To combat fear that grows from inaction and inadequate leadership, we must remind ourselves time and again that we have solutions to the climate crisis and that these solutions improve health today, especially for the poor and vulnerable, and that they provide for a more just and livable world for our children.

While much, much more needs to be done to put us on the right path to avert the worst effects of climate change, the growth of renewable energy around the world, the rise of electric vehicles, and the growing appreciation for plant-based diets all give reason for hope over fear.

When it comes to climate actions, it’s all too easy to believe that what we do as individuals doesn’t matter. How could one person’s deeds make even a tiny dent in the scope of global greenhouse gas emissions? For anyone who doubts our individual actions matter, look no further than what is happening in communities across this country right now. By keeping our distance from others, we have saved tens of thousands of lives, especially among the poor, older people, and those whose health is compromised. With COVID-19, of course, we have been asked (and in some cases commanded) to change our ways by our leaders. But a prevailing sense of responsibility to and pressure from our families and communities has led to more people doing what’s needed.

Our individual climate actions can have the same effect. As individuals act, we can create a path that many more will walk on. The good news about climate actions is that as they make the planet healthier, they also make us healthier, helping to solve problems like obesity and mental health disorders, which have exacted a huge toll on so many people.

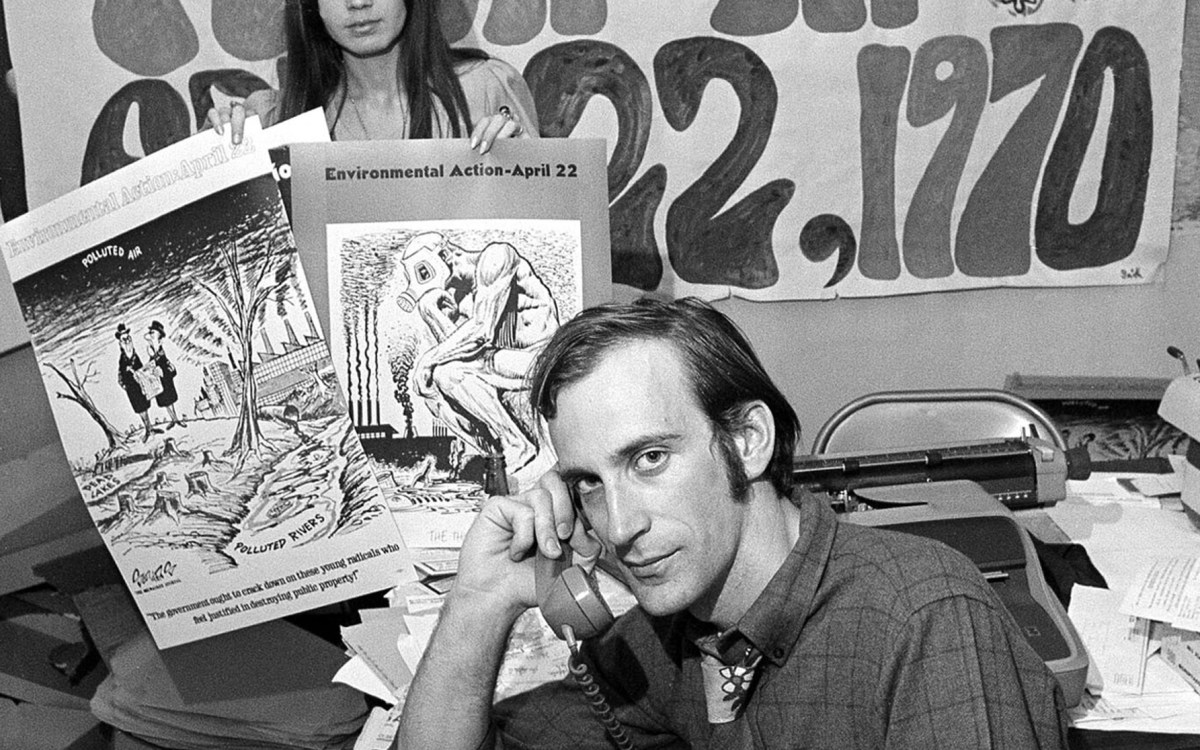

Fifty years ago, a small group of people organized many more to protect the world we live on. Their motivation came from a recognition that a polluted world was unviable not just for all the other life forms we share the planet with, but for ourselves. Their example and motivation matter today more than ever. We must act to protect the earth, its climate, and all the life we share it with because our lives, and the lives of generations to come, depend on it.

John P. Holdren

Teresa and John Heinz Professor of Environmental Policy at the Kennedy School of Government; professor of environmental science and policy, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences; affiliated professor, Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

The disruption of Earth’s climate by human activities scares me for many reasons. Here are three. First, climate is the envelope within which all other environmental conditions and processes important to human well-being must function. Those conditions and processes include those that govern the quality of air, the quality and quantity of fresh water, the fertility of soil, the productivity of the ocean, and natural controls on pests and pathogens. As our activities increasingly alter the climate — with direct impacts including hotter heat waves, stronger storms, bigger floods, larger wildfires, and inexorably rising sea level — we imperil all the essential environmental conditions and processes that function within the climatic envelope.

Second, the human activities driving the disruption of global climate are so deeply embedded in the economies of developed and developing countries alike that it is impossible to change the drivers rapidly. The biggest driver is the combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas — the fossil fuels — using technologies that discharge all of the resulting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In 2020, about 80 percent of the energy used by civilization worldwide still comes from these fossil fuels. It will take decades to free ourselves from them. The next biggest driver is land use and land-use change, including deforestation and many agricultural practices. These, too, in turn, are on such a large scale and driven by such fundamental forces in the world’s economies that they are very difficult to change quickly.

Third, impacts of global climate change are already causing serious damage to human health and safety, property, infrastructure, and terrestrial and marine ecosystems, even though the increase in the annually and globally averaged surface temperature has been “only” about 2 degrees Fahrenheit. At this point, because of the intractable nature of the drivers described above, it seems almost impossible to avoid an increase twice as large, which will result in a much more than proportional increase in the damages now being experienced.

The only good news is that public awareness of the ongoing harm and increasing danger is growing to the point that countries may finally undertake the remedial actions needed to avoid even bigger changes in our future climate, along with adaptation measures that can reduce the harm from the changes we cannot avoid.

Tyler Giannini

Clinical professor of law, co-director of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School, and founder of EarthRights International, an NGO that works to protect human rights and the environment

Giannini wrote his essay with his daughters Amaya Giannini (14 years old) and Rayna Giannini (10).

This is an intergenerational question, so the three of us sat around our dining room table and each made individual lists of how climate change scared us. Together, we represent one Generation Xer (aged 49) and two Generation Zs (aged 14 and 10) — also known as Zoomers. While our generations think differently on a lot of issues, what stood out most is that we have similar fears about climate change. We worry about the loss of ecosystems and about biodiversity. We worry about the future of humanity and our families, and we worry about how the world will react to the impending crisis. Will we come together or lose our empathy for one another? As the three of us started talking about our fears, though, we kept coming back to solutions — to listen to science, of course, but just as importantly to come together because tackling climate change requires seeing the connections between us rather than what divides us.

On all our lists, we hit on how we were scared of losing animals and hurting the planet itself. Climate change affects our ecosystems, and this will impact the lives of many animals. Some may even become extinct. But we also thought about how we are connected to our environment: Animals are a big part of our food chain, for example, and bees are critical pollinators, and if we lose them, it will affect our food supplies.

The theme of connection also played out as we talked about how climate change will deeply affect humanity. We fear for the unprecedented millions who will be displaced — the impending flow of climate refugees. We worry about our families, our kids, but we talked about how every displaced person is connected to a family. And we also know that it is much more likely that these families will be disproportionately poor and people of color, especially in the Global South.

We also worry about the emotional toll that climate change will take as we absorb a constant barrage of bad news — and how people will react once the impacts become even more serious than they already are. You can see how in the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, many thought it was far away and would not reach them. But there was a tipping point, and then it started to directly affect so many more people. This is where we are headed with climate change. Once we start treating climate change like the crisis it is, we hope many people will launch into action.

As we stay at home these days, we keep returning to parallels between climate change and the current pandemic. The curves look eerily similar. And there is a lingering question of whether we will hit the steep part of the curve or flatten the curve. For climate change, we fear hitting the tipping point and want to get ahead of it while we have time. In the end though, the three of us are most scared about what it will take to find solutions. It will take government action, individual action, and community action. Like the pandemic, we know it will take scientific knowledge and empathy and hope. We see the pandemic pulling us in two directions — increasing isolation and fears, but also creating innumerable acts of coming together and working to overcome the challenges. Solving the problem of climate change will not be successful if we allow our fears to overcome us. Solving the problem will require the strength, commitment, and creativity of our global community.

Robert N. Stavins

A.J. Meyer Professor of Energy and Economic Development, Harvard Kennedy School of Government

What concerns me most about climate change is the combination of a pair of its characteristics — one spatial and one temporal — that together make this an exceptionally difficult political challenge. Each of these characteristics takes us from the science of climate change to its economic realities and then to its very difficult politics.

First, greenhouse gases mix in the atmosphere, so the location of emissions has no effect on impacts — in economic terms, climate change is a global commons problem. It does not matter whether a ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions emanate from Cambridge, Mass., or Cairo, Egypt. They have the same impacts, and those impacts are spread globally.

However, any jurisdiction taking action incurs the costs of its actions (typically the costs of moving from reliance on fossil fuels to greater use of renewable energy resources, as well as increased energy efficiency), but the climate benefits of its actions are distributed globally. Thus, for virtually any jurisdiction, the climate benefits it reaps from its actions will be less than the costs it incurs (despite the fact that the global benefits may be greater — possibly much greater — than the global costs). This presents a classic free-rider problem, wherein it is in the interests of each country to do little and instead seek to rely on the actions of other countries. And this is why it cannot be left to individual countries to develop policies completely independently. Rather, international, if not global, cooperation is essential.

There is also a temporal dimension that takes us from science to economics to politics and policy. Greenhouse gases (GHGs) accumulate in the atmosphere (CO2 has a half-life in the atmosphere exceeding 100 years), and the damages are a function of the stock, not the flow of GHGs. Hence, the most severe consequences of climate change will be in the long term. But climate-change policies and the attendant costs of mitigation will be up front. This combination of up-front costs and delayed benefits presents a tremendous political challenge, since political incentives in democracies are typically for elected officials to convey benefits to current voters today, and place costs on future generations. The climate problem asks politicians to do precisely the opposite!

Together, the global commons nature of the problem plus this intertemporal asymmetry make climate change an exceptionally tough political challenge (and suggest why economics can help with the design of better public policies).