The way we live now

One College student adjusts to life on a deserted campus and another to being unexpectedly home a continent away

Barbara Oedayrajsingh Varma walks through Harvard Yard with Remy the cat.

Photos courtesy of Barbara Oedayrajsingh Varma

Barbara Oedayrajsingh Varma’s room in Eliot House looks a lot like it did three weeks ago, with textbooks on the bookshelf and photographs of friends and family covering the wall above her desk. But since the COVID-19 threat prompted the evacuation of campus and a shift to online-only classes, everything outside her door is unrecognizable.

Oedayrajsingh Varma, a junior from the Netherlands studying psychology, is one of several hundred students who remain on campus, owing to special circumstances. Instead of walking to and from classes, hanging out with friends in the House courtyard, and singing with Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum and the Radcliffe Pitches, she attends her four classes online and checks in with friends over Zoom, text, and outside (from a safe distance). The familiar has become strange, a problem that many share, even those who returned home.

“I was really scared that I was going to be constantly reminded what life would have been like if the pandemic hadn’t happened,” said Oedayrajsingh Varma. She noted that her three roommates left campus and that she eats take-out meals from the dining hall in her room or outside, a big contrast to the usual dining with friends.

Deciding to stay was not easy.

“There was a huge spread of the coronavirus in the Netherlands, so staying [at Harvard] was not great, but going home was also not great,” she said. “It was very difficult to make the choice, and having to consider factors like [the U.S. ban on travel from Europe] was a very, very strange experience.”

Like other international students, Oedayrajsingh Varma faced uncertainty around maintaining her visa status, eligibility for work authorization, and the ability to return if she left the U.S. To help deal with these issues, she sought guidance from the Harvard International Office.

Barbara Oedayrajsingh Varma finds a friend in Remy. Her room in Eliot House looks much like when she moved in, minus the roommates.

And now she is puzzling out how to make it work. “I tried very hard to build myself some sort of semblance of a routine, despite all the chaos,” she said,

That routine includes more mindfulness and yoga practice, as well as long walks around parts of Cambridge she had not gotten around to exploring. Oedayrajsingh Varma also plans to continue building community as co-president of the Harvard Woodbridge International Society, despite the dispersal of students around the world.

“Time zones make things more complicated,” she said. “We’re trying to figure out how to have fun events online and more practical panels about adjusting to life off campus.”

Oedayrajsingh Varma worries about her family at home and being unable to travel to see them. The uncertainty of summer plans also looms. But she is optimistic about what will happen next.

“I hope that having this experience right now will make me enjoy [life] even more when we eventually return and are able to be together with our friends and be in a physical community again,” she said.

******

Three thousand miles away in Pico Rivera, Calif., Andrew Pérez returned home from Harvard to finish his senior year. He quickly adapted his schedule to Pacific Daylight Time and an active household that includes seven other people, two of whom are his school-aged nephews.

Being in his hometown southeast of Los Angeles has given Pérez time and distance to reflect on being a first-generation student coming to, and then abruptly leaving, Harvard.

“There are a lot of emotions attached to leaving a place that has been home to me,” said Pérez, a sociology concentrator. “It felt like I had been [at Harvard] forever, but I’d also just gotten there. That made me realize how large of an impact the institution has had on me, and that I’m deeply saddened to be away. I feel as if I don’t have the closure of ending such an incredible experience.”

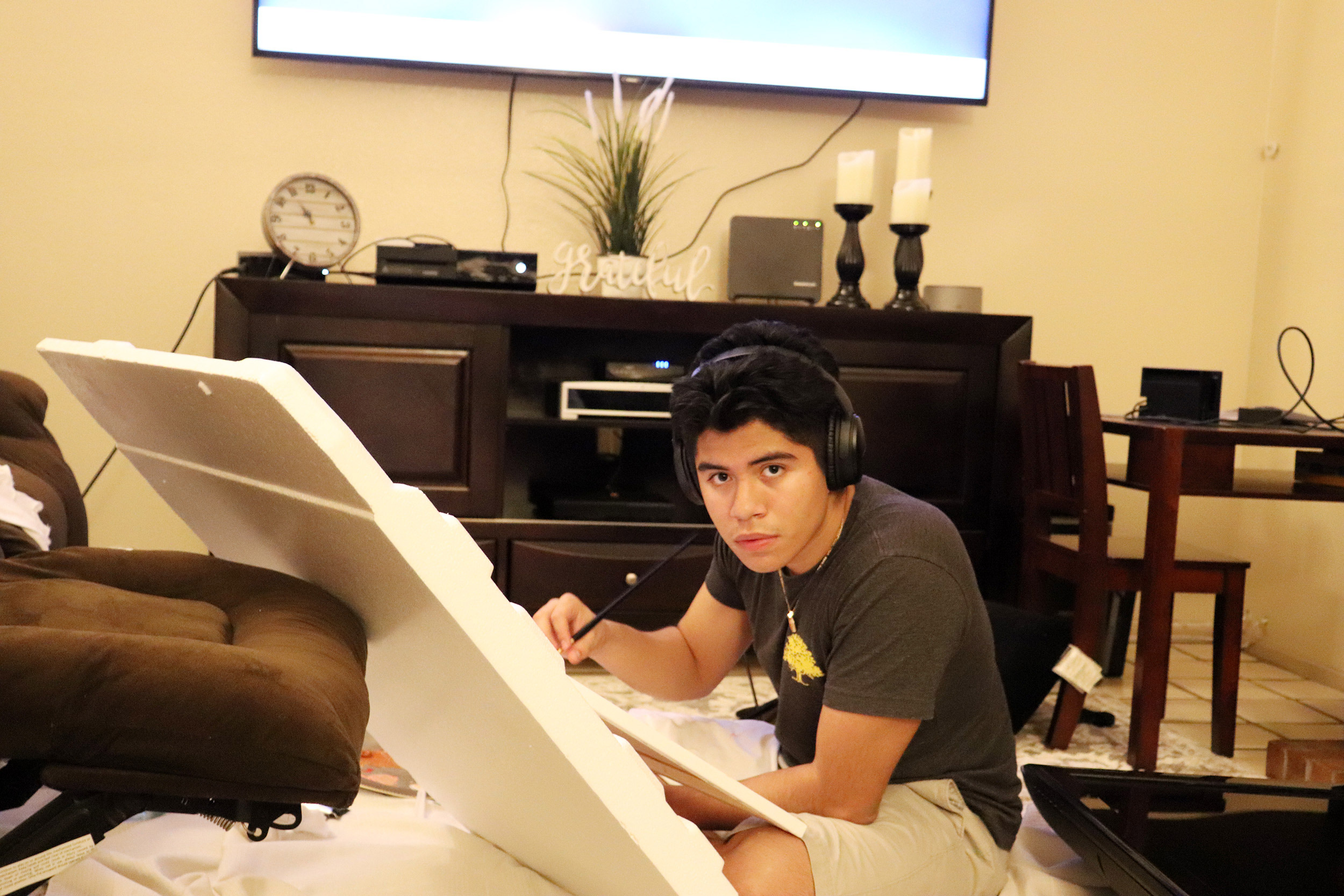

Andrew Pérez returned to his home in Pico Rivera, Calif., where he was finishing up a painting assignment for the class “Painting’s Doubt.” He chose to paint his older nephew, Jadon, 11. The younger nephew, Matteo, 4, watches the process.

Photos courtesy of Andrew Pérez

The move-out period before spring break was sudden and harried. In addition to packing and wrapping up assignments, he worked extensively with Primus, a student-run organization serving first-generation students, to disseminate information about travel expenses, storage, shipping belongings, and other resources.

“When I heard the [evacuation] news on March 10, I was in shock. I was trying to figure out what this meant for low-income students, and about where my sources of income were going to come from,” said Pérez, a Mather House resident who had on-campus jobs at the Harvard Kennedy School Library and as a course assistant in sociology.

At the same time Pérez was helping other students deal with the uncertainties of the pandemic, he said goodbye to his roommates, House, and mentors during the Mather senior send-off and squeezed in late nights with friends.

“Seeing everyone come together, whether it was faculty members who wanted to help, or alumni from across the globe, or fellow students who had more privilege and access to resources, was powerful,” he said, pointing to fundraising by the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Foundation at Adams House and the First-Generation Harvard Alumni and a crowdfunding campaign that together raised thousands of dollars for students. Pérez is now working with FGHA to help distribute $65,000 in grants to first-generation, low-income students. “[It] reminded me of how special a place this is and how much we all look out for one another and want to see each other succeed,” he said.

Pérez had planned to bring his family to campus for Commencement, which would have been the first time everyone in his household would have seen where he lived, worked, and studied. Instead, he brought Harvard home in a way he never expected.

“In a way, I’m able to bring my educational experience to the rest of my family,” said Pérez. “As a first-gen student, my parents have always been confused about what I study and what I do. Whenever I’ve been home in the past, it’s always been on vacation, so they’ve never seen me do schoolwork. So now they are going to be able to see what my education actually looks like.”

During the first weeks back in classes, Pérez’s life at home included early morning Zoom meetings of “Leading the Profession: Teacher Empowerment and Activism,” a course at the Graduate School of Education, setting up his art supplies for the Gen Ed course “Painting’s Doubt,” catching up with friends over the House Party app, and going running with his 11-year-old nephew, whom he promised to take to Yosemite National Park if they run together until Pérez’s “virtual graduation.”

“I think the people who can get the most out of this experience [while I’m home] are my nephews, seeing my work and asking me questions. We can begin to have those conversations,” he said. “Being at Harvard reminded me that the world is a lot bigger than just me and my community in L.A., and there are a lot of privileges that come when you go to a place like this, but it’s my obligation to give back to those people who didn’t have access to Harvard. There are so many other kids who are just as special and talented but didn’t have the resources or access to get [here]. [That pushes] me to be a better person and a better citizen of the world.”