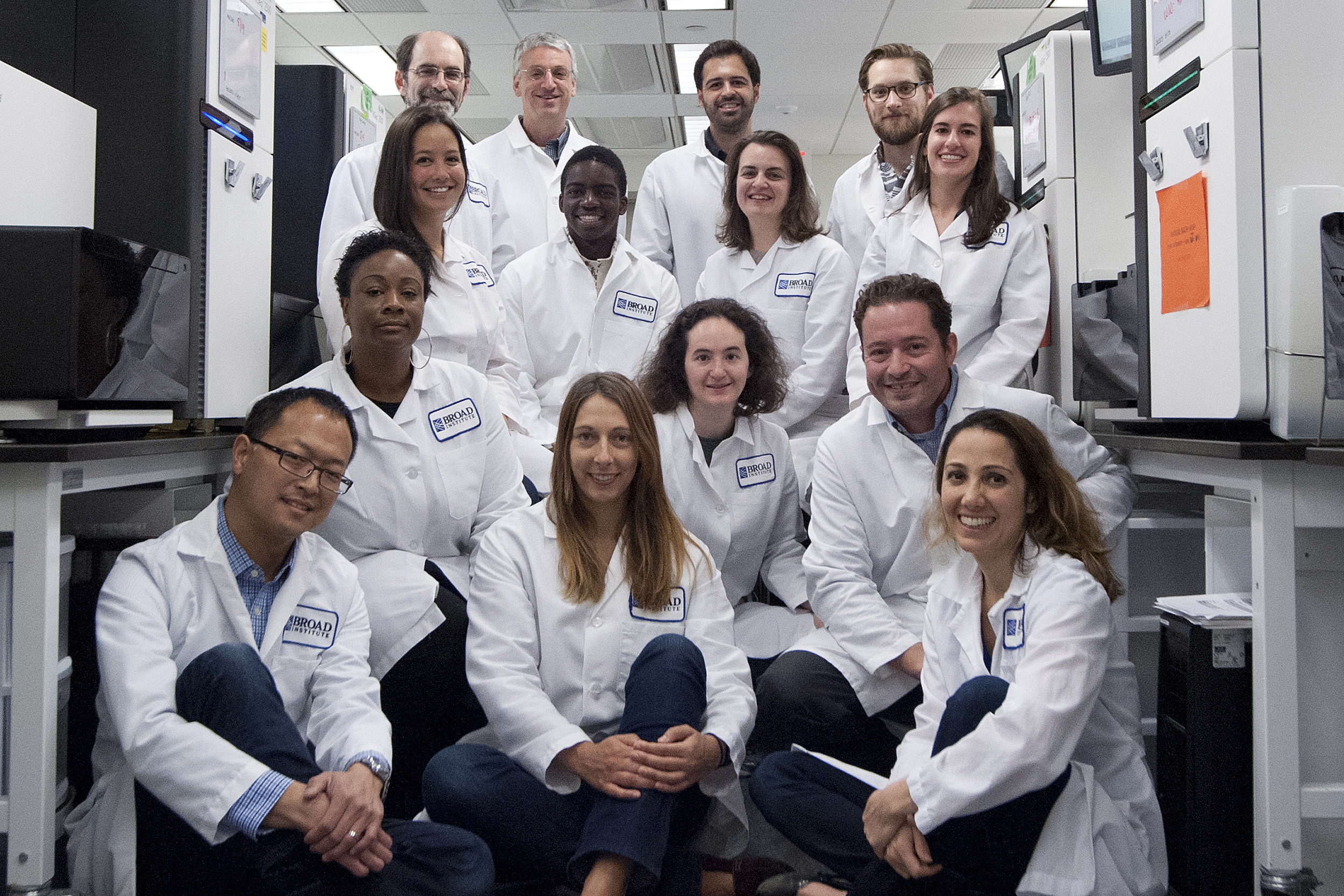

The Sabeti Lab Broad sequencing team at the Broad Ilumina Miseq facility. In 2015, the team sequenced the Ebola virus genome.

Photo by Michael Butts

Responding to this pandemic, preparing for the next

Pardis Sabeti is in great demand, and her work seems prescient. She might say that’s only because we haven’t been paying attention

By the time computational geneticist Pardis Sabeti finishes breakfast these days, she knows her inbox will be stuffed with notes, questions, and responses, all of which will require her immediate attention.

There’s a thread on the diagnostic tests her lab at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard are developing for a range of diseases, now including COVID-19. Another scroll and there’s a back-and-forth she needs to weigh in on about the genetic sequence of the novel disease. There are also conversations on a project, eight years in the making, to help West and Central Africa detect disease threats as they emerge, a kind of pandemic early warning system that feels wildly prescient to the uninitiated.

Then the meetings start.

“I’m in meetings all day, every day from 7 a.m. till midnight, basically, and then working through the night,” said Sabeti, a professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “It’s been a marathon.”

Since early January, work has meant 16- to 18-hour days, seven days a week for Sabeti, who uses algorithms to study genetics and is perhaps best known for her research on infectious diseases and her genome detective work sequencing the Ebola virus in 2014 during the outbreak in West Africa. Her already-urgent projects have intensified in the age of coronavirus, which has itself spawned new emergencies.

Right now she is working to set up and scale COVID-19 testing in the Boston area, helping hospitals in parts of Africa do the same, and sequencing viral samples from Massachusetts patients. The pandemic has revved up existing projects, like the African surveillance system and a new CRISPR diagnostic test her lab developed with MIT.

Underlying it all has been a single, consistent goal: help the world respond to the latest disease threat while preparing it to do better on the next one.

“Our goals are finding ways of detecting these microbes, connecting that information and sharing it in real time, and empowering every actor — from the researchers and the clinicians to the average citizen — so they can be best informed and best able to respond in the context of the outbreak,” said Sabeti, who is also a professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, an institute member at the Broad, and a Howard Hughes Investigator.

She’s been committed to this kind of work for a while. After studying biology at MIT, in 1996 Sabeti won a Rhodes Scholarship to study genetic resistance to infectious diseases at Oxford University, where she focused on malaria. Before she graduated Harvard Medical School in 2006, she had developed an algorithm and a tool that helped scientists mine the human genome for regions linked to infectious disease. In the process, she began studying Lassa fever, which causes a hemorrhagic illness similar to Ebola. When the Ebola epidemic began in West Africa in 2014, Sabeti was part of a team that diagnosed the first cases in Sierra Leone and sequenced the virus’s genetic makeup. The team discovered that the epidemic started with a single transmission from animal to human and from there spread person to person.

Pardis Sabeti and Christian Happi (right), director of the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases and a professor of molecular biology and genomics at Redeemer’s University, in a lab at Redeemer’s University in Nigeria.

Photo by Alwyn Marx

For that effort, she was named one of Time magazine’s Persons of the Year and made its list of the 100 most influential people in early 2015. She’s won a host of awards for other genetic-related work, including a Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award for Natural Science.

“She’s one of the leaders in the field,” said Dyann F. Wirth, the Richard Pearson Strong Professor of Infectious Diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who’s worked with Sabeti on projects since 2005. “She’s a brilliant scientist and is driven to do the best science for the most important public health problems.”

Sabeti was born in Tehran in 1979 to parents who fled the Iranian revolution, and today she oversees a 50-person lab at the Broad that focuses on researching infectious diseases, monitoring currently circulating illnesses, and keeping watch for new ones. Her group took note when the novel coronavirus popped onto the radar in December. After Chinese scientists published the virus’s genetic sequence on Jan. 10, the Sabeti Lab sprang into action to make sure their partner sites were prepared to test for the fast-spreading disease.

“We ordered reagents and [our clinical fellows and postdocs and trainees who go there regularly] brought them to our field sites in Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria,” Sabeti said. “Then as soon as cases started happening in the United States and when the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and [Food and Drug Administration] allowed for hospitals to set up lab-developed tests, we partnered with Eric Rosenberg, Sarah Turbett, and their amazing team at [Massachusetts General Hospital] and worked together to stand up a lab-developed test in the clinical lab and then to scale capacity.”

Sabeti in a village in Sierra Leone where she conducted community outreach.

Photo by Erica Ollman Saphire

MGH rolled out its coronavirus test on March 13. It is believed to be the first hospital in the state to do so, said Rosenberg, director of MGH’s Clinical Microbiology Laboratory and a professor of pathology at HMS. He said Sabeti and Jacob Lemieux, a postdoctoral researcher in her lab, helped the hospital design its test, which evolved from a system capable of processing 20 to 30 samples per day to one that can do 500 to 600.

“[Pardis and Lemieux] came over to our lab, shared their expertise in regard to how to rapidly stand up this type of diagnostic assay,” Rosenberg said. “MGH could not have developed or scaled up testing without them.”

“Diagnostics and surveillance, in general, is fundamental,” said Sabeti, whose lab is now working with other area hospitals to scale their testing. “With testing, you can isolate, you can stop it from spreading, and you can identify individuals who need to be treated. It is that critical situational awareness you can’t do anything without.”

It’s why she’s been among dozens of experts who have advocated for better early detection tools and increased testing to combat the spread of infectious diseases. It’s also why she was tapped as the co-lead for the diagnostic working group at the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness in late February.

“Pardis Sabeti is a remarkably creative physician-scientist who’s built rapid-diagnostic tools critical for monitoring outbreaks of infectious diseases like Zika, Ebola, and even mumps in our local college communities,” said Harvard Medical School Dean George Q. Daley, who heads the consortium. “Consequently, she was the first person I emailed in January when the virus was raging in Wuhan and threatening to become pandemic.”

The consortium’s goal is to rally the region’s biomedical science talent to develop better diagnostics, therapeutics, and potentially a vaccine for COVID-19. As part of the group, Sabeti has been helping track the players developing new diagnostics and helping them get what they need, like reagents and samples, to move their efforts forward.

At her own lab, her team just unveiled a new CRISPR-based test, developed in collaboration with a team at MIT, that offers same-day results. The test uses microfluidic chips that can scan one sample for more than 160 different viruses simultaneously instead of one at a time. It can also perform more than 1,000 tests at once looking for a single type of disease. The team hopes the diagnostic can be used someday to rapidly characterize an infection within a population.

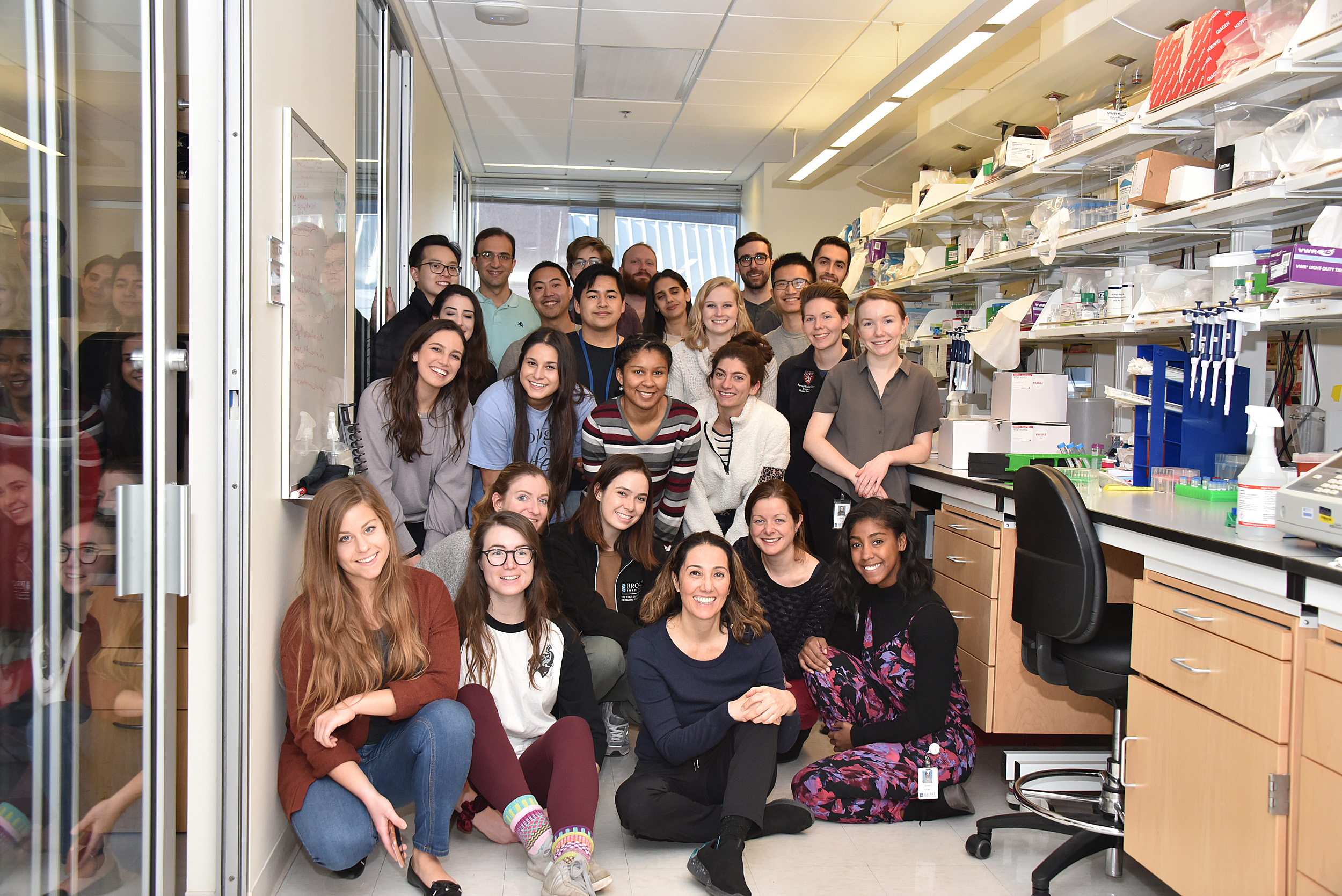

The Sabeti Lab team during Lab Cleanup Day at the Broad last year.

Photo by Michael Butts

“For us, it’s really important that if you’re going to respond to a pandemic, you should create things that can be stood up very, very quickly,” Sabeti said.

Sabeti is working with the Massachusetts Department of Health and MGH to sequence viral samples taken from COVID-19 patients in the state. The goal is to figure out what story the Massachusetts sequence is telling about patterns of transmission or how the virus is evolving.

Sequencing a virus essentially means reading out every letter in its genome to get a full blueprint of what makes the virus what it is. “It’s a barcode,” Sabeti said. “It immediately tells you what you’re looking at. What you’re dealing with.” It’s what’s used to create tests, treatments, vaccines, and what helps epidemiologists understand the origin of the virus and how it’s spread.

“You can use it to try to investigate things like if particular mutations in the virus impact clinical outcomes or if you can shed light on how the virus is spreading within particularly communities, like among health care workers. There’s a number of important questions you can ask with that kind of data.”

The lab plans to share its data and findings as soon as possible, a hallmark of Sabeti’s practice during a crisis. It is, for instance, what her group did online in 2014 right after sequencing the Ebola samples.

“Apparently, it was not done previously,” Sabeti said. “To us, it was intuitive. We were surprised by how revelatory it was. But you can’t hold data in the middle of an outbreak. I mean, it wouldn’t make sense. Especially, the kind of data that is critical to response.”

“Everyone anywhere in the world is experiencing what it means to be in an outbreak. … The only one possible positive outcome is that the world finally takes this seriously.”

Pardis Sabeti

At the same time, the lab is mindful of the misinformation that can spread when data is released before being vetted. “It is important to share results fast, but they have to be right; they have to be rigorous,” Sabeti said. “We have seen how disruptive it can be when people release data that is not ready.”

In the past, Sabeti’s lab has also worked with the Massachusetts Department of Health to run CDC-funded training programs in genome sequencing of infectious diseases. The lab has also worked to create an outbreak simulation program similar to war games, which is used by high schools in the U.S. and China. “Education is a really big part of what we do,” Sabeti said.

The lab started working in West Africa in 2008 when it started collaborating with medical facilities in Nigeria to study Lassa virus. The group then established programs in nearby countries like Sierra Leone to track different viruses circulating in the area and understand their biology through genomic research. Sabeti’s work helped establish the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Disease in 2014 at Redeemer’s University in Nigeria.

Through the center, they’ve been able to teach nearly 1,000 people from Western and Central Africa and even Southeast Asia and Europe how to apply genomic technology to infectious diseases.

One of their biggest undertakings with the center is Sentinel, an early warning system that can detect and respond to emerging viral threats in real time. The plan is to combine rapid CRISPR-based test results in different regions and countries with data-sharing technology to track outbreaks and share information to preempt a pandemic.

The project just received funding from the Audacious Project, a bold initiative housed at TED. The hope is to deploy Sentinel in West and Central Africa, then expand it around the world.

Pardis Sabeti gives a presentation on her work at TEDWomen 2015.

Photo by Marla Aufmuth/TED

Sabeti has had her sights set on a system like this for the better part of the last decade, especially now seeing what’s happened with the coronavirus response.

“For a very long time, we’ve had the technology and the capacity to do better,” she said. “All the tools have been there. They just have to be put together and supported. That is the part that hasn’t [completely] happened.”

The world is paying attention now, she added. Maybe things will change.

“Everyone anywhere in the world is experiencing what it means to be in an outbreak and while I hate that and hate the tremendous amount of suffering that’s happening because of what we have to do in response to this,” Sabeti said, “the only one possible positive outcome is that the world finally takes this seriously.”

For now, Sabeti plans to keep running her marathon.