Photo illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

The COVID-19 evacuation wasn’t Harvard’s first

The University’s history of upheaval in war and peace, contagions and contaminated puddings

The evacuation of campus two months ago due to the mushrooming coronavirus outbreak was a jarring if orderly affair. But then, it turns out, Harvard has had significant and varied experience with upheaval.

In 1775 George Washington’s Continental Army occupied the campus, and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety ordered Harvard to vacate its grounds. Professor Joyce Chaplin reminded her students of that earlier crisis during their last on-campus class on March 11 as a way to offer some comfort by putting the move to distance learning into a historical context.

“I wanted to try to reassure students that this was not unprecedented,” said Chaplin, the James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History. “The assumption was that Harvard had never had to do this before.” And other experts of the period note that not only has Harvard faced other trials, but the one in the early days of the Revolution left many students then with a renewed sense of commitment to make a difference.

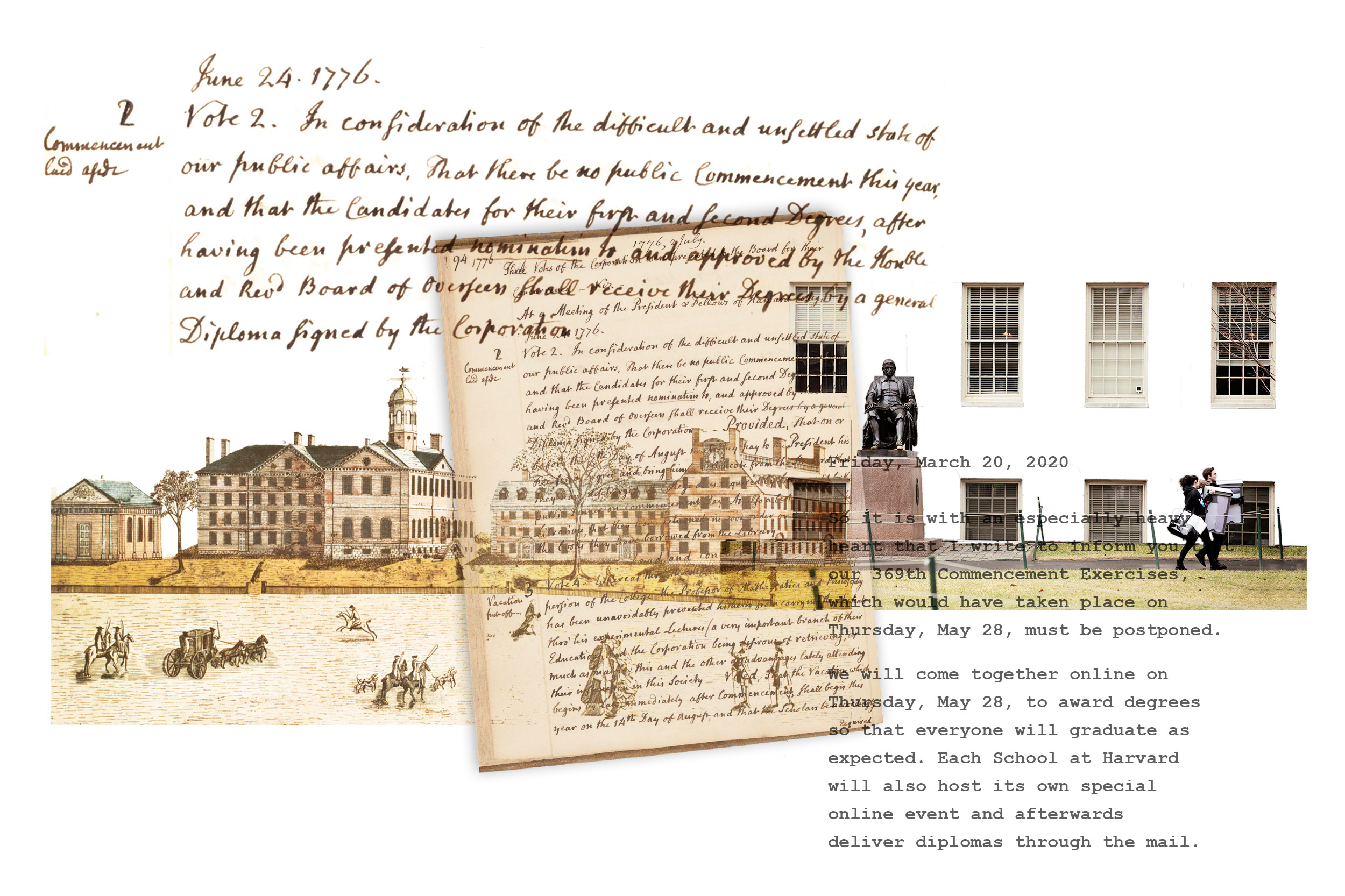

In that earlier evacuation students were told to leave the campus on May 1 and move to nearby Concord, where they stayed for eight months. Commencement was postponed “in consideration of the difficult and unsettled state of our public affairs,” according to records of Harvard’s Board of Overseers from that time. Students reconvened in Cambridge on June 21 the following year.

This year, March brought similar changes. As the threat from COVID-19 rose globally in the first part of the year, the disease drew inexorably closer until reaching the Boston area. Before it struck hard, but when it became clear it would, Harvard decided to conduct the rest of the semester remotely through digital learning. Students shortly left for spring break, but this year not to return. Faculty had about 10 days to pivot their teaching toward online platforms. Staff members had to adapt to doing their jobs remotely, or to add masks, gloves, and caution to their campus routines if they were essential personnel.

For a major university, these were lightning-quick changes. But in the weeks to come, the internet systems held strong, professors taught, students learned, and Harvard continued its mission, to the point of having its graduation ceremony, this year called “Honoring the Harvard Class of 2020,” online this Thursday morning. The program begins at 10:30, with the ceremony starting at 11. A grander, in-person celebration of the class will await safer times.

Harvard has weathered other disruptions during its long history, though they were more common in the University’s early years, said Zach Nowak ’18, a College Fellow at the History Department.

In 1639, Harvard shut down for a year after Nathaniel Eaton, the School’s first head, was fired over allegations that he’d severely beaten students and that his wife had served them spoiled fish and hasty pudding that had somehow been laced with goat dung.

Professor Joyce Chaplin shared other abrupt student departures in Harvard’s history.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

“There are periodic student rebellions,” said Nowak, who taught the class “Intro to Harvard History: Beyond the Three Lies” last fall. “Most of these rebellions are set off by bad-quality food, but the ultimate causes are a really boring curriculum in Latin and Greek, a strict discipline, and a very paternalistic system. Remember, there were kids who were 12, 13, 14 years old going to Harvard in the 1700s.”

Smallpox and diphtheria were public-health crises in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1752, a smallpox epidemic shut down Harvard for five months and canceled Commencement for that year.

For historians, it is too early to know how the coronavirus pandemic will be remembered in Harvard’s records. “We are probably pretty early in the pandemic, though, so there is no way to be sure of its long-term consequences,” said Conrad Wright ’72, Sibley Editor at the Massachusetts Historical Society. “Only when it is in our rear view will we really be able to take its measure.”

Historians hope students will learn from their counterparts who lived through the first student evacuation. Students from that era showed greater interest in government and public service than their predecessors or those who came after them. The end of the war and a new federal government provided new opportunities to hold office and serve, Wright said.

In 1775 Commencement was postponed “in consideration of the difficult and unsettled state of our public affairs.”

Harvard’s Board of Overseers

“I certainly think that many Americans, and certainly Harvard men, felt an obligation to serve following the war,” said Wright. “Speaking of today, I’m reminded of one of my daughters, who is in her second year of medical school. I’ll be willing to bet that for many people at her stage of training, careers in public health are going to seem very appealing. Circumstances, opportunities, and training can go together to influence the courses people follow.”

On her last class on campus on March 11, Chaplin walked by the Widener Library, where the Class of 2020 was having their class picture taken, and felt a mix of emotions.

“I remember saying to my colleague, ‘This is very sad, but they are going to have an epic class reunion when they come back,’” said Chaplin. “They will have an amazing story, and amazing grounds for solidarity.”