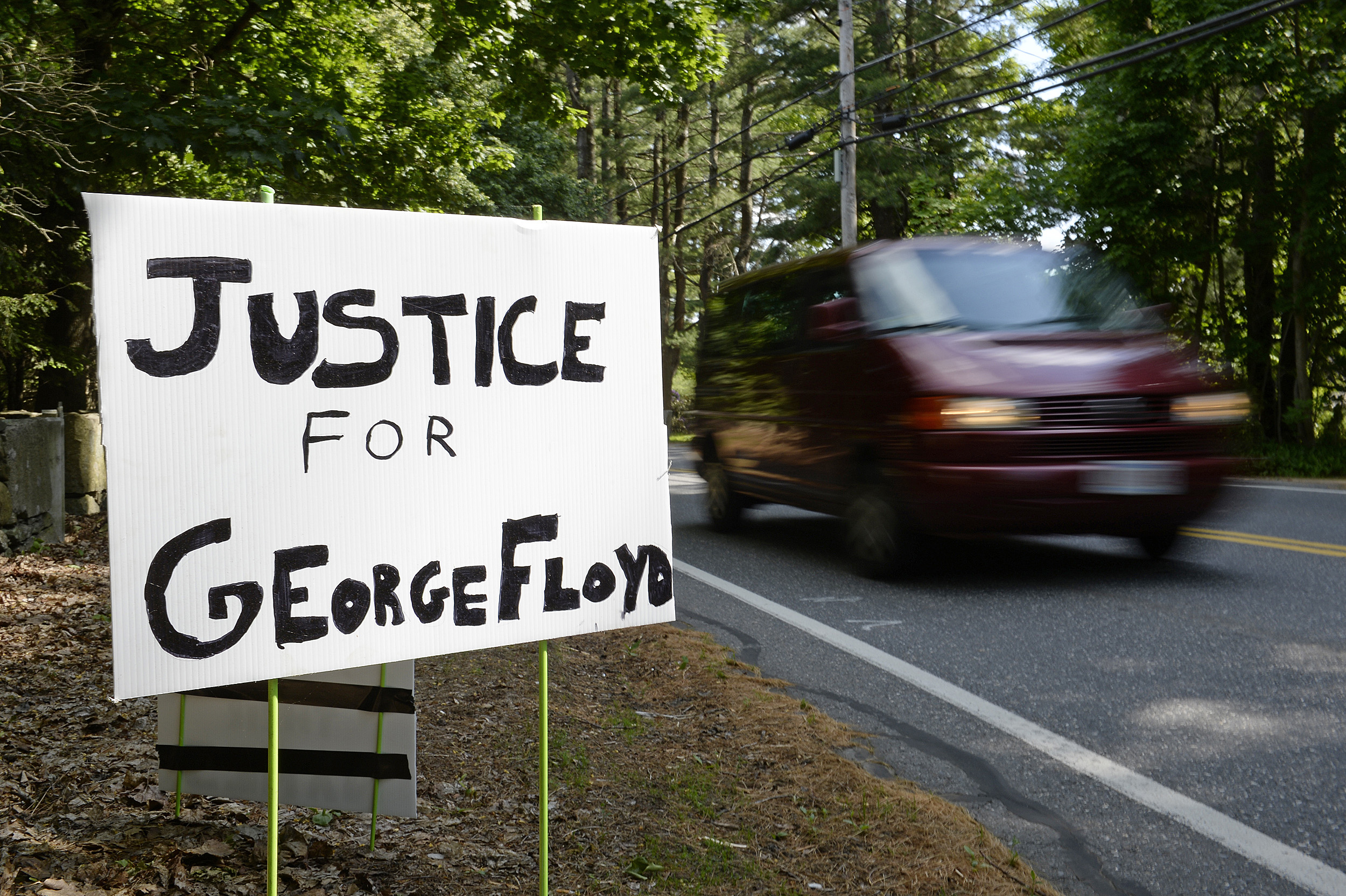

A roadside sign seeks justice for George Floyd, whose killing by Minneapolis police set off protests worldwide.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Facing the denial of American racism

Radcliffe Institute panel explores its social roots and explores ways to raise awareness

As ongoing nationwide protests illustrate, a majority of Americans view the recent police killing of George Floyd as a reflection of the virulent and systemic racism in the nation. However, recent polling suggests that denial of the underlying issues still exists, complicating the search for solutions. To tackle this problem, the Radcliffe Institute on Thursday hosted “Naming Racism,” an online discussion focused on identifying the historic and ongoing social roots of this denial and discussing strategies for raising awareness.

Radcliffe Institute Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin introduced the discussion between Camara Phyllis Jones, the 2019–2020 Evelyn Green Davis Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute, and David R. Williams, Frances Sprague Norman and Laura Smart Norman Professor of Public Health and chair of the department of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Brown-Nagin said that the talk originally was envisioned as an examination of the racial disparities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. But given recent events, the institute decided to pivot to a broader discussion of how deeply embedded racism is in American life. “We must reckon with this reality before we begin to move ahead,” she said.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, introduced the virtual seminar. “We must reckon with this reality [of racism] before we begin to move ahead,” she said.

Opening the discussion, Jones used an anecdote from her years in medical school. Going out to eat after a long night studying with friends, she noticed a sign on the door that had been flipped so that, sitting inside, she faced the side that said “open.” Seated inside, she and her friends could eat. But the people outside the door — who would see the sign as “closed” — could not.

“I recognized that other hungry people, just a few feet away but on the other side of that sign, would not be able to come in and order their food and eat,” she said. That dual reality epitomized racism. It also clarified the choice. If you are eating, she said, you might not be aware at first of those who are locked out. That, she explained, is a state of privilege, an insular view that does not look beyond itself.

Awareness, she stressed, is only the first step. Once aware, she asked, how will you react? You might talk to the restaurant owner, asking for those people to be let in. You might pass food out the window or even tear down the sign. “But at least you won’t be saying … I wonder why those people don’t just come in and eat,” she said. “Racism is a system … of structuring opportunity and assigning value on a social interpretation of how one looks.”

“When you lack empathy for a population, you don’t feel their suffering, and you do not support policies to … address the challenges the population faces.”

David R. Williams

Simply getting people to recognize that others are excluded is difficult, said Williams, who is also a professor of African and African American studies and of sociology. He said many Americans underestimate racial inequities, and some among those who are aware of inequality blame minorities themselves. Citing national data from 2015, he said that 50 percent of white Americans believe that discrimination is as bad against whites as it is against people of color. In addition, while a majority of Americans seem to understand that hard work does not guarantee success, a full 50 percent of whites believe that people of color would be more successful “if they only tried harder.”

Such beliefs are taught early. Williams said studies show that at the age of 5, children express the same degree of empathy when they are shown pictures of people both white and black being pricked by a pin. However, by the age of 7, they begin to believe that the white person feels more pain, and by the age of 10 the bias is “pronounced and stable.”

“When you lack empathy for a population, you don’t feel their suffering, and you do not support policies to … address the challenges the population faces,” he said.

Such callousness and indifference have kept alive racist institutions and structures such as residential discrimination — notoriously, redlining housing developments to discourage black buyers — detailing how it has continued to adversely affect everything from economic prospects to longevity, Williams said. “I like to think of residential segregation as the secret sauce that drives and produces racial inequality in the United States,” he said. “Your ZIP code is often a more powerful indicator of how long and how well you live than your genetic code.”

If anything, added Jones, recent events have underlined the generational effects discrimination has had on the health of people of color. The COVID-19 pandemic, she said, is “pulling the sheets off U.S. racism.” At the same time, she said, police killings of black people are “putting in your face the fact that our lives are not valued, that we’re not even considered human.”

To move forward, Jones said, organizations “have to be committed to naming racism.” Then, she added, we can strategize to act.