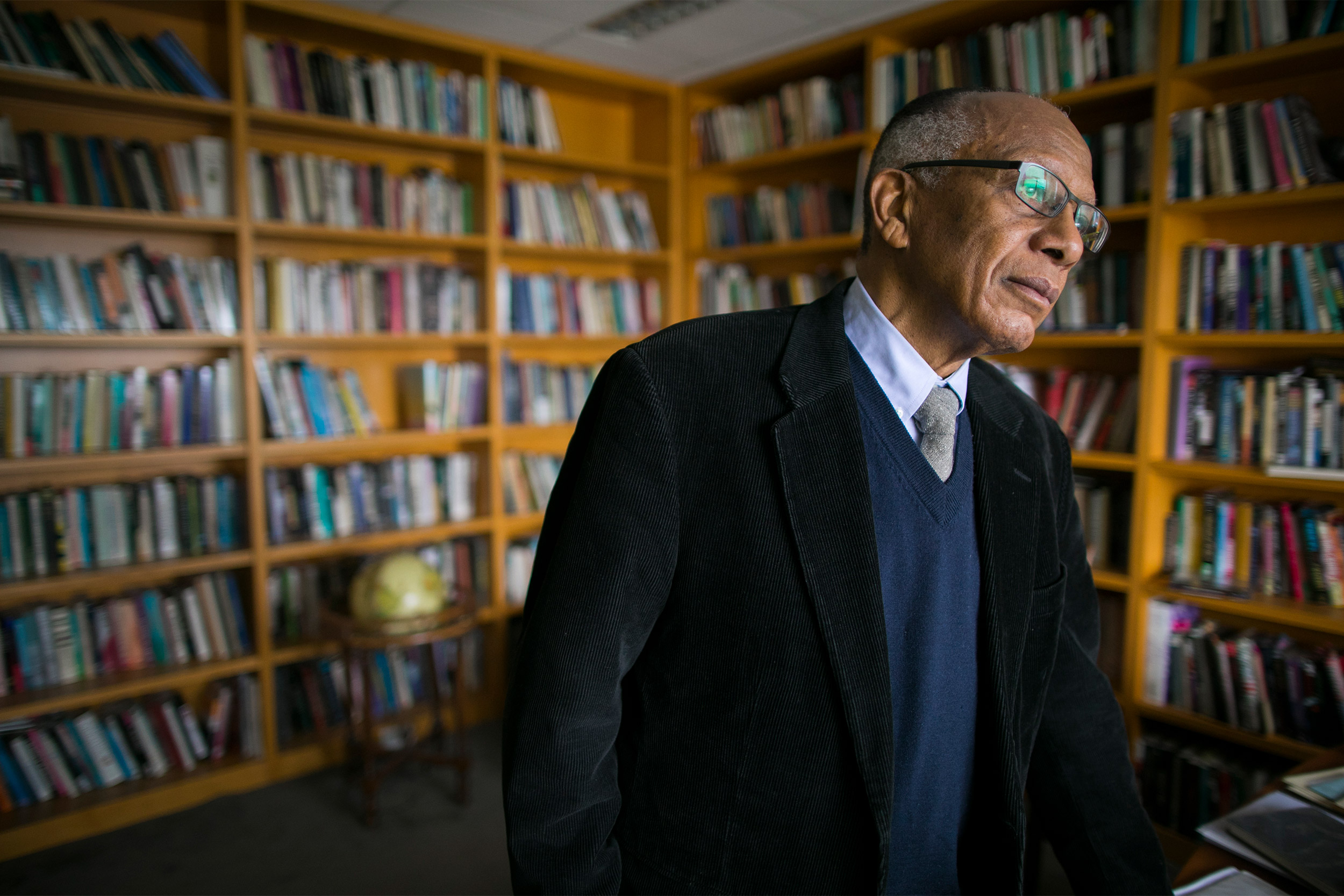

A scholar of slavery and issues of race, Orlando Patterson, the John Cowles Professor of Sociology, talks about the killing of George Floyd.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Why America can’t escape its racist roots

Orlando Patterson says there’s been progress, but the nation needs to reject white supremacist ideology, bigotry in policing, and segregation

The killing of George Floyd, who died after a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled into his neck for nearly nine minutes during an arrest, has spurred a wave of rage, anguish, and protests across the country. To better understand what is happening and what the future may hold, the Gazette talked with Orlando Patterson, the John Cowles Professor of Sociology. A scholar of slavery and issues of race, Patterson talked about the legacy of white supremacist ideology, racism in policing, and the ongoing, widespread discrimination and segregation in American life. He also explained why he hopes that the country can yet heal its racial divide, and sees particular promise in the young.

Q&A

Orlando Patterson

GAZETTE: Two years ago, you spoke to the Gazette on the 50th anniversary of the Kerner Report, which blamed white society’s racism as the underlying cause of the race riots of 1967. You said then that maybe we needed another report that looks at the roots of the racial inequities in the country. What is your take now?

PATTERSON: Reports are always useful if well done. There are now many studies of race and inequality, in fact it’s a virtual industry. There’s no shortage of thorough and well-informed research. But it would do no harm to have a group of people bring together the main results of the findings of recent studies, as well, including the views of influential people, not just academics, but also community, political, and religious leaders, who can say where they think we are and where we are going in terms of race relations in America. That’d be important especially now, after the killing of George Floyd. Many people must be asking themselves what has happened over the past half a century or more, since those first set of defining riots of the ’60s, not to mention the Rodney King riots in 1992. Is the element of white supremacy and chronic racism so deeply rooted that no amount of not just protests, but reform and institutional change is going to make a difference? That’s a depressing view. My sense is that there’s something new in these demonstrations.

GAZETTE: What is new about these protests, compared to the protests of 1967, 1968, or 1992, or the more recent ones organized by the Black Lives Matter movement?

PATTERSON: For one thing, and this is even true of the Rodney King demonstrations in 1992, the difference is the composition of the demonstrators. One cannot help but be struck by the significant proportion of the protesters who are white, Hispanic, and Asian. It was interesting, for example, that when the police brutally broke up a demonstration near the White House and trapped protesters on a road, a South Asian man took 70 of them in his house. My sentiment is that this is a more diverse, although still predominantly Black, expression of outrage. I think it has to do with the moment we’re living right now. People seemed horrified that we’re seeing this sort of thing after all these years, but they also sense that something is profoundly wrong. What’s terrifying about this moment is that the foundational institutions of our democracy are under assault, that the fundamental norms upon which our Constitution and our system of government rests are being threatened.

GAZETTE: What similarities do you find between previous protests, including the ones that followed the Rodney King beating, and the ones led by the Black Lives Matter movement, and the current protests?

PATTERSON: The common denominator is police violence and brutality. We have these brutal acts and killings, and we have outrage, protests, commissions, recommendations, and again and again, the police still continue in their old ways. They don’t seek to respect life and are prepared to brutalize someone for something as minor as passing a counterfeit $20 bill or jaywalking. The police are also very much part of one of the worst recent developments in American life: mass incarceration. It’s historically unprecedented, and it’s shameful that the country that claims to be the leader of the free world, although most of the rest of the world will consider that a joke, has the world’s highest number of people in prison: 2.3 million. And over 40 percent of those in prison are Black. This is really just astonishing, and the police have a lot to do with it, as well as prosecutors.

GAZETTE: There have been other cases of police brutality in the past few years, but why do you think the killing of George Floyd has led to this wave of protests even beyond the United States? Why did it happen now and not before?

PATTERSON: First, the whole thing was captured on video. And it was especially chilling because of the nonchalance, the sense of complete indifference, the disdain for someone’s life that the police officer showed as he killed Floyd. We have seen videos of brutality in the past, but this one came right after a series of police killings, and it simply reached the breaking point. When I saw the expression in that officer’s face and that three other officers were around him standing by as if this was just business as usual, I thought of Hannah Arendt and her phrase “the banality of evil.” What Arendt found most horrific was that ordinary people were able to commit horrible killings, and at the end of the day, they went back home to their nice homes and their nice families, and the next day they went back and killed again. I also think that the video came up in the midst of a pandemic, when people were feeling appalled at the incompetence and absence of leadership.

GAZETTE: What role might the pandemic have played in this wave of unrest?

PATTERSON: When we passed that critical milestone of 100,000 deaths, that called for a leader to express our collective fear and anxiety. We didn’t get that. People were really aghast at what was happening and at the reports that say that thousands of lives could have been spared if our leadership would have been more competent and less self-absorbed and concerned solely with the problem of reelection. The nation saw two big failures coming together: on the one hand, the absence of a proper health system and, on the other hand, the incompetent leadership. When the issue of police brutality came up with this video, people saw a link between the incompetent leadership, the failure of the American welfare state, and the resurgence of one of the worst aspects of American society: its white supremacist and racist ideology.

GAZETTE: How does white supremacy fit into this?

PATTERSON: What the killing has done is to show us that there still persists a hardcore white supremacy racist ideology, which rejects outsiders, anyone who is not white. That ideology is now ascendant as a result of the leadership in the White House. What I see is two great traditions in America that are competing. There is the liberal tradition, and there’s the equally dominant tradition of white supremacy, which comes out of the South but traveled northward. There is real tension between them.

I’ve argued in my writings that there has been extraordinary progress in the changing attitudes of white Americans toward Blacks and other minorities. As late as the early ’60s, a majority of whites openly said they saw Blacks as inferior, and now there is an acceptance of equality, at least in their views. I’ve always said that this may be the great majority, but there’s still 20, 25 percent of whites who still embrace white supremacist views. This hard core of white supremacists is still there and have been encouraged and are leading a revanchist sort of movement. And that’s quite frightening.

Protesters in front of a mural of George Floyd at the scene where he was pinned down by a police officer kneeling on his neck in Minneapolis.

Stringer/Sputnik via AP

GAZETTE: To those who are not white supremacists but may be just be awakening to racial disparities in the nation, what would you like them to know about issues of race in the United States?

PATTERSON: I don’t want to use the term “white people” in general terms because as I said before, what is special about these recent protests is the participation of whites in it, many of them young. But I also see middle-aged and some people my age. I want to emphasize that I think white Americans have gone through quite radical changes in their attitudes, and that we’re talking about a more likely 25 percent of Americans who are hardcore racist, but I think most Americans have quite decent views about race.

But sociologists have argued that while some whites may have liberal views, a lot of them are not prepared to make the concessions that are important for the improvement of Black lives. For example, one of the reasons why people have been crowded in ghettos is the fact that housing is so expensive in the suburbs, and one reason for that is that bylaws restrict the building of multi-occupancy housing. These bylaws have been very effective in keeping out moderate-income housing from the suburbs, and that has kept out working people, among whom Blacks are disproportionate, from moving there and having access to good schools. Sociologists have claimed that while we do have genuine improvement in racial attitudes, what we don’t have is the willingness for white liberals to put their money where their mouth is.

One of the fundamental aspects of the American race problem is segregation. The Black population is almost as segregated now as it was in the ’60s. That is the foundation of a lot of problems that Blacks face, but it also explains and perpetuates the isolation of whites who grow up in neighborhoods where they don’t see Blacks or interact with them. That reinforces the idea that Blacks are outsiders and don’t belong.

GAZETTE: What don’t many white people understand about the life and experiences of people of color in this country?

PATTERSON: Some do; some don’t. I see definitely a change in the younger generation. It’s not just a matter of attitudes. In many ways, young white people are probably the least racist among whites. They are more racially tolerant.

I’ve seen encouraging signs of this. I used to live on Trowbridge Street in Cambridge, and I enjoyed walking through the Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. I was always struck by the easy interaction between white kids and Black kids, which was very different from the 1960s or the 1970s. It shows you what’s possible with a more integrated setting. Now you do have that in many areas, but not enough. In most cases, what you have is largely segregated schools. It’s obvious that if you don’t grow up with Black or white people, you don’t know how to interact with them or how to establish friendships with them. A lot of Black people complain about the awkwardness of interacting with whites who grew up with little contact with Blacks. That’s why I strongly emphasize the need to get rid of ghettos and segregation. It’s beneficial for everybody to have a diverse community in which people are still engaged primarily with their own community, but at least they interact with others.

GAZETTE: How can the country move forward in overcoming the racial divide?

PATTERSON: The immediate issue we’re dealing with right now is police brutality. There will have to be profound rethinking about the organization of police departments around the country. It’s not just a matter of appointing Black police chiefs, because there’s no evidence that that makes a damn difference. Because usually what happens is that they bend over backwards to prove to the majority of the white policemen that they’re being good cops, and the last thing they want is to open themselves up to the charge of reverse racism. What’s needed is a complete rethinking of police culture and the tendency to see the communities they are serving as the enemy. That’s the most immediate thing because police brutality is becoming epidemic. If something isn’t done, as soon as the demonstrations are over, they will quietly go back to doing what they always do.

We also need to address the incarceration rates. I strongly supported [President Barack] Obama, but I don’t think he did enough on that issue. We need to continue reducing the size of the prison population. And we need to take a radical attitude towards de-ghettoization. I prefer to say de-ghettoization rather than integration because we have to get people out of the ghettos, or the inner cities — because not only do the ghettos segregate Blacks from the social and cultural capital of middle-class America, they also make residents easy targets for the police who see the ghettos as the enemy. De-ghettoization is different from integration, although I am in favor of integration, but it does mean Blacks need to get out from these concentrated areas of poverty and move into the broader community.

And lastly, there needs to be a reckoning with the nation’s legacy of slavery and white supremacy, which is grounded in slavery. I spent my whole life studying slavery.

I don’t think slavery was strictly abolished in 1865. What was abolished in 1865 was the personal individual enslavement of one person by another, but what persisted was the culture of slavery, and central to this culture was the sense that the white population felt it was their duty to control and suppress Black freedom. They did this in various ways, through the lynch mob, but also by the use of incarceration, during the neo-slavery system of Jim Crow.

During Jim Crow, what persisted was the attitude to see Blacks as outsiders, as people to be punished, to be held in control, to be denied basic privileges of citizenship or ownership of land and to be recklessly imprisoned. In that sense, slavery was not really abolished in America until the 1960s, when the Jim Crow system was finally and fundamentally dismantled. So of course we need a lot of education in our schools about that and what the consequences were for Blacks, as well as for whites. It’s important that people learn that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.