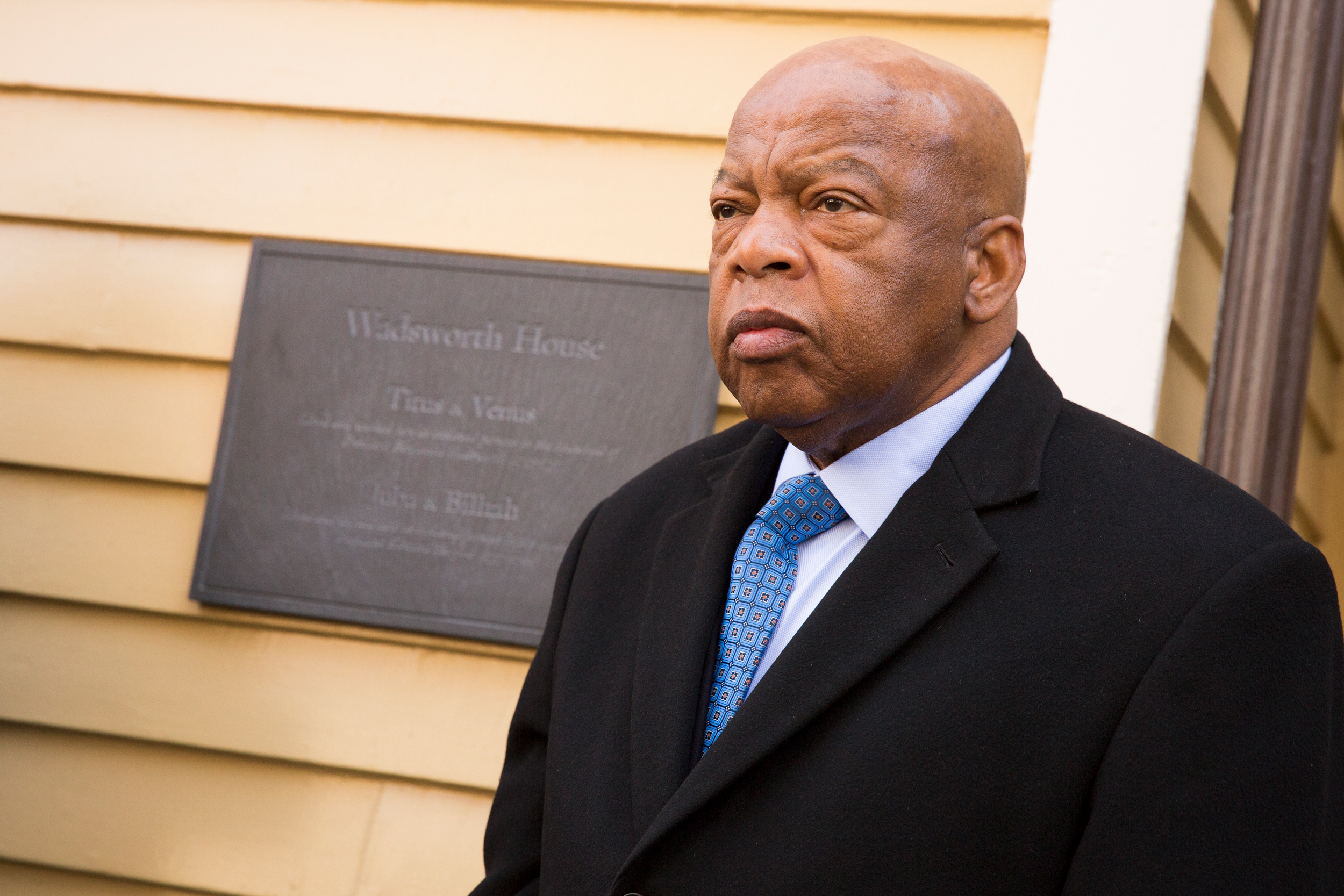

U.S. Rep. John Lewis at Harvard’s 2018 Commencement, where he was principal speaker.

File photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff

The conscience of a nation

Remembering John Lewis, Civil Rights icon and teller of truths

Few political leaders who successfully transition from activists to lawmakers do so without losing the fire and focus on the causes that brought them to prominence. But Civil Rights icon and U.S. Rep. John Lewis, the 17-term Georgia Democrat, was that kind of rare leader, never wavering from his original mission, to see that Black people in America were treated justly, equally, and with dignity.

Unlike other icons of the Civil Rights era whose deaths years ago compressed their memories into historical abstractions for later generations, Lewis was a living, breathing, outspoken testament to the nation’s enduring mistreatment of African Americans. From the Freedom Rides he took to desegregate buses, to the body blows he endured at Selma, Ala., and elsewhere, to the stirring words he summoned to push for bold change, to bearing witness at moments of national triumph and setback, Lewis came to embody the nation’s physical, political. and spiritual struggle over Civil Rights.

Lewis, who was Harvard’s Commencement speaker in 2018 and received an honorary degree in 2012, died Friday at age 80. He had announced in December that he had stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

“The nation has lost a great leader, and Harvard has lost a great friend,” President Larry Bacow said in a statement Saturday. “Throughout his life, John Lewis challenged us to be our best selves, to recognize the decency and value of every human being. His life reminds us of the power of one human being to change the world. He leaves this nation a better, more just place, but one where there is much work yet to be done. We honor his memory by committing ourselves to his relentless pursuit of justice, fairness, and opportunity for all.”

Widely known as the “conscience of the Congress,” he was first elected to the U.S. House in 1986, representing Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, a Black majority area that encompasses most of downtown Atlanta.

Lewis was the youngest, last surviving member of the “big six,” a group of prominent leaders of the Civil Rights era that included James Farmer, Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, and A. Philip Randolph. To illustrate how much Lewis bridged the era, Randolph was born in 1889 and had unionized Black railroad porters in 1925, offering them and their children a pathway from poverty to the middle class.

The son of an Alabama sharecropper, Lewis was a theological student in Nashville when he joined 12 other activists to battle desegregation in the South, embarking on the Freedom Rides in 1961. A fiery and inspirational speaker, he co-founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and led the sit-ins at “whites-only” lunch counters across the South in 1963. He was arrested dozens of times. He also helped organize the landmark March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 and was the event’s final speaker.

In 1965, he co-led the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, where he and hundreds of peaceful demonstrators were attacked by white state troopers with such relentless brutality that the incident shocked public sentiment. Lewis sustained a fractured skull that nearly ended his life. It was a turning point in Civil Rights history, a watershed known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Beyond Civil Rights, Lewis also believed in the transformative power of learning, and he sought to expand access to higher education for African Americans and other historically underrepresented groups. His last public statement as a congressman was a July 10 letter to Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rebuking a plan to block international students from attending college in this country unless some classes were held in-person. Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology sued to block the new policy, and the Trump administration abruptly withdrew it July 14.

Lewis, in addition to receiving an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in 2012, visited Harvard often in recent years. As the University’s Commencement speaker in 2018, he spoke memorably about the importance of righteous resistance or what he often referred to as getting into “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

“My philosophy is very simple,” Lewis told graduates and others in the audience. “When you see something that’s not right, not fair, not just, stand up, say something, and speak out.”

Lewis joined then-President Drew Faust in 2016 for a moving ceremony to formally acknowledge the University’s own complicated history with slavery, unveiling a plaque that named and honored four African Americans who had lived and worked at Wadsworth House in the 1700s when they were owned by Harvard presidents Benjamin Wadsworth and Edward Holyoke.

The Center for Public Leadership at Harvard Kennedy School honored Lewis in 2017 for his 60-year career advancing human rights.

As Americans in 2020, in the age of Black Lives Matter, are demonstrating a new willingness to confront the nation’s history of anti-Black racism, the evocative words spoken by the young Lewis at the March on Washington still resonate: “Our minds, souls, and hearts cannot rest until freedom and justice exist for all the people.”

* * *

The Gazette interviewed Lewis in 2017 about his life’s work, his feelings seeing Civil Rights gains being undermined, and what gave him hope.

Q&A

John Lewis

GAZETTE: The country feels more divided today than in some time. Where is America right now, and where are we going?

LEWIS: I think we are at a turning point. I have been involved for 60 years, really. I have seen and witnessed unbelievable changes. I tell young people, especially young children, when someone says to me “nothing has changed,” I feel like saying “come and walk in my shoes. I will show you change.”

I think we’re in one of the most difficult periods in our recent history as a nation and as a people. There is this sense that that’s all we’re going to do, and there’s not anything else or a role for the national government to play in helping to make real the hopes and dreams and aspirations of people. But to fulfill the dreams of so many — Blacks, whites, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Latinos — we must not let those dreams and the hopes of so many be abandoned or die. In spite of all of the progress that was made — and we’ve made progress, we’ve come a distance — we still have a distance to go.

It is my belief that the scars and stains of racism are still deeply embedded in American society and that people today at the highest level of government want to fan those flames. Some people may not be conscious they’re doing it, but in strange ways they’re still doing it. The Civil Rights Act of ’64, the Voting Rights Act of ’65 have been undermined in so many different ways. The Supreme Court, a few short years ago, put a dagger in the very heart of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

There are people who want to circumvent the lesson, the effect of these two major pieces of legislation. I think there’s still a need for people in high places, not just in government, but in the private sector, in the academic community, in the media, in business to continue to be advocates, bringing people together, and build what Martin Luther King Jr. called “the beloved community.”

“The young kids, they’re just very, very smart. And they will be the leaders of the 21st century. They will take us there. So I’m not afraid.”

GAZETTE: At Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ confirmation hearing, you said, “There are forces that want to take us back. We don’t want to go back.” Is it dispiriting that so many of the issues you fought for 50 years ago appear to be targeted for unraveling by some?

LEWIS: Yes, you look at the appointment of the people to this administration. So many of these individuals are just out of step and out of tune with going forward, with opening up the political process or opening up America and letting people come in. In my estimation, there’s a mean spirit moving around and through our country, and we cannot let that happen without standing up, speaking up, speaking out, and resisting.

GAZETTE: What would it take to get this country to the place the Constitution envisioned, a place where all people are truly created and treated as equal?

LEWIS: I think we’ve got to continue to teach and preach. We’ve got to continue to inspire people to say, “We can do it.” The election of President Barack Obama gave people so much hope. And we cannot let that sense of hope die, and we cannot let it be beaten down, or let it wither on this unbelievable American vine. I tell young children — and adults — that we must not get lost in a sea of despair. We have to be hopeful and be optimistic. Be bold, be brave, be courageous, and just get up and push and pull.

GAZETTE: Where do you see hope today?

LEWIS: I see it among our young people, among our children. They are so smart. The young kids, they’re just very, very smart. And they will be the leaders of the 21st century. They will take us there. So I’m not afraid. It may take a little longer for us to get there because of the recent setbacks. When I move and travel around America, I hear so many people, especially middle-aged and older people, saying, “Congressman, I feel so down; I feel so lost. Do you have a word?” Some people say, “I need a hug.” I say, “I need a hug too.” I have colleagues come to me and say, “What is the word for the day?” And I will say, “Be hopeful, be brave, love, peace.”

“In spite of all of the progress that was made — and we’ve made progress, we’ve come a distance — we still have a distance to go.”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff

GAZETTE: You fought the system from the outside and then the inside. Has it been worth it, and where do you feel you’ve been most effective?

LEWIS: During the late ’50s and especially during the decade of the ’60s was one of my most effective periods because, growing up, I saw and tasted the bitter fruits of racism. I felt the blows of hate. It was easy, it was simple, to help organize a sit-in at a lunch counter in a restaurant or to lead a march or to get out and conduct voter registration drives. It’s unfortunate, but even still today, we have to use some of those tactics and techniques to dramatize the issue, to make it plain, to make it real so people can see it and feel it.

When I was a student in Nashville, Tennessee, during the ’60s and we were planning the sit-ins or going on the Freedom Rides, some of my colleagues said “John, what should we do?” We need to find a way to dramatize it, to make it real, make it plain. And when I moved to Atlanta in 1963 at the age of 23, and I became a member of Dr. King’s father’s church — we called him “Daddy King” — and young Martin Luther King Jr. would be preaching and Daddy King would say, “Son, make it plain; make it real.” I really believe that the Women’s March the day after the inauguration sent a powerful message around America and around the world. People understand now, and perhaps more than ever before, the power of voting with their feet, not just casting a ballot on Election Day.

GAZETTE: When you look back, do you feel like you achieved what you set out to accomplish? If not, what else is left to do, and how can that happen?

LEWIS: What I think is important is that we have not yet created the “beloved community.” We’re not there; we still have a distance to go. The signs that I saw growing up, the signs that I saw in Nashville, in Atlanta, and all across the South during the ’50s and ’60s that said “white men/colored men, white women/colored women, white boys/colored boys,” those signs are gone. And the only place those signs today would appear and we would see them would be in a book, in a museum, or in a video.

But we have these invisible signs that discriminate or put people down. I think it’s a shame and a disgrace today that in America we have hundreds and thousands and millions of people, and especially young children, living in fear. They’re afraid to go to school, they’re afraid to leave their homes, they’re afraid that their mothers or their fathers or their grandparents will be taken from them and they will be sent to some prison or jail or put on a bus, a plane, and be taken back to some other part of the world. When Pope Francis came and spoke to a joint session of Congress, he said we’re all immigrants; we all come from some other place. We need to deal with the whole question of immigration reform and set people on a path to citizenship.

GAZETTE: What do you say to young people who want to work for change but aren’t sure what they can do or where they can be most effective?

LEWIS: I say to young people all the time, whether in high school or college or young people out in the work force or working on Capitol Hill, I say when you see something that’s not right, not fair, not just, you cannot afford to be silent. You have to do something. Wherever you find yourself, speak up, speak out, and find a way to get in the way, to get in what I call “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

When I was growing up, and asked my mother and my father, my grandparents, and my great-grandparents about the signs and about segregation, they would always say, “Don’t get in trouble; don’t get in the way.” But I met Rosa Parks when I was 17, and the next year, at the age of 18, I met Dr. King. And those two individuals inspired me to get into what I call “good trouble.” And I’ve been getting into trouble ever since.