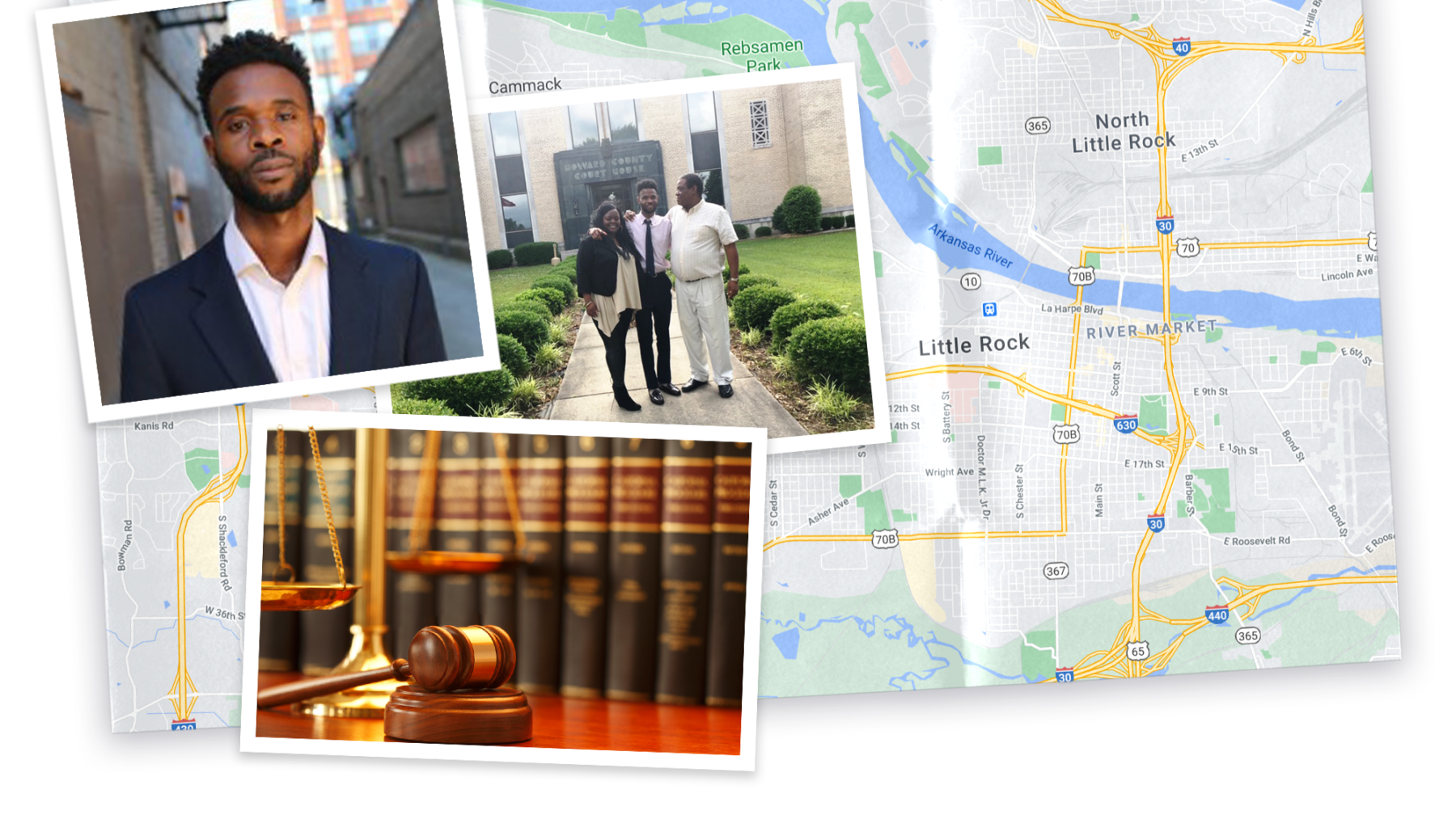

Omavi Shukur went into law because he felt it was “the most effective route to go on that [would] allow me to help change people’s material reality for the better.” Above, Shukur stands with client Joseph Sauls Jr. and his daughter in rural Arkansas after a criminal jury trial victory in 2017.

Photos courtesy of Rachel Smith, Tony Walker, and from iStock.

Undoing injustice

“People have to know about the injustices that are occurring in their name.”

Omavi Shukur, J.D. ’12 left Little Rock, Ark., in 2005, for New York City and Columbia University seeking an answer to a question: Why do people in many Black communities like his have to fight “to the point of exhaustion” simply to get a fair shot at life?

“Kids that were just as bright as me had to face obstacles that I didn’t have to face, and it was not of their own making. And … I loved my peers,” says Shukur.

During his undergraduate years, Shukur began to form an explanation: The fact that certain communities experienced disproportionate economic inequality, lack of opportunity, incarceration, and unhealthy living environments wasn’t due to random instances of misfortune or cracks in the system — it was by design. A feature, not a bug. And so a question became a mission.

“Nuts and bolts policies help structure our reality and communities such as Little Rock, and [other] marginalized communities,” he says, referring to statutes like zoning laws used to exclude and segregate Black communities. “Coming up you’d [think] that’s just the way it is. That’s just happenstance,” he says. “[L]earning about how policy informed our reality, I got a new appreciation for [how] the toxic environment in which we came up in was actually manufactured. … Within a half mile radius of my high school, to this day, are drive-through liquor stores and tobacco shops, and fast food restaurants.”

After college, Shukur decided that the best way he could help bring about broader, systemic changes was to become a lawyer. During his first year at Harvard Law School, Shukur saw social justice activist and law professor Bryan Stevenson speak, which inspired him to spend a summer working at Equal Justice Initiative, the nonprofit Stevenson founded in Alabama. After graduation, Shukur moved to New Orleans to work in the public defender’s office before deciding in 2015 it was time to head home.

“I … felt that I had a debt that I owed to the community, and Little Rock, that had invested in me,” Shukur says, referring to literacy and arts magnet programs he attended in public schools (which were under an active desegregation order at the time). “I wanted to give them a return on their investment.”

Back in Arkansas, Shukur founded Seeds of Liberation, an education and advocacy organization focused on supporting and empowering formerly incarcerated people and those impacted by incarceration.

“At this time Arkansas was the fastest growing prison state in the nation,” Shukur says.

“My pie in the sky would be to have a new means of addressing behavior that has been labeled criminal that is primarily … informed by people directly impacted by incarceration, but also primarily administered or instructed by behavioral health specialists.” Shukur at a Little Rock rally against police violence in June 2020.

Photo courtesy of Holly Dickinson

In addition to providing resources to formerly incarcerated people, Shukur dedicated himself to talking to anyone who would listen — institutions, elected officials — about the incarceration crisis. He also published a paper in the Arkansas Journal of Social Change and Public Service about the topic. Often when giving speeches, Shukur says that he “was shocked by just the complete silence. … People have to know about the injustices that are occurring in their name.”

Shukur also helped establish a support group for those affected by incarceration. At one point, Shukur asked the group what types of policy changes they hoped for. “Much to my surprise, they didn’t mention more robust Fourth Amendment protections [against unreasonable searches or seizures] or housing subsidies or anything like that. They just said, … ‘We want to eat.’” In many states, including Arkansas at the time, people with felony drug convictions were not eligible for food stamps, job training, or temporary financial assistance for families. “It’s like a recipe for disaster,” Shukur says.

In response to this, then-state Representative John Walker, working with Shukur and other community leaders, introduced legislation to bring an end to the ban on food stamps and welfare benefits for people with felony drug convictions. “This is 2017. So this is Trump’s America, in Arkansas, and not a single legislator voted against the bill. It sailed through and passed … it was just amazing,” recalls Shukur of what he describes as the high point of Seeds of Liberation.

Now a staff attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Shukur lives in New York, but he’s still litigating cases in Arkansas, including a lawsuit over the recent police killing of a Black man named Bradley Blackshire.

“It’s becoming, with every day, clear that we don’t have the luxury of being able to ignore the structural deficiencies that result in all the tumult that we see in our society,” Shukur says. “The various inequities that exist, they’re not sustainable. …The question for me is not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when and how … I can be of service.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.