John Moeses Bauan/Unsplash

How old are you for your age?

Scientists who study aging have begun to distinguish chronological age: how long it’s been since a person was born, and so-called biological age: how much a body is “aged” and how close it is to the end of life.

These researchers are uncovering ways to measure biological age, from grip strength to the lengths of protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, known as telomeres. Their goal: to construct a comprehensive set of metrics that predicts an individual’s life span and health span — the number of healthy years they have left — and illuminates the drivers of, and treatments for, age-related diseases.

A team led by David Sinclair, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, has just taken another step toward this goal by developing two artificial intelligence-based clocks that use established measures of frailty to gauge both chronological and biological age in mice.

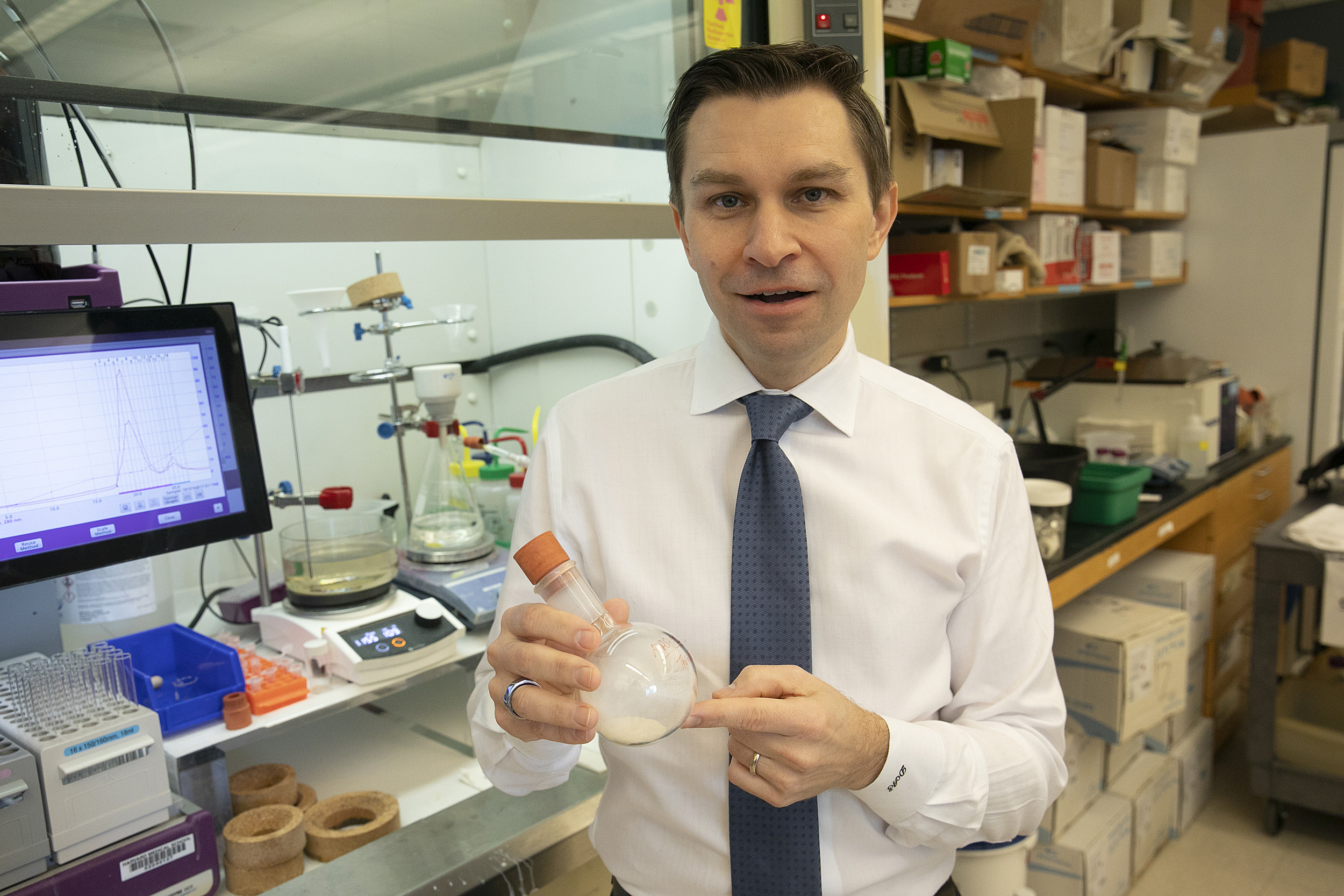

David Sinclair displays an evaporator device used in the lab for aging research and drug discovery.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“We are working to predict mouse health spans so we can quickly assess the effectiveness of interventions intended to extend life and move toward doing the same one day in humans,” said Sinclair, senior author of the study, published Sept. 15 in Nature Communications.

The work marks the first time a study has tracked frailty for the duration of a mouse’s life, the authors said.

“It can take up to three years to complete a longevity study in mice to see if a particular drug or diet slows the aging process,” said co-first author Alice Kane, Harvard Medical School (HMS) research fellow in genetics in the Sinclair lab. “Predictive biometrics can accelerate such research by indicating whether an intervention is likely to work.”

The findings

The team tracked the health of 60 aging mice for more than a year, until they died naturally. Health was measured by a standard set of noninvasive tests that provides a frailty score. Such tests were first created for people before being adapted for mice. Examples include walking ability, back curvature, and hearing and vision loss.

The researchers then trained two computer models to learn from the mouse data. The Frailty Inferred Geriatric Health Timeline, or FRIGHT, clock gauges how biologically old a mouse is based on its frailty status. The Analysis of Frailty and Death, or AFRAID, clock predicts how much longer an old mouse has to live, up to one year ahead of time. Predictions in the study were accurate to within two months.

The researchers went on to track frailty in two groups of mice given treatments or diets shown to extend life or health span in previous mouse studies. The clocks accurately predicted whether each intervention would improve biological age or lead to longer life.

“[Multiple] diseases … predominantly affect older people. We want to understand how the aging process itself works so we can find ways to reduce the incidence of all these diseases together, rather than one at a time.”

Alice Kane

The lab has made the clocks freely available for other researchers.

The researchers also found that some measures of frailty correspond better to age and longevity than others. For instance, hearing loss and tremor were more strongly linked than vision and whisker loss. The authors propose giving certain factors more weight when calculating biological age.

The team chose the model names because aging and death are frightening to many people.

“Many aspects of aging are indeed scary, and we want to find ways to prevent or reverse them so we can all stay biologically younger for longer,” said co-first author Michael Schultz, a Harvard Medical School research fellow in genetics in the Sinclair lab. “A recently developed clock from UCLA based on DNA methylation patterns in humans is called GrimAge, so the names for our clocks certainly fit within the same theme,” he added.

The limitations

The clocks were assessed only in male mice. The lab is now expanding its studies to female mice.

Mice are not people; the clocks cannot yet be used to predict human health, biological age or longevity. The researchers caution that humans have far more complex biological, physiological, behavioral, environmental and social influences on health and disease.

Since frailty indices already exist for people, in principle “it would be relatively straightforward” to develop a life expectancy clock like AFRAID for humans — “if we had the proper data set,” said Schultz. “However, such a large, longitudinal dataset that tracks people from their 60s into their 90s with significant mortality follow-up data is not available, to our knowledge.”

The models would also be strengthened by incorporating molecular markers alongside the current physiological ones, the authors said.

“Finding a less expensive or less invasive way to test the molecular underpinnings of physiological signs like gait would help us make earlier and more accurate health span predictions and interventions,” said Schultz.

[gz_explore id=”223408,292034,267475″ alignment=”right” /]

The team and others continue to work toward that ultimate goal.

“Diseases like cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, neurodegeneration and even severe COVID-19 predominantly affect older people,” said Kane. “We want to understand how the aging process itself works so we can find ways to reduce the incidence of all these diseases together, rather than one at a time.”

This work was supported by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, National Institutes of Health (R37AG028730, R01AG019719, R01DK100263, R01DK090629-08, 5T32GM070449 and 2R56AG036712-06A1), an Epigenetics Seed Grant from the HMS Department of Genetics (601139_2018), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PGT 162462) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (G-19-0026260).

The authors declare they are not filing patents or forming companies based on this study.

Sinclair’s financial disclosures can be found here. Co-author Michael Bonkowski is a stockholder of MetroBiotech and Animal Biosciences, a division of Life Biosciences. Other authors have no conflicts to declare.