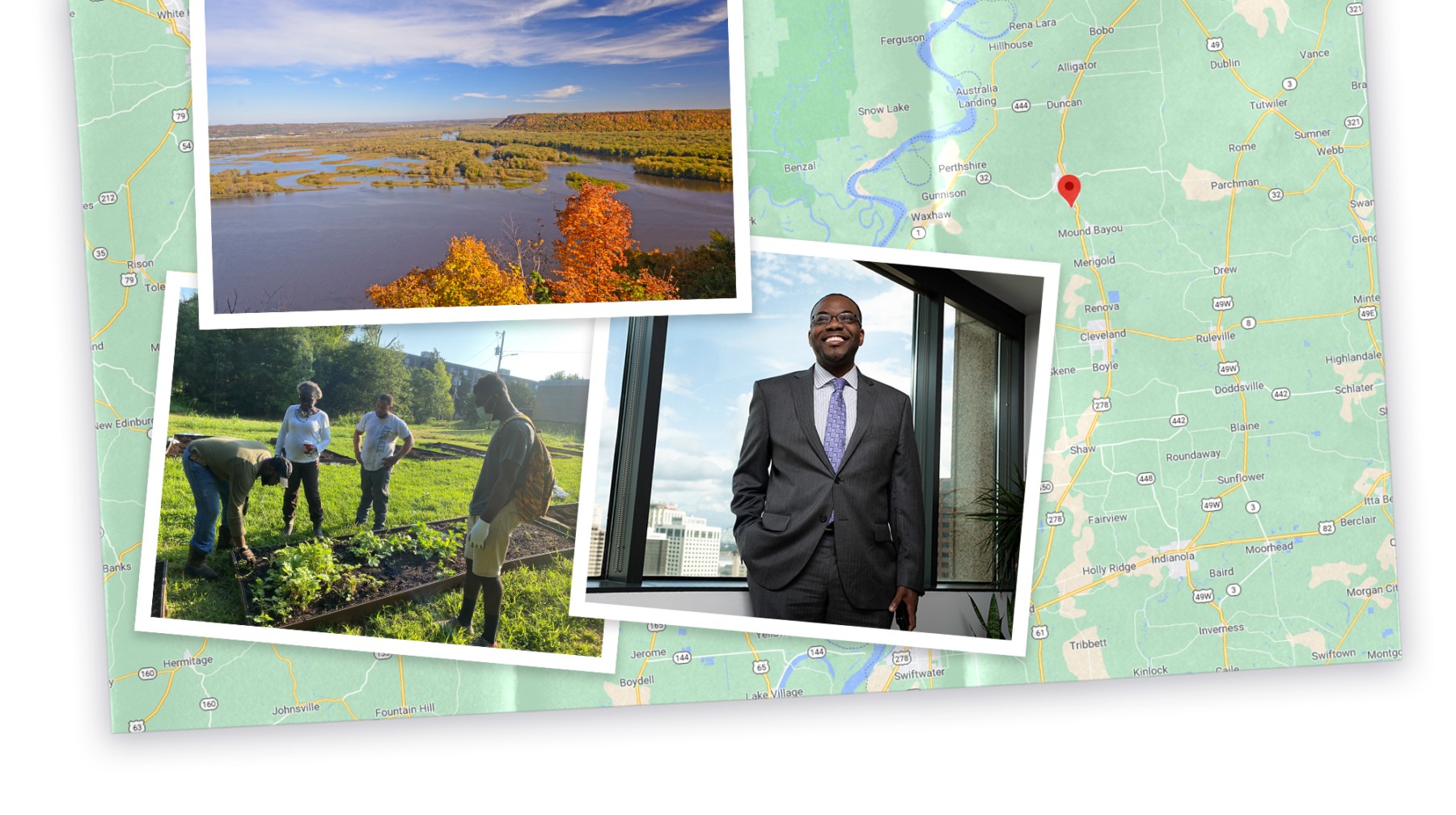

Julian D. Miller has created a center for justice in his home state of Mississippi that aims to foster lasting change.

Photos courtesy of Julian Miller, Forman Watkins & Krutz LLP, and from iStock

Fertile ground

“It’s not truly success if it doesn’t have this greater sociable benefit for those around you.”

When Mississippi Delta native Julian D. Miller, A.B. ’07, got to Harvard College he was overwhelmed with the possible paths his life could take. “I think I wanted to be a screenwriter,” he remembered contemplating at one point, before following his lifelong interest in politics, with a plan of working in Washington, D.C.

Two years into his government concentration though, his grandmother needed help recovering from surgery, so Miller took the year off from school. Back home in Winstonville, Mississippi, in addition to his role as a caregiver, Miller got some first hand experience with local politics, serving as a policy director for the congressional campaign of local politician Chuck Espy and helping coordinate direct support to Katrina victims through the Community Relief Foundation.

After his grandmother recovered, Miller returned to Harvard and finished his last two years with a clear path in life: coming back to Mississippi and helping those who are struggling.

“The issue to me seemed that there had to be a meeting of the grassroots and the top level. These institutional resources,” such as federal grants, “need to be brought down to the grassroots level. A connection needed to be made,” he said.

Miller decided that enrolling in law school would give him better access to and understanding of that top level, but before that he wanted to get more direct, hands-on experience with anti-poverty initiatives.

“I was able to reconnect with my first grade teacher, Sister Theresa,” who was working with a group of middle school and high school girls looking to do community service in the Mississippi Delta town of Jonestown.

“They came up with this idea called Clutter 2 Compost, where they would collect all this yard debris,” which a recent law made it illegal to burn, “break it down and make it into compost, and sell the bags of compost in the same program.”

“That was the first grant I had ever written and received,” Miller said, adding that the economic sustainability of that program — selling the bags at a price that supported further growth — really opened up his eyes to how change can last.

“If we can develop a sustainable economy in the Delta that’s worker owned, we can essentially create revenue to address social problems.” Which is exactly what Miller did with his next project.

Just before entering the University of Mississippi School of Law he co-founded the Delta Fresh Foods Initiative, a community of growers, health and agriculture educators, schools, and food retailers committed to creating equitable community food systems in the region.

In addition to co-founding the Reuben V. Anderson Center for Justice, Miller also co-founded the Delta Fresh Foods Initiative and directs the Reuben V. Anderson Pre-Law Program at Tougaloo College.

Photos courtesy of Julian D. Miller

“The Delta has some of the most fertile soil in the world,” Miller explained, but added that most of the farming in the state isn’t owned by local growers. This initiative is working to change that, one county at a time.

After law school, Miller realized that he now had the education and experience needed to create change; the next step was gathering a coalition of people under one roof to make it work on a large scale.

“The idea was that the Reuben V. Anderson Center for Justice would be responsible for doing grassroots community development and policy work around economic justice, educational equity, criminal justice equity, and public health equity,” Miller explained.

The center, which Miller co-founded with fellow Mississippi lawyer Raina Anderson, is named after and created with the support of Raina’s father, the civil rights lawyer who became the first African American justice of the state Supreme Court in Mississippi. The nonprofit, which officially launches next year, has already started addressing the needs of the community.

“We’ve already established projects on the economic justice front,” Miller said about a multiphase community food system they implemented at Tougaloo College, where the center is based.

He added that they’ve also partnered with Mississippi College School of Law to create a law clinic focused on providing pro bono representation in school disciplinary matters as well as impact litigation and policy advocacy around issues of educational equity, a student mentorship program that teaches children math, science, and writing through community garden projects, and that the center is working on a job placement and academic enrichment program for formerly incarcerated individuals.

Because of his intentional approach and his focus on self-sustaining programs, Miller is confident in the long-term success of the center.

“We’re a model of how a poor southern state that had been racially divided, that had been economically exploited … can build collective action, and collective organizing around these anti-poverty issues and actually [move] the state forward and demand policies that respect the dignity of every human being.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.