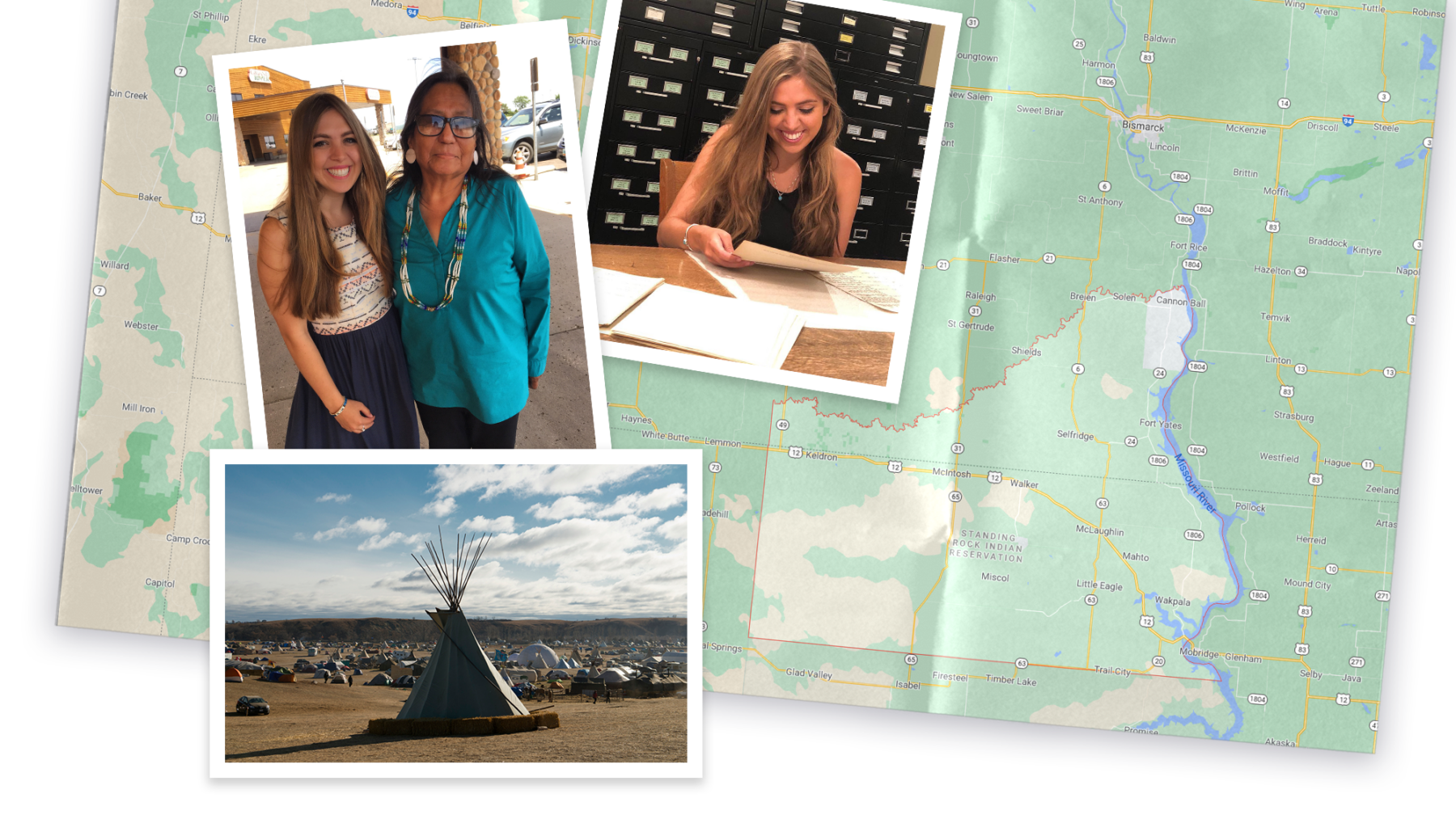

Photos courtesy of Sarah Sadlier and from iStock

Bringing law to life

“Anytime that you can raise awareness, or address the invisibility of Native American issues in the academy is incredibly impactful.”

For Sarah Sadlier, joint Ph.D and J.D. candidate, studying history isn’t merely about understanding the past but about the insight it lends the present and guidance it provides for the future — especially when it comes to law.

“[There’s an] incredible amount of connection between the law and history,” says Sadlier, who is currently pursuing joint Ph.D. and J.D. degrees with a focus on Native American history and American Indian law at Harvard. “Historical research is often a great asset when doing legal research.”

Sadlier has done a lot of this recently, including using it to build legal cases and testimonies, updating legal guidebooks, and working on presidential candidate Joe Biden’s Native American Policy Committee to come up with legislative solutions and protect treaty rights.

Sadlier’s interest in Native American history and law isn’t purely academic. It’s also deeply personal.

“I’ve always been interested in history and the law, largely because of my family history and involvement within it,” says Sadlier. “My family is Lakota. My grandfather moved from South Dakota to the Tacoma, [Wash.,] area. And he was one of the first Native American lawyers. [H]e worked on the Fish Wars cases with the Puyallup [people],” the successful ’60s and ’70s litigation and civil disobedience that challenged the State of Washington’s attempt to restrict tribal fishing rights in violation of treaties from over a century before.

A key to protecting old treaties is educating law school students about them in the first place. American Indian law is often completely absent from law school curricula. Sadlier hopes to change this, in part through teaching.

But educating is not all she plans to do, which is why she decided to also pursue a law degree in addition to a Ph.D. The move was inspired by a summer that Sadlier, who is from Washington State, spent in Bismarck, N.D., working with the Lakota People’s Law Project (LPLP), an advocacy group that works to secure the Lakota people’s rights to autonomy and self-determination, reclaim Indigenous land, and revitalize their culture.

“I had never thought about attending law school because I’d always wanted to be a professor,” Sadlier recalls. “The moment that changed my mind was when I was in the Dakotas working with Lakota People’s Law Project and organizers on the ground and realizing how fulfilling it was to be able to participate in this movement in a meaningful way.”

Sadlier spent her summer 2020 legal clerkship working to update the Native American Rights Fund’s Guidebook, the legal guide to the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 which ensures that states do not remove children from their families or Indigenous communities, and promotes tribal sovereignty.

Photo courtesy of Sarah Sadlier

North Dakota is the homelands of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations, the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, the Spirit Lake Tribe, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, and other Native nations. While there, Sadlier contributed legal research related to the No DAPL Movement at Standing Rock, which sought to shut down construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline that would run near the Standing Rock Reservation and threaten important cultural sites and the safety of the region’s water supplies.

“I basically worked on establishing the historical narrative of what had happened at Standing Rock so [it] could be presented to the judge in a condensed but understandable, concise history,” Sadlier says, referring to the protests of the pipeline and the arrests of protestors, including water protector and LPLP lead counsel Chase Iron Eyes, who was charged with inciting a riot. “I got to interview and work with tribal members at Standing Rock … [it] was incredible to be mentored by people there.” As an expert witness and scholar of history, Sadlier can provide the historical context of a law, treaty, or event to help a judge understand all the factors that are at play.

Since her time with the LPLP, Sadlier has conducted historical and scholarly research for other legal projects. Recently, she updated the Indian Child Welfare Act Handbook, the legal guide to the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, enacted to ensure that Native American and Native Alaskan children who were up for adoption would be placed in Native American homes. This was especially personal for Sadlier, whose own family from the Dakotas were sent to the Hampton Institute, which some consider to be the first of the “Indian boarding schools”, institutions founded in the late 19th century to strip Native children of their culture and language and forcibly assimilate them.

“The legal issues affecting tribes do span the gamut, from environmental law to criminal law,” Sadlier says. “Native American history is often omitted, both from scholarship, but even statistics.” And, she adds, Native Americans are startlingly underrepresented in the legal field. “Native Americans make up roughly 0.2 percent of lawyers, and around 1.5 percent of the national population. So those statistics are suggesting that there needs to be much more representation of Native people in this field.”

Native Americans need to be included when it comes to decisions that affect their communities, Sadlier says, and historically, they haven’t been. “Any work that you can do to raise awareness can be helpful moving forward in getting people energized,” Sadlier says, “or at least [getting them] to acknowledge … that Native Americans are part of our broader community as well, and should be included in policy conversations.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.