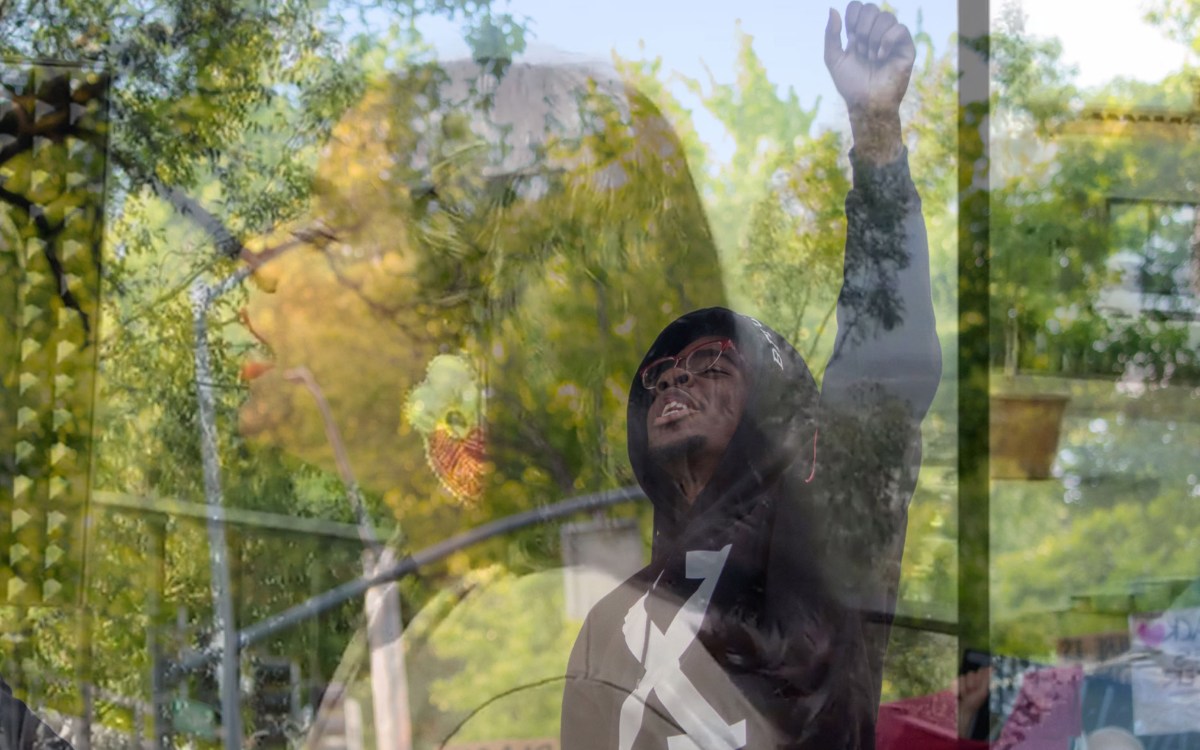

“The ‘Dragon Cycle’ was never meant to be my memoir alone. It was meant to be my family’s memoir, specifically my grandmother’s, my mother’s, and my memoir,” says Sara Porkalob.

Photos by Gretjen Helene Photography ©

‘Dragon Cycle’ examines race, class, gender, and identity

Sara Porkalob’s one-woman show traces lives of Filipina immigrant, her queer daughter, and embattled granddaughter

Seattle-based actor/writer Sara Porkalob makes it clear that she understands difficult choices in the generational triptych that makes up her acclaimed “Dragon Cycle” plays. In “Dragon Lady,” Porkalob explores her grandmother’s desperate decision to flee violence and poverty in the Philippines to come to an America that was openly hostile to immigrant women of color.

“Dragon Mama,” which had its premiere at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) in 2019, recounts the tale of the writer’s queer mother, who left baby Sara behind in Washington state while she herself headed to Alaska for a fishery job and a chance to support her family. “Dragon Baby,” an A.R.T. commission, takes on Porkalob’s own story of facing down sexism and sexual violence, white supremacism, and the grinding poverty of minimum-wage jobs before achieving theatrical acclaim.

Although live theater has been halted by the pandemic, the A.R.T., under the leadership of Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director Diane Paulus and executive producer Diane Borger, is bringing Porkalob’s inspiring work to audiences. As part of its “Virtual Oberon” lineup, “Dragon Mama” will begin streaming Thursday, with a virtual premiere at 7:30 p.m. (The Elliott Norton Award-winning production will be available on demand through Dec. 10.) Porkalob will also kick off the A.R.T.’s “Behind the Scenes” discussion series on Monday. (Information about tickets, including a pay-what-you-can option, may be found at AmericanRepertoryTheater.org.) She recently spoke with the Gazette over Zoom about her work and theater during the pandemic.

Q&A

Sara Porkalob

GAZETTE: These plays recreate the stories of the women in your family, but they are artistic creations. How much is interpretation?

PORKALOB: It’s all 100 percent true. The “Dragon Cycle” was never meant to be my memoir alone. It was meant to be my family’s memoir, specifically my grandmother’s, my mother’s, and my memoir. And that requires me understanding that people can experience the same event in very, very different ways. Some people might call that creative license, but I’m not creating something out of nothing. I’m literally trying on my family’s different perspectives around a series of events.

GAZETTE: Has this process changed how you view your family?

PORKALOB: It’s definitely changed how I see my family, and how my family sees each other too. When I’m seeing these people who made me onstage, I’m seeing that often people are trying to do the best they can with what they have. People can be mean and harmful and racist and sexist and abusive, and there’s always a reason for that. Maybe it’s because they were abused; maybe because they didn’t have anybody to support them and tell them that they were great. Like, my grandmother loved her kids. She was not a good mom. She tried to deal with what she had. My mother loved me. She saw my grandmother was not a good mom. And she decided to make different choices to try to be a better mother to me.

GAZETTE: You chose some really tense moments to highlight. I’m thinking of when people comment on your skin color or your hair, questioning your identity as a person of color.

PORKALOB: I didn’t even really have to choose. They just revealed themselves. It was amazing to me to realize, “Oh, this is something that was said to my grandmother when she was my age,” and that was accompanied by an attempt to rape her. In the 1960s that was said to my mother in a queer bar. But because there were queer folks around, they were able to get that guy out of there. That was said to me on a street corner, and I was able to like clock the guy. History repeats itself, but we have the agency and autonomy to make different decisions.

GAZETTE: You share such intimate and often painful moments with the audience. Do you have an idea of who that audience should be?

PORKALOB: I want an audience that looks like my family, of course. I don’t stand on stage thinking that I’m going to educate white people. I don’t stand on stage thinking that I’m going to be a savior. My responsibility is to tell the truth, to do my job as a storyteller by honoring my family and by telling the truth. Anybody there who’s present to witness it, I am thankful for, until they prove themselves otherwise.

I want to trust my audience — to trust them with the truth. And if they can’t handle it, that’s not my problem. And that frees me. That means I’m not performing exclusively for them — to make them feel. I’m never up there being like, “I’m going to make my audience cry. I’m going to make them laugh.” I’m up there being like, “I’m going to tell the truth.” I think I’m funny. I think I’m good. My family is awesome. Let’s do this.

GAZETTE: Do you miss having a live audience?

PORKALOB: I didn’t miss them for the first four months of the pandemic, because for the first time in eight years I finally had a break. I said, “Yay. I want to do everything that I’ve been putting off. Clean under the bed. Get some plants. Go to Goodwill. Focus on my physical health.” And then about four months in, I was like, “Man, I did everything on my list. I miss performing.”

GAZETTE: You’ve been cast as Edward Rutledge in the A.R.T.’s delayed production of “1776.” How does that feel?

PORKALOB: I’m excited for my [inevitable] Tony nomination!

GAZETTE: You aren’t concerned about the limitations of acting out someone else’s words?

PORKALOB: It could have been in the hands of another theater company, and I would have said, “No, thanks.” But we have Jeffrey Page and Diane Paulus and this incredible team of Harvard scholars and community activists and a cast full of full of trans, non-binary, female-identifying people who want to reclaim the story of our history and to challenge our audience, to reckon with our white supremacy culture.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.