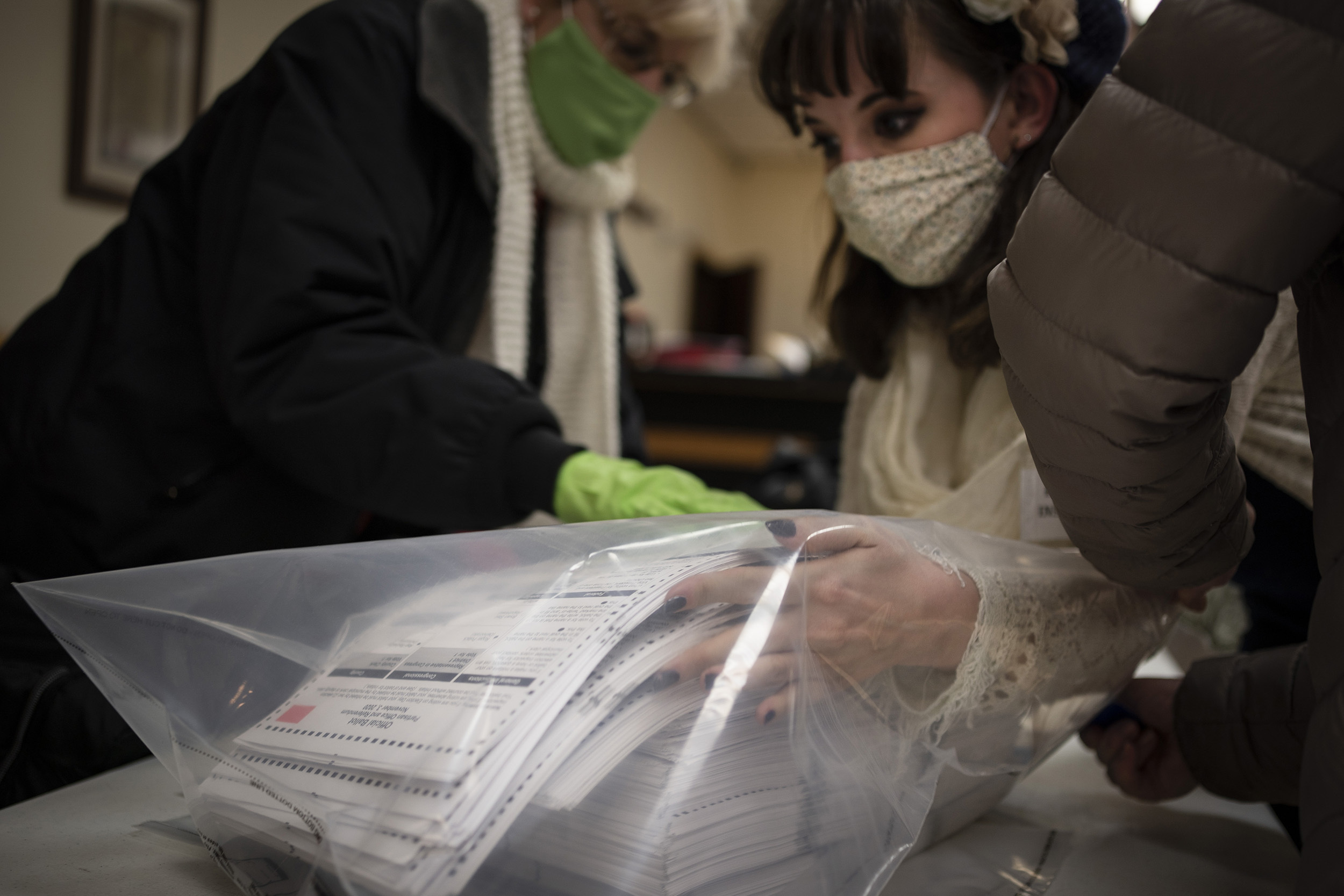

Election staff members pack ballots after polls closed on Election Day at the Moose Lodge in Kenosha, Wis.

AP Photo/Wong Maye-E

Legal experts shake their heads at GOP election suits

Don’t expect them to be successful, but they could prove useful to Trump in other ways

President Trump has made no secret of his intention to file legal challenges in key states where election results were close, citing the possibility of voting fraud. For months, he has criticized the nationwide expansion of mail-in balloting, a longstanding practice that gained ground rapidly because of social-distancing concerns during the pandemic.

Trump filed lawsuits Wednesday to stop vote counts in Pennsylvania and Georgia, along with Michigan, shortly before the Associated Press said his opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden, had won the state. Officials are still counting votes in Nevada, Arizona, and Pennsylvania, which only started tallying more than 3 million mail-in ballots on election night. The Trump campaign complains that some states have failed to give its observers adequate access to view ballot processing and counting. The campaign has not provided evidence of fraudulent mail-in voting. With only a narrow margin separating the two candidates, Trump’s campaign said it will seek a recount in Wisconsin, which news organizations also awarded to Biden Wednesday, edging him closer to the 270 electoral votes needed to win.

But scholars are not convinced there’s a plausible argument that the president’s legal team could make in these new actions that would prove successful in court.

President Trump calling the judges he nominated to the federal bench “his judges” will not work in his favor, says Laurence H. Tribe, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor and Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

“There’s no claim I can think of that would shut down the counting of lawful, valid mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania,” said Harvard Law School Professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos, who studies election law.

Given the electoral vote count Biden has amassed in other states, it’s not a foregone conclusion that the Supreme Court would take the case.

“The court is heavily political and heavily ideological, but they’re smart. I think they’d take the hit if it meant Trump could win the election, but they’re not going to take the hit to their legitimacy by getting involved if it’s just going to get Trump another 1,000 [votes] in some Pennsylvania suburb,” said Stephanopoulos. “Everything depends on whether a lawsuit can be pivotal or not.”

In the run-up to Election Day, the Trump campaign filed numerous lawsuits challenging states and counties that had expanded their methods and timetables for voting to minimize COVID-19 health risks. The campaign lost cases that claimed mail-in ballots should be disallowed because they were susceptible to fraud.

“I think one part of it is as a Hail Mary and the other part of it is to create a basis for claiming the outcome is not politically legitimate.”

Alex Keyssar, Harvard Kennedy School

Though the president nominated hundreds of judges to the federal bench during his tenure, the courts aren’t likely to simply go along with the president’s demands, analysts said.

“I think the very fact that the president has advertised that they are ‘his’ judges that he’s relying on to stop the counting both dares them to assert their independence in a way that is going to make it less likely that they will depart from what is a normal legal way of thinking about this and, ironically, undermines the effort he’s likely to make, [which is] to claim that Biden is somehow an illegitimate president because it will be Trump’s own judges who will be rebuffing his attempts,” said Laurence Tribe, Carl M. Loeb University Professor emeritus at Harvard Law School.

While such lawsuits may not ultimately succeed as a legal tactic, they could be a very effective political tool for Trump.

“I think one part of it is as a Hail Mary and the other part of it is to create a basis for claiming the outcome is not politically legitimate,” said Alex Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School.

“I’m going to be extremely surprised if, when all is said and done, he says, ‘It was a good, close election. It was a tough battle. Biden won; I congratulate him.’ He’s going to say ‘I really won, but it was stolen.’ He’s just setting himself up to give himself ways of saying that,” said Keyssar.

In terms of political exit strategies, there have been other close, contested elections, most recently George W. Bush and Al Gore in 2000 and the 1960 race between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. In both cases, the losing candidate ultimately chose not to dispute the results or accuse the declared winner of cheating.

Trump may adopt a more aggressive strategy that would tend to fit with his persona and align with a campaign that made questioning the election’s eventual legitimacy a core narrative, said Keyssar.

“It’s kind of who he is. It will satisfy his supporters; it will create a basis for him to do stuff next and to wallow in grievance,” he said. Whether it’s effective as a long-term strategy is unclear.

Trump has expertly tapped into the court system for years in his business dealings and political life to delay and derail undesirable and seemingly unavoidable outcomes.

Stephanopoulos is fairly confident that such a legal blitz may, in the end, be rendered moot by the voters.