Voters are more unified than they may seem, says Danielle Allen, director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

What the election may tell us about the future

Five Harvard experts in government, ethics, economics, and sociology weigh in

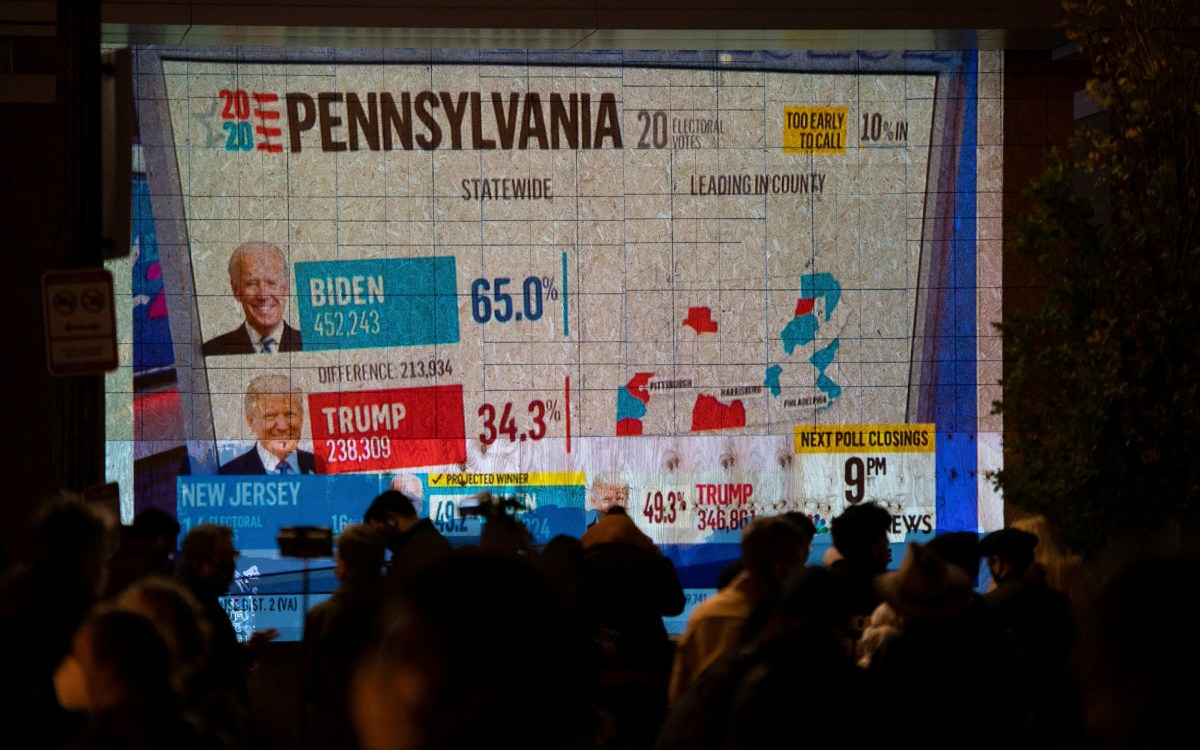

The country may be divided, but this month’s presidential election saw the highest turnout of any in the past century. The five panelists on a Tuesday roundtable, “Implications of the 2020 Election,” had different takes on the results, but they all found a favorable sign in the newly energized electorate.

Co-sponsored by the Harvard Alumni Association and the Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning, the virtual panel brought together six of Harvard’s faculty political experts, including Professor of Government Jeffrey Frieden, who served as moderator.

“We’ve had the whole electorate in the conversation for the first time. That’s historically monumental,” said Danielle Allen, director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, who cited increased turnout by people of color, Native Americans, Asian Americans, young people, and those without college degrees. “From a civic education point of view, that is a transformative moment.”

She said that certain ballot propositions, including the legalization of marijuana in 11 states, indicate that voters are more unified than they may seem and suggested that ranked-choice voting (which failed in Massachusetts) might yield less divisive candidates. “But the irony there is that ranked-choice voting is something on which the American people are themselves divided,” she said.

Stephen Ansolabehere, Frank G. Thompson Professor of Government and Director of the Center for American Political Studies, similarly suggested the idea that Americans had become more polarized since 2016 had been overstated. He shared a county-by-county graph showing that levels of Democratic and Republican support have been “stunningly stable” since the last election — with one notable outlier in Florida’s Dade County swinging Republican. And he speculated that Trump may well have won re-election if it weren’t for the pandemic. “This election was about COVID, and the effect it had on the economy and society. People started to see the administration differently.”

A more lasting change, he said, will likely be the popularity of advance voting. “Twenty-twenty witnessed the end of Election Day. The people who get into the exit polls are the unusual voters, they aren’t representative anymore.”

Professor of Government Ryan Enos argued that “hand-wringing” over the Democrats’ performance in 2020 is unnecessary, given Biden’s vote margin — the highest against an incumbent since 1932 — and the fact that Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the last eight contests. “If you look at American history, that’s a streak of electoral strength that’s unrivaled,” he said.

Still, he noted that major changes emerged in two demographic groups: suburbanites and Latinos. The former shifted significantly Democratic this year, the latter Republican. It’s possible, he said, that both were simply responding to Trump’s personality. But it’s also possible that the two parties are now changing their traditional places, with Republicans becoming the party of the working class and Democrats of the professional class. “If this is the future, we can imagine the suburbanites remaining in the Democratic fold, where their wealth and education makes them part of the coalition.”

The 2020 election was partly a reaction to the previous one, said Roger Porter, IBM Professor of Business and Government. “We essentially replaced someone who had no experience in government with someone who had extensive experience. At the same time, we continued the pattern of divided government that we have now moved into.” Biden’s level of experience, Porter suggested, will likely help in the two biggest challenges he faces, negotiating with the Senate and managing the pandemic.

Ryan Enos (clockwise from upper left), Theda Skocpol, Stephen Ansolabehere, Jeffry Frieden, Danielle Allen, and Roger Porter discuss “Implications of the 2020 Elections.”

Porter worked on five presidential transitions as a White House senior economic adviser, and Frieden asked what sorts of problems might be caused by the current rocky transition. “Life should be filled with graceful entries and exits, and Mr. Trump’s exit is not graceful,” Porter replied. But he said there are laws in place, notably the 1963 Presidential Transition Act, to ensure that things ultimately run smoothly. “What the president is doing up at the top will be a little different; he’s more different than any president we’ve had. But what’s happening at the ground level is going on just as you’d expect it would be. So it should be a smooth transition, even if the public view is anything but that.”

Theda Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology, characterized the election as a culmination of two grassroots movements: the Tea Party, created in response to Barack Obama’s election, and a strengthened progressive movement in response to Trump. “Activism helped to raise the moral stakes that we saw come to a clash in this election — in which both sides felt that the very nature of America, its past and its future, were on the ballot. I do not think that this was an economically determined election.”

Responding to an audience question, Skocpol named ways that Biden could make a constructive difference: by engaging with civic and citizen groups and police to address criminal justice after the George Floyd incident and by enacting the “infrastructure week” that Trump promised. Still, she warned that extremists on the right wing — both the “top-down, ultra-free-market, billionaire-backed” faction pushing for tax cuts and the “Christian nationalist and ethno-nationalist forces,” which resist racial and immigration-fueled social changes, will oppose him at every turn. “Both of those forces will keep many elected Republicans from cooperating with a lot of what a moderate Democrat will want to do — no matter how good Joe Biden is at schmoozing with people he’s known for all his life.”