Illustration by Ben Boothman

Imagine a world in which AI is in your home, at work, everywhere

AI+Art project prompts us to envision how the technology will change our lives

Fourth and last in a series that taps the expertise of the Harvard community to examine the promise and potential pitfalls of the rising age of artificial intelligence and machine learning, and how to humanize them.

Imagine a robot trained to think, respond, and behave using you as a model. Now imagine it assuming one of your roles in life, at home or perhaps at work. Would you trust it to do the right thing in a morally fraught situation?

That’s a question worth pondering as artificial intelligence increasingly becomes part of our everyday lives, from helping us navigate city streets to selecting a movie or song we might enjoy — services that have gotten more use in this era of social distancing. It’s playing an even larger cultural role with its use in systems for elections, policing, and health care.

But the conversation around AI has been held largely in technical circles and focused on barriers to advances or use in ethically thorny areas — think self-driving cars. Sarah Newman and her colleagues at metaLAB(at)Harvard, however, think it’s time to get everyone involved, and that’s why they created the AI+Art project in 2017 to get people talking and thinking about how it may impact our lives in the future.

Newman, metaLAB’s director of art and education and the AI+Art project lead, developed the Moral Labyrinth, a walkable maze whose pathways are defined by questions — like whether we’re really the best role model for robot behavior — designed to provoke thought about our readiness for the proliferation of the increasingly powerful technology.

“We’re in a time when asking questions is of paramount importance,” said Newman, who is also a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. “I think people are refreshed to encounter the humanities and arts perspectives on topics that can be both technical and elitist.”

MetaLAB is part of the Berkman Klein Center and its AI work has been developed alongside the Center’s Ethics and Governance of AI Initiative, which was launched in 2017 to examine the ongoing, widespread adoption of autonomous systems in society.

Recent metaLAB exhibits include “Curricle,” “Moral Labyrinth,” “The Future of Secrets,” and “The Laughing Room.”

Kris Snibbe and Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photos; courtesy photos from metaLAB

Jonathan Zittrain, Berkman Klein Center director and Harvard Law School’s George Bemis Professor of International Law, said it’s important that we think hard about whether and where AI’s adoption might be a good thing and, if so, how best to proceed.

Zittrain said that AI’s spread is different from prior waves of technology because AI shifts the decision-making away from humans and toward machines and their programmers. And, where technologies like the internet were developed largely in the open by government and academia, the frontiers of AI are being pushed forward largely by private corporations, which shield the business secrets of how their technologies operate.

The effort to understand AI’s place in society and its impact on all of our lives — not to mention whether and how it should be regulated — will take input from all areas of society, Zittrain said.

“It’s almost a social-cultural question, and we have to recognize that, with the issues involved, it’s everybody’s responsibility to think it through.”

— Jonathan Zittrain, Berkman Klein Center director and Harvard Law School’s George Bemis Professor of International Law

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Over the past three years, metaLAB’s scholars and artists have been at work encouraging that thought. They have created 18 different art installations on AI themes, which so far have been exhibited 55 times in 12 countries and inspired more than two dozen articles.

In addition, project artists have presented more than 60 public lectures, developed and presented 12 workshops and courses, including brainstorming sessions for Berkman Klein’s Assembly Fellowships, and courses at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, led by metaLAB Faculty Director Jeffrey Schnapp.

“I think people are refreshed to encounter the humanities and arts perspectives on topics that can be both technical and elitist.”

— Sarah Newman, metaLAB’s director of art and education and a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

While the COVID-19 outbreak disrupted physical installations planned for the spring and summer, Newman said the disruption forced those involved to rethink their plans, their approaches, and even the concepts behind their artwork, workshops, and other interactions. Before the pandemic, most of the pieces were conceived as in-person experiences in which visitors interact with AI in ways that provoke thought.

Since COVID, Newman said, activity has been forced online, which broadens the reach of the project to physically distant audiences and highlights that there are more ways to experience art than being in its physical presence. And whether virtually or in person, engagement is valuable in the society-wide conversation, Newman said, because it generates different approaches and brings in different audiences than traditional scientific or technological activities.

When people explore an artistic work, they feel freer to ask questions prompted by a feeling or an assumption, and the art itself can ask questions that don’t necessarily have answers, at least not simple ones.

“It’s a different way to engage and taps into different sensibilities and possibly insights,” Newman said.

Among metaLAB’s AI+Art projects have been an AI-generated “The Laughing Room,” developed by Jonny Sun and Hannah Davis. That exhibit is arranged to resemble a television sitcom set and is complete with an eavesdropping AI that plays a laugh track anytime someone in the room says something its algorithm deems funny.

Kim Albrecht, metaLAB’s data visualization designer, has created installations that highlight the stark differences between how machines and humans view the world. One, called “Artificial Senses,” displays data from sensors common in our devices, such as smartphones and laptops, including cameras, microphones, geographic locators, accelerometers, compasses, and touchscreens. The resulting visualizations are linear, multicolored or multishaded, and bear little resemblance to what we see when we use a map, listen to audio, or tap to open an application.

“There’s this comparison between us and the machines — our brains are often talked about as ‘computers’ — but I wanted to point out [that] these machines really have a very different sense of their surroundings that is totally driven by the data,” Albrecht said.

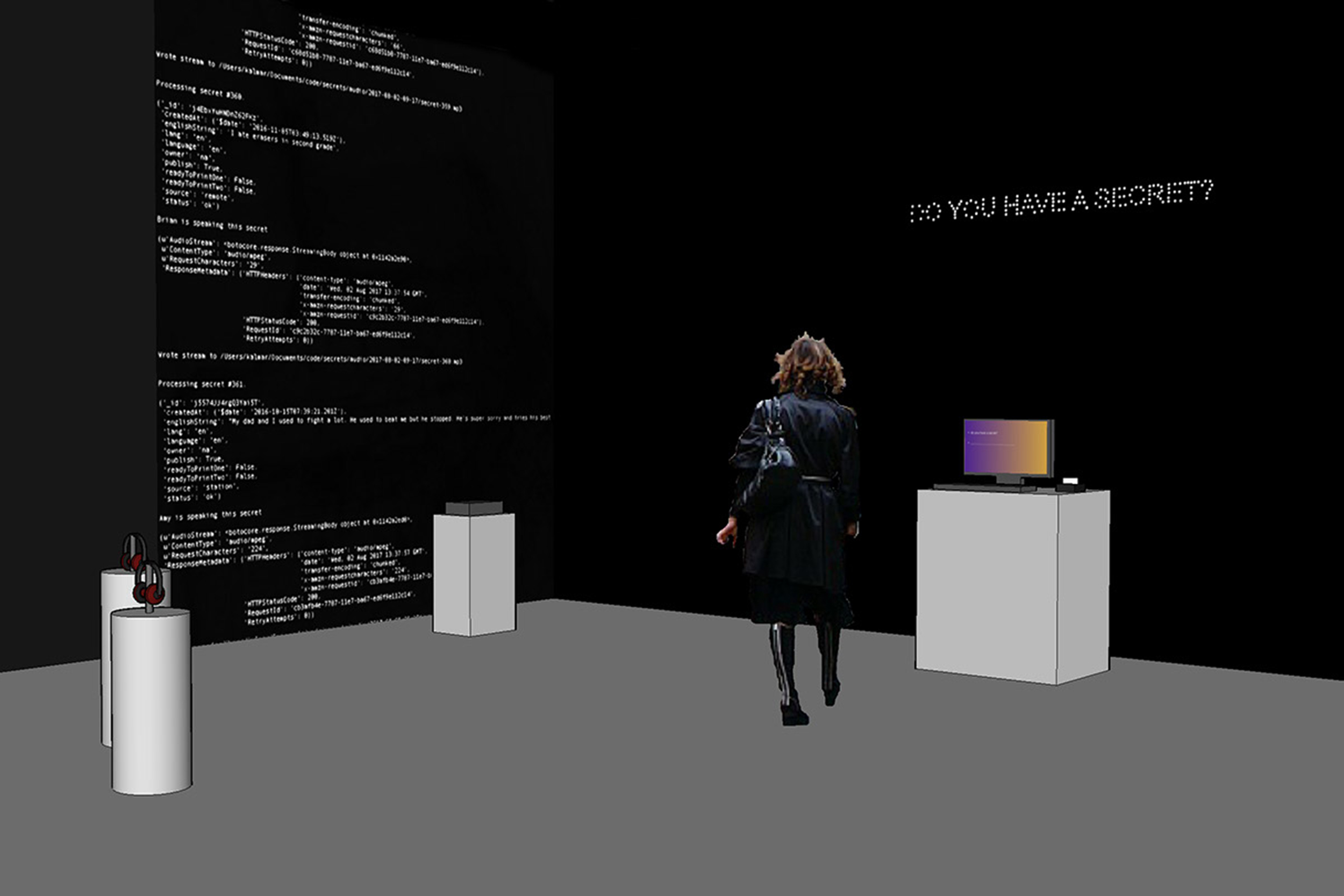

One pre-COVID installation called “The Future of Secrets” was at Northeastern University’s School of Law in September 2019. “The Future of Secrets” was developed by Newman, Jessica Yurkofsky, and Rachel Kalmar and presents visitors with a simple interface — a laptop on a pedestal — that asks them: “Do you have a secret? Type it here.” When they do, a nearby printer starts up and prints the secret of an earlier visitor for them to read. Newman said people react in surprise as they read the secret and the truth settles in that their own secret will be shared with a stranger, perhaps someone in the room.

“There seems to be a level of surprise when they get someone else’s secret, like [they’re thinking], ‘Oh, can I get mine back?’ But it relates to how we use technology all the time. We don’t own our data, and we don’t control it,” Newman said. “We conduct transactions with all this private information, and it’s not just about our finances, our bank statements, but our love lives, everything. The secret that the installation returns is programmed by an algorithm that the visitors don’t understand, but it seems to know more about them than they’d expect.”

Newman’s Moral Labyrinth has undergone an evolution since COVID-19 arrived. She had planned a spring workshop to generate new questions for the labyrinth, but the pandemic forced it online. The event filled up and included participants from other countries, with the resulting questions reflecting all the differing perspectives as well as current hot-button social issues around public health and social justice.

“It was unbelievable to have such broad participation, and in that way it was better,” Newman said.

The shift forced a change in the art itself. While the original labyrinth was a walkable maze in a physical gallery, the newly conceived one will be 3D, virtual, and online. Once it’s completed it will be possible to print it out as a stencil and use it as public art in locations around the world.

“I thought, ‘I can’t make one thing that everyone can come together and experience, so why not bring everyone together to make art that will go back out into the world,’” Newman said. “Hopefully there’ll be a lot of labyrinths.”

While Newman thinks it’s imperative that critical conversations about AI occur, she doesn’t count herself an alarmist. The most troubling things we’re seeing now, she said, involve how societal and historical biases are replicated in machine-learning models. There are additional risks associated with how the technologies get developed, but new innovation often triggers cultural concerns and evolving solutions. Even something as commonplace today as electricity was initially unregulated and dangerous, until someone realized you couldn’t just string bare wires everyplace.

Albrecht agrees, saying that problems are likely to crop up not because of broad, society-wide adoption of AI technology — which he sees as potentially as transformative as industrialization — but here and there, in particular applications whose faults will spur regulation or other action to address the problem.

“AI will affect everybody,” Newman said. “It’s important to have diverse participation in the conversation. I think it’s borderline dangerous not to have historians, philosophers, ethicists, and artists at the table.”