The star chemist

How Mireille Kamariza pursued the fantastical to solve a deadly health problem

In 2017, while still a graduate student, Fortune magazine named Mireille Kamariza one of the World’s Most Powerful Women.

Courtesy of Mireille Kamariza

Growing up in Bujumbura, Burundi, Mireille Kamariza didn’t know any astronomers, or any scientists at all for that matter. But she adored planets anyway. At the start of every school year, she and her fellow students would wrap up their notebooks to protect them from wear. And every year, Kamariza hunted her town for magazines with glossy pictures of planets, astronauts, and “any news about astronomy.” Between classes, she stared at those astronomical covers like they were portals to a fantastical world.

The Junior Fellow never ended up floating among the stars, at least not in a literal sense. This August, Chemical & Engineering News named her one of its Talented 12 for her invention of a quick, low-cost test to detect tuberculosis. In 2017, Fortune magazine named her one of the World’s Most Powerful Women while she was still a graduate student. In 2018, she earned an even rarer title: co-founder of a company in the male-dominated biotech industry. In a way, the world she now inhabits — that of an award-winning scientist, Silicon Valley biotech entrepreneur, degree recipient from the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University — was a fantastical world, at least to that young girl in Burundi who got lost in pictures of Mars and Venus.

“It feels like a different life,” Kamariza said, “It’s nothing short of a miracle that I’m one of the few that was able to make that jump.”

After achieving the fantastical, Kamariza is tackling a very real problem: Throughout the developing world, including Burundi, tuberculosis is one of the top causes of death. In 2018, the disease killed 1.5 million worldwide, far more than even AIDS. Though testing and treatment are on the rise, low-income, rural populations still struggle to detect and contain the disease (especially now that COVID-19 diagnostics are prioritized over every other infectious disease). Each year, about 10 million people develop tuberculosis and about 3 million go undetected, Kamariza said. Her invention — a portable diagnostic tool — could help identify more cases faster, anywhere in the world, to prevent further spread, get treatment to those in need, and even monitor the effectiveness of that treatment.

“A lot of people doing TB work were rewired to do COVID work. TB patients are being left behind.”

Mireille Kamariza, Junior Fellow

When Kamariza arrived in the U.S., settling in San Diego at age 17, science was still an alien thing. She spoke French but little English (she watched “Star Wars” and “Star Trek” to learn more); she shared a studio apartment with her two older brothers and worked part-time at Safeway while taking classes full-time at San Diego Mesa College. There, she left her love of planets behind: “How many astronauts do you know that started at a community college?” she said.

By chance, she enrolled in a chemistry course with Professor Saloua Saidane, who happened to speak French. She guided Kamariza over the language barrier before pushing her to transfer to the University of California, San Diego. Kamariza needed the encouragement: Other mentors told her, bluntly, that her English and G.P.A. were too poor for her to make it to UCSD. They were wrong.

Once at UCSD, Kamariza again doubted her ability to make it to graduate school. But Tracy Johnson — another chemist and the first Black woman scientist Kamariza encountered — pushed her to apply to the University of California, Berkeley. “I would never make it to UC Berkeley in a million years!” Kamariza said to Johnson. “Look at all the people who make it in. How many are African immigrants?”

Kamariza often credits external interventions like miracles, luck, and mentors for her success. “For immigrants, for people who come from backgrounds that are traditionally underserved,” she said, “it’s all about opportunities and it’s about who can open the door for you.” Still, though Johnson showed her the door, Kamariza knocked. To her surprise (but not Johnson’s), she got in.

At Berkeley, Kamariza joined Carolyn Bertozzi’s chemical biology lab. There, and continuing at Stanford University, she combined her knowledge of chemistry and molecular biology to eventually invent her tuberculosis diagnostic. Her test turned what used to be an 11-step process into one simple step. “Because it’s stable and because it doesn’t require a fridge to work,” Kamariza said, “you could in principle do this experiment anywhere. You could be in the tundra of Alaska or the desert of Namibia and do it.”

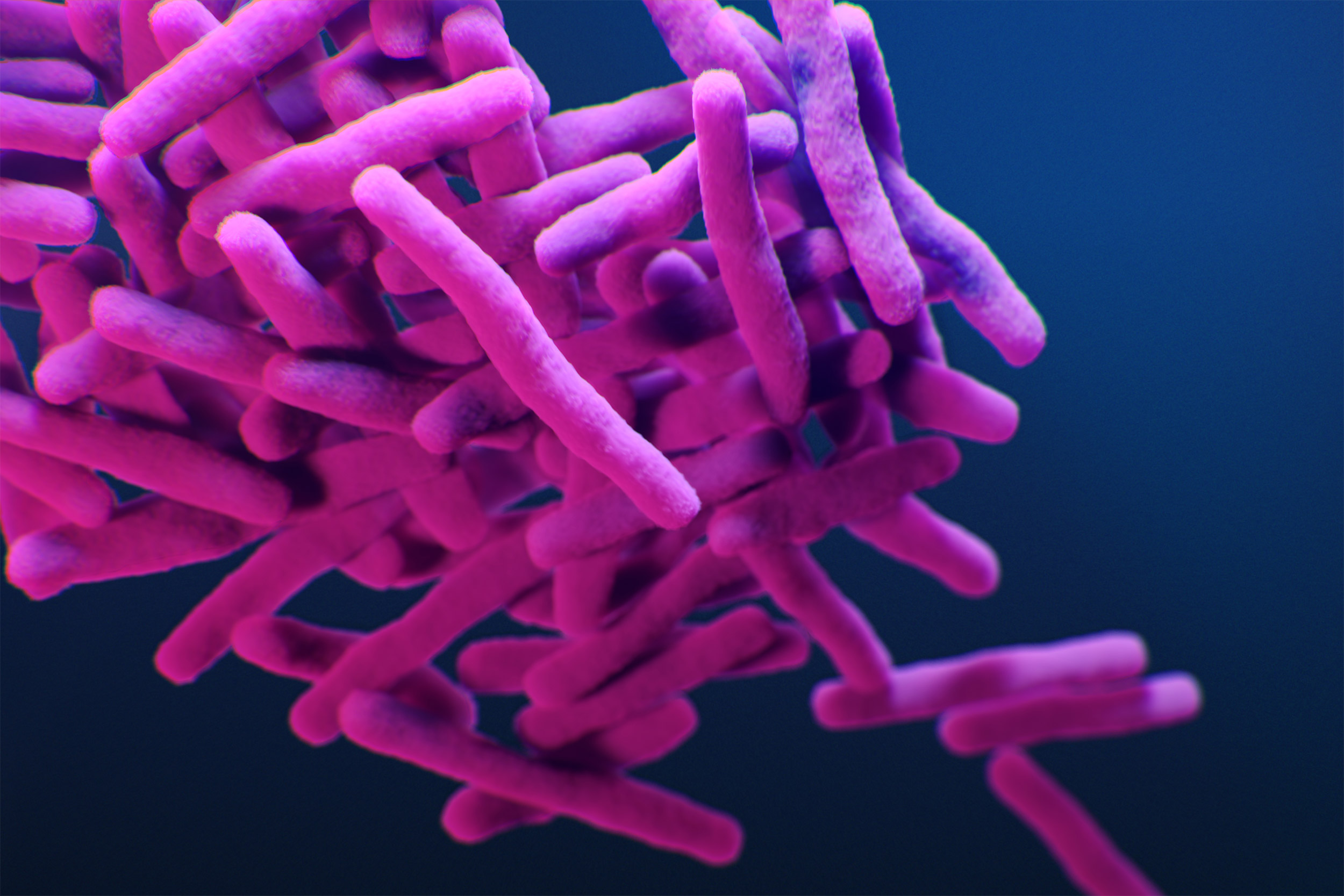

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacteria with a cell wall thick enough to block out most drugs. Mireille Kamariza designed a molecule that embeds into that wall and lights up — researchers only need a microscope and a reagent to see it.

Photo by Fred Tomlin

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacteria with a cell wall thick enough to block out most drugs. Kamariza she designed a molecule that embeds into that wall and lights up — researchers only need a microscope and a reagent to see that tuberculosis is present and alive. Since her molecule ignores dead tuberculosis cells, the test can tell researchers far more about the bacteria’s reaction to certain environments and treatments. Over time, they can monitor a patient’s blood to see whether a drug kills the bacteria, and how quickly. Since results come back within a couple hours, as opposed to the month and a half that current tests require, the tool could detect and track cases and treatments far more effectively.

“It was quite a day when we realized it was working,” Kamariza said. “I immediately went to the medical applications.” She was anxious to get the tool to market as quickly and safely as possible because, as she said, “I know people need it.”

Bertozzi encouraged Kamariza to launch her own company. Once again, she wavered. “How many African immigrant women founders do you know in Silicon Valley in the biotech industry?” Kamariza said. “I think it’s a flat zero.”

She makes at least one. In 2018, Kamariza co-founded OliLux Biosciences. The same year, Harvard offered her a position in its Society of Fellows (another offer she never thought she’d receive).

“I’m the first Black woman biologist at the society,” Kamariza said. “At that point, it’s not about me anymore. It’s what I represent. It’s about people who come after me. It’s breaking a glass ceiling. It was an offer I could not refuse.”

In the summer of 2019, she headed off to Cambridge and focused her efforts on diversifying the European-dominant genetic pool on which global precision medicine is based.

“For immigrants, for people who come from backgrounds that are traditionally underserved, it’s all about opportunities …”

Mireille Kamariza

“If people you’re recruiting are not diverse enough then you don’t know how [a drug] is going to affect people at large,” she said. “All this leads to, of course, health disparities here in the U.S. But quite broadly, there are entire sub-continents and entire countries that you’re leaving out.”

In the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic floodlit the longstanding, systemic health inequities that put vulnerable communities at increased risk. But those disparities extend well beyond the U.S. and in different ways: When the pandemic hit, Kamariza’s tuberculosis work halted. Borders closed. Pilot projects stopped. Tuberculosis-positive patients were forced to quarantine with family, potentially spreading the disease in the name of preventing another. Efforts on diagnostics focused almost exclusively on tracking COVID-19.

“A lot of people doing TB work were rewired to do COVID work,” Kamariza said. “TB patients are being left behind.”

More like this

In the U.S., most people don’t see tuberculosis as a threat, especially now. “People talk about diabetes and all these other complex, metabolic diseases. Rarely do people talk about infectious diseases,” Kamariza said. “Whereas, the places that I have my eye on, this is the reality every day.” Even during the pandemic, OliLux continues to focus on tuberculosis, hoping to get tests out to places like Indonesia, Singapore, and South Africa.

On top of everything else, Kamariza tries to keep up with social media, to be “visible,” she said, and make sure young scientists, who pore over pictures of planets or whatever else captures their imagination, see that she achieved the fantastical, and they can, too. “It stops being about me,” she said. “It really does become about the history and the legacy of what we as human beings are doing.”