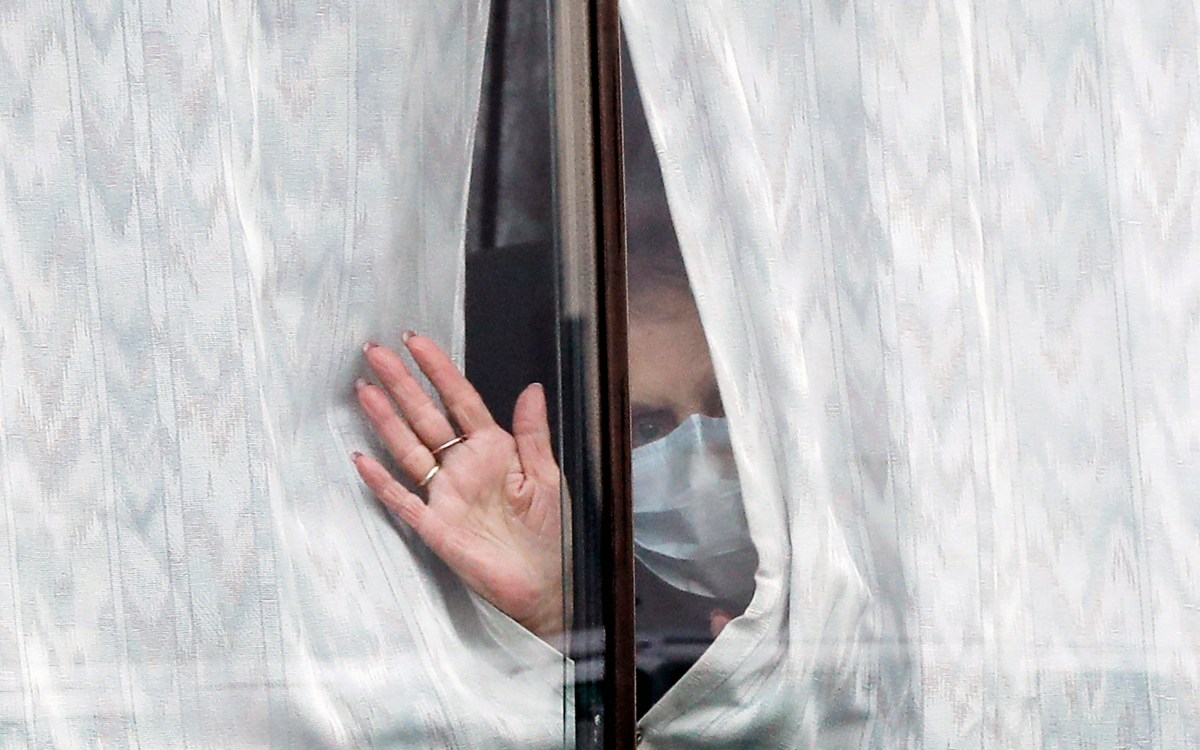

Deans discuss the changes and challenges during a pandemic. Bharat Anand (clockwise from left, middle row), Amanda Claybaugh, Dan Levy, Bridget Terry Long, and Srikant Datar.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Lessons from teaching in COVID times

Deans detail best practices that emerged over time

The pandemic has transformed education at Harvard, requiring students and faculty to innovate with online learning. During a Tuesday plenary, deans from across campus looked back on the year with a sense of achievement — and a bit of fatigue as well.

“This could have been a disaster, but instead you collectively have turned this into a tremendous opportunity for the University,” Provost Alan Garber told the members of Tuesday’s panel, “Teaching and Learning at Harvard: Looking Back, Looking Forward.” This was the first of six virtual panels in a three-day series, “Teaching in Unprecedented Times,” presented by the Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning in partnership with Teaching and Learning Centers.

Garber compared the faculty and staff’s efforts over the past year to impossible challenges sometimes given to test the limits of engineering students, such as building a robot out of string and marshmallows. Because faculty have proven so resourceful, he said, “The future of education at Harvard is brighter than it would have been without the pandemic.”

Moderator Bharat Anand, vice provost for advances in learning, asked each of the panelists to share key lessons from the past nine months.

“It’s fair to say we have appreciated teaching in person more than ever, and we realize how much of a profoundly human experience this was,” said Dan Levy, a senior lecturer in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School who this year published “Teaching Effectively With Zoom.” He praised the creativity that faculty showed in reimagining their classes, but admitted that teaching and learning online can be tiring. “It was simply exhausting for most of us. Zoom fatigue and screen fatigue are real. Taking one course online is not the same as taking all of them online in the midst of a pandemic, and I don’t think we’ve recognized that fully.”

“It’s fair to say we have appreciated teaching in person more than ever, and we realize how much of a profoundly human experience this was.”

Dan Levy, Harvard Kennedy School

Bridget Terry Long, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, added that hers was one of the first Schools to commit to remote learning for the entire year, which give them a head start in redesigning courses. Just as important, she said, was that the models for student support also got a second look. She cited the creation of “student success teams” that drew staff and faculty from across the School to support students in the face of the pandemic, racial inequities, and impending recession. Also, admissions was opened to candidates who would not have been able to come to Cambridge. “We started to see this as an opportunity to build something new, rather than feeling that we were compromising.”

Amanda Claybaugh, dean of undergraduate education, noted that the Faculty of Arts and Sciences drew some early criticism for going remote but that the decision proved to be the right one. “The FAS has been very conservative, first about our ability to offer in-person learning, then our decisions about how many students to bring to campus. As our peer institutions had to walk back their more ambitious plans, we felt it was more important to give our students whatever certainty we could give them.”

Making the call early left plenty of time to ensure that faculty could receive training in remote teaching. “This meant that more than 1,000 instructors did weeklong training over the summer. We could say to them, ‘If you make this small set of changes, it will have a big impact on your course.’”

Students, she said, occasionally complained that they were being asked to do too much work or that professors were always contacting them. “These are good problems,” she said. “We see that as a success.”

Srikant Datar, faculty dean at Harvard Business School (HBS), discussed the challenges presented by teaching case method online, without the live discussions and breakout rooms to which students were accustomed. HBS approached this by recruiting “online learning facilitators” — staff members from across the School who supported faculty — and by devoting a week to mock classes for practice. Since many students were on campus, they also experimented successfully with a socially distanced hybrid classroom. This led to the problem of virtual students feeling left out, which was solved by rotating students between the live and virtual settings. Above all, he said, HBS benefits from its willingness to experiment.

Looking forward, the panelists said that current innovations will leave a positive mark on post-COVID education. One likely result will be larger, more diverse hybrid classrooms. Datar said that these would likely include postgrad students. “It would be fabulous if alumni could increase the class size just by coming online — but increase it in a way that their contributions would be extremely valuable because they’re older and know certain things that our students would benefit from learning. But can [class size] go even larger, like double or triple? Those would be interesting experiments to try.”

As the pandemic persists, Claybaugh pointed out that many students are still yearning for more personal interaction. “One thing we’ve learned from students is that they like to be put into different breakout rooms, because they just want to meet other students. They’re able to maintain ties with their close circle of friends, but they want that casual interaction reproduced. The College is trying to do that socially, but that’s where Zoom fatigue sets in.” she said. “Once they’ve done all their schoolwork on a screen they don’t then want to socialize on a screen. And that’s a real challenge. When they write to me and say, ‘What will you do to enable us to socialize?’ I always say, ‘You don’t want what a 50-year-old lady thinks you should do.’ I hope this is a time for young people to figure out new ways to interact online.”