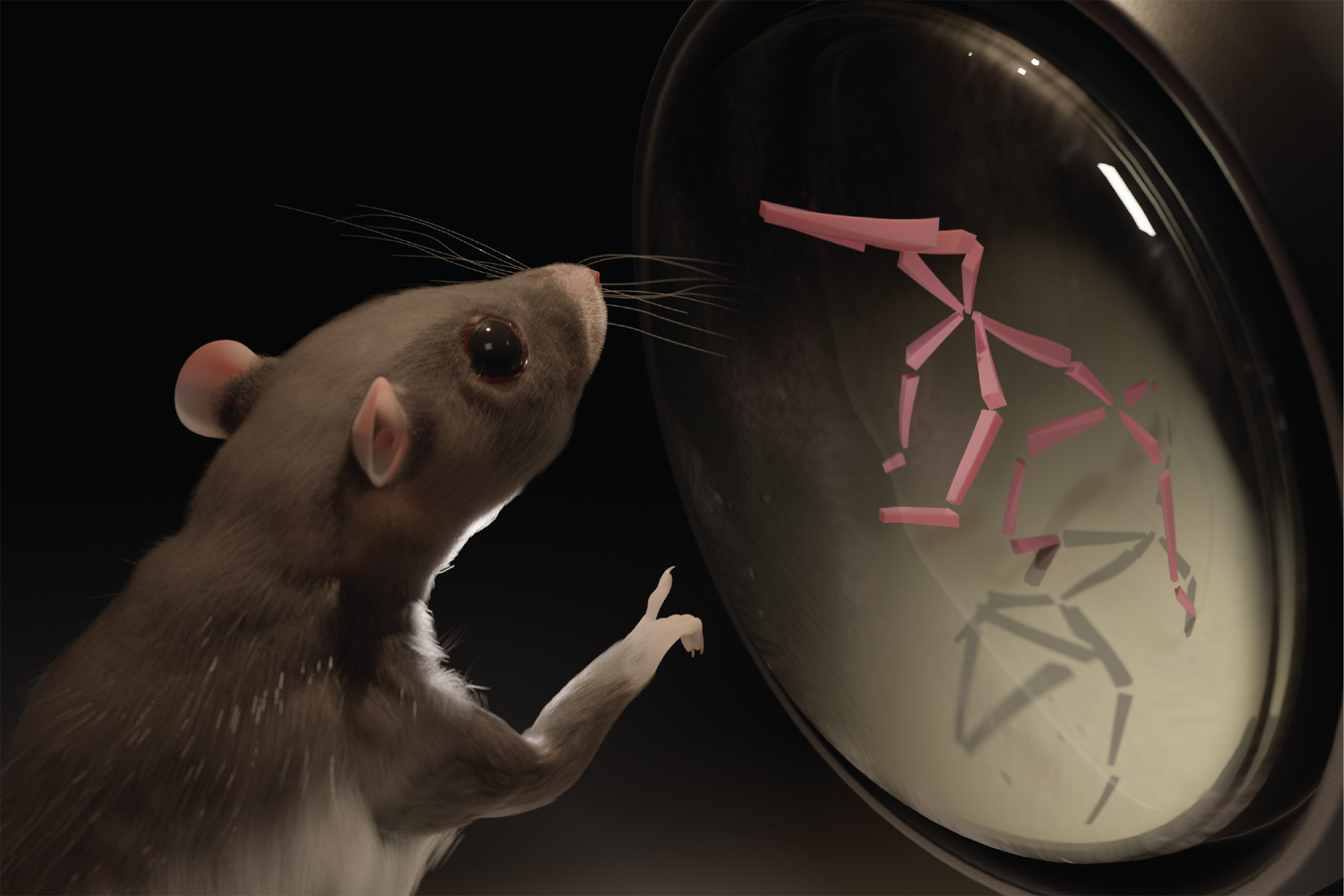

An artist’s interpretation of CAPTURE.

All images courtesy of K.J. Herrera, J.D. Marshall, B.P. Olveczky

CAPTURE-ing movement in freely behaving animals

New behavioral-monitoring system combines motion capture, deep learning

Scientists studying the movement of animals have longed for a motion-capture method similar to the one Hollywood animators use to create spectacular big-screen villains (think Thanos in “The Avengers”).

Now a team of Harvard-led scientists has made a breakthrough, assembling a new system combining motion capture and deep learning to continuously track the 3D movements of freely behaving animals. The project, which monitors how the brain controls behavior, has the potential to help combat human disease or advance the creation of artificial intelligence.

The system, called continuous appendicular and postural tracking using retroreflector embedding — CAPTURE, for short — delivers what’s believed to be an unprecedented look at how animals move and behave naturally. This can one day lead to new understandings of how the brain functions.

“It’s really a technique that will end up informing a lot of neuroscience, psychology, drug discovery, [and disciplines] where questions of behavioral characterization and phenotyping are important,” said Bence Ölveczky, a professor in the Harvard Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

Up to now, no technology has captured intricate details of an animal’s natural behavior for extended periods of time. Recording precise animal movements during simple tasks, like pressing a lever, is possible, but because of the limited range of movements and behaviors scientists have been able to explore, it isn’t clear if the insights gained can lead to a general understanding of brain function.

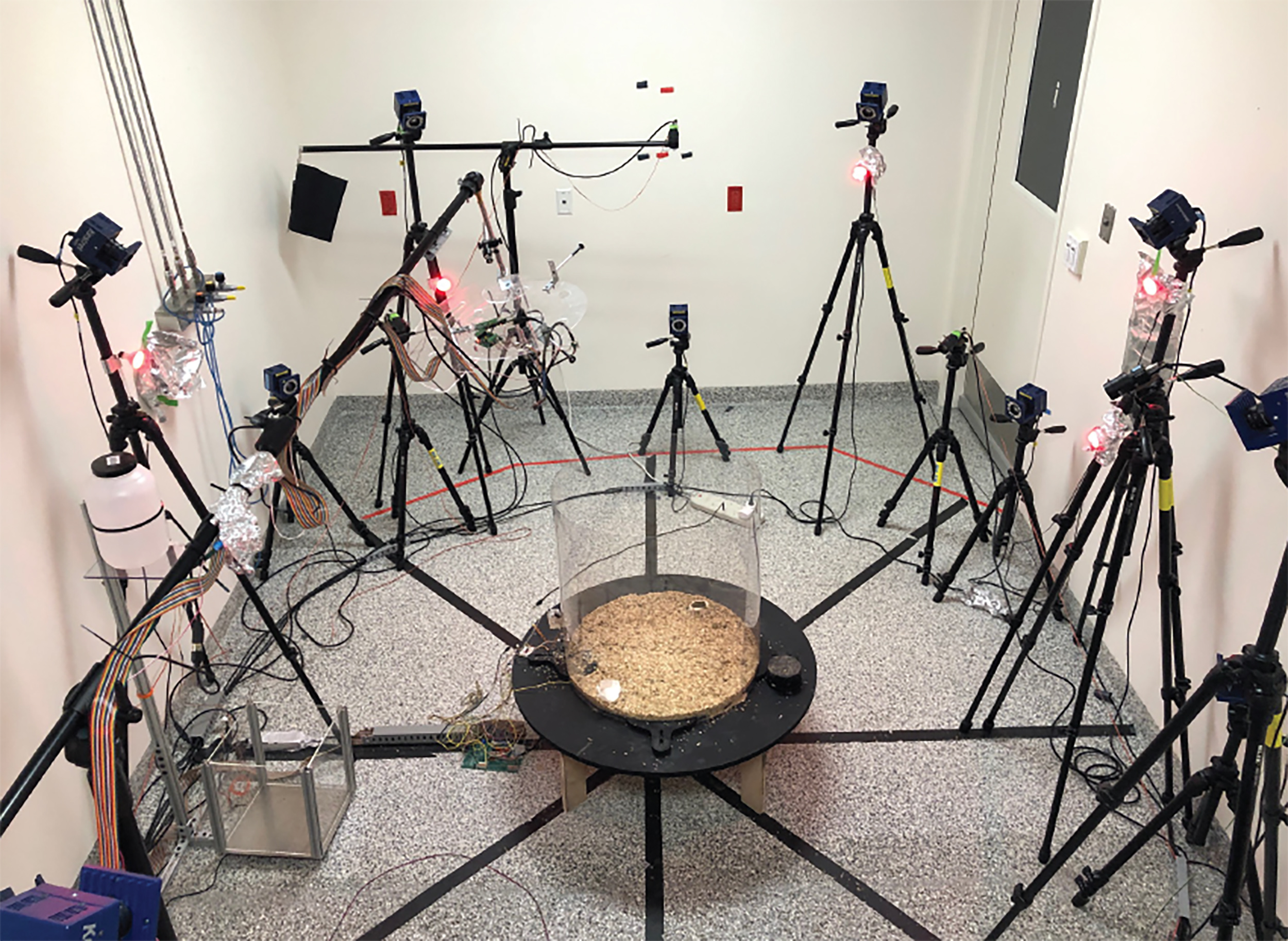

CAPTURE starts the push beyond those limitations. It uses a series of custom markers that are attached to an animal, like tiny earrings, to track the position of the animal’s whole body nonstop with a 12-camera array. This lets them digitally reconstruct the animal’s skeletal pose and measure its normal movements for weeks at a time. With that data, the scientists can then develop new algorithms to create a foundational map of an animal’s normal behaviors. These behavioral maps can then be compared with maps when the animal is in an altered state, giving researchers an exact look at even some of the most subtle differences.

CAPTURE is described in a study recently published in Neuron. Harvard postdoctoral fellow Jesse Marshall led the project. Working with him and Ölveczky were William Wang ’20 and Diego E. Aldarondo, a student at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Right now, CAPTURE has been designed to work only on rats, but the team plans to expand to other animals in the future.

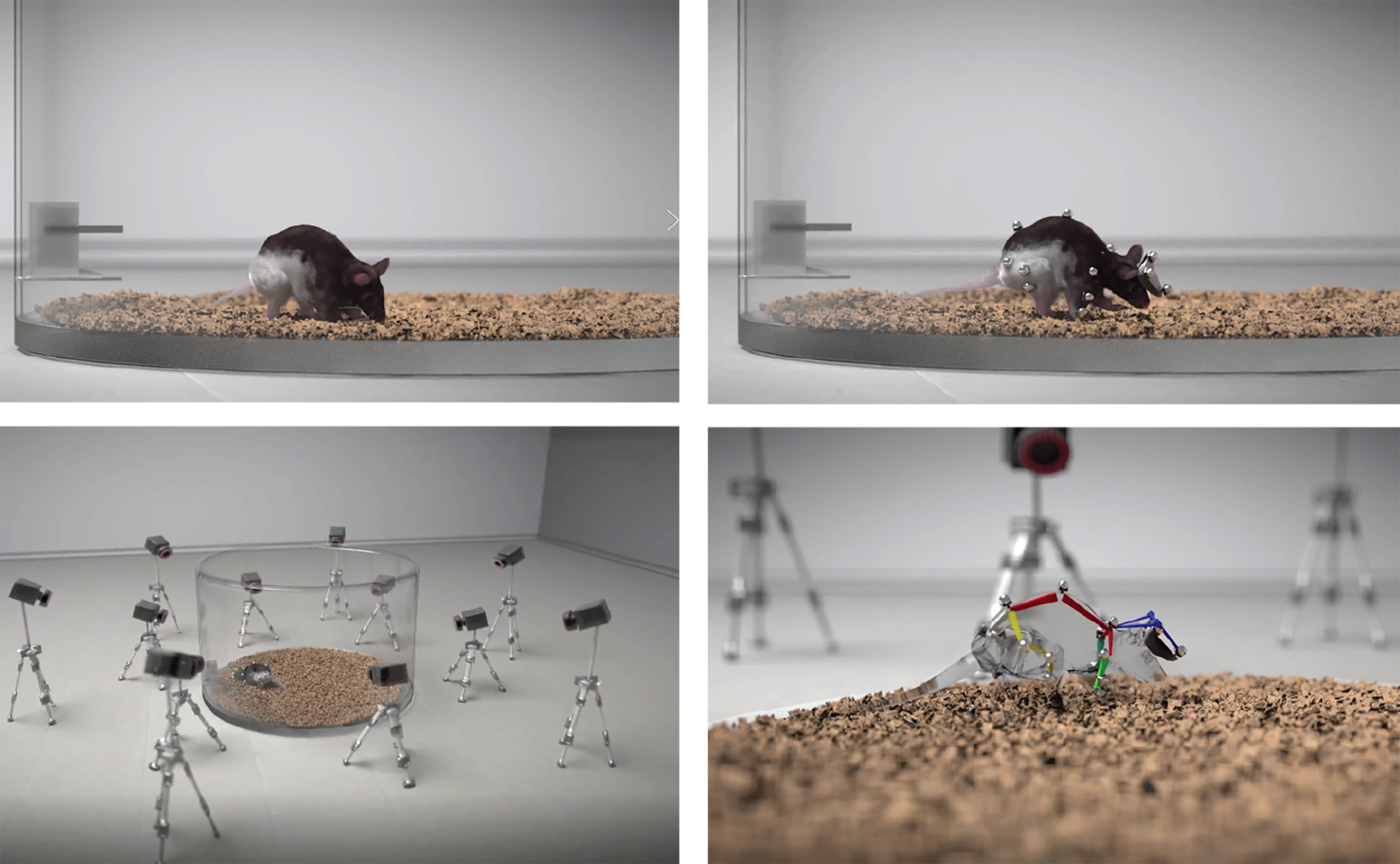

Researchers attached markers to the mouse and let it actively explore a large arena (top). They then used a 12-camera array to track the position of the markers (lower left) and reconstruct the animal’s pose (right). A photograph of the actual CAPTURE recording arena.

“The large camera array works the way you would track actors for making Gollum [in the ‘Lord of the Rings’] or other types of animation,” Marshall said. “We use it to precisely measure the position of their head and limbs and then there’s a lot of analysis on top of that that enables the detection of behaviors and the isolation of other components [like behavioral organization].”

Marshall spent months researching the constraints and advantages of existing movement technologies before settling on motion capture. He then spent six months figuring out what type of marker would stay attached for long periods of time.

“Traditional markers from Hollywood are made of foam, and that wasn’t going to fly with rats,” Marshall said.

Working with local veterinarians, the team designed custom body piercings made of specialized reflective glass and attached them to 20 locations on the rats’ bodies. With the markers in place, they let the rats explore a naturalistic area and tracked their movements using the cameras 24/7 for weeks.

The researchers mapped out natural behaviors such as grooming, rearing, and walking and showed how those movements are organized into structured patterns, like the arrangement of words into sentences.

The team then looked at how those behaviors and patterns changed in response to two stimulants, caffeine and amphetamine. As expected, both drugs caused the rats to move around more, but they did so in different ways. Caffeine amped them up, but they explored their cage normally. Amphetamine, on the other hand, shifted their behavior in novel ways and made them quite disturbed, Marshall said. They ran around in repeated, sequential patterns.

When the team studied rats with a form of autism, the data showed another surprise.

The scientists saw the rats perform abnormal grooming patterns that hadn’t been described before. Grooming pattern alterations could be an important indicator used to model repetitive movements observed in people with autism, but they traditionally have been difficult to measure. The scientists say detecting these types of subtle and precise behavioral deficits are important in getting a better handle on many diseases and could be one of the prime uses of CAPTURE.

Other efforts to expand CAPTURE include combining their data with recordings of neural activity to map the relationship between brain signals and behavior across the full set of natural movements a rat performs. They are also working with Google DeepMind to use CAPTURE to help model how the brain produces behavior, and potentially to make new advances in artificial intelligence.

“We’re only going to go deeper,” Marshall said.

This research was supported with funding from the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Segal Family Foundation.