T.S. Eliot in London circa early 1920s.

Courtesy of Houghton Library

Let us listen then, you and I

Woodberry Poetry Room marks its 90th anniversary with online readings by contemporary greats and older recordings by T.S. Eliot

There’s a certain magic to poetry read aloud, and if it is recited by the writer, listeners gain insights into the work that are difficult to come by any other way.

It is only fitting, therefore, that the George Edward Woodberry Poetry Room would kick off the celebration of its 90th anniversary next week with online readings by such contemporary greats as Sonia Sanchez, Tongo Eisen-Martin, Anne Boyer, and Claudia Rankine. And that the special collection, one of the earliest and largest audio-visual archives for literary sound recordings in the country, will look back on its nine decades by making some of its first recordings — of the poet T.S. Eliot reading his own work — available to the general public on Friday (March 19).

“We are immensely grateful to the T.S. Eliot estate for so generously granting us permission to make Eliot’s earliest known poetry recording available for the first time in more than half a century,” said Christina Davis, curator of the poetry room. That recording of Eliot 1910, A.M. 1911, Litt.D. ’47, reading “The Hollow Men” and “Gerontion,” dates back to the poet’s Charles Eliot Norton lectures in 1932–33, when the Woodberry collection had just been launched.

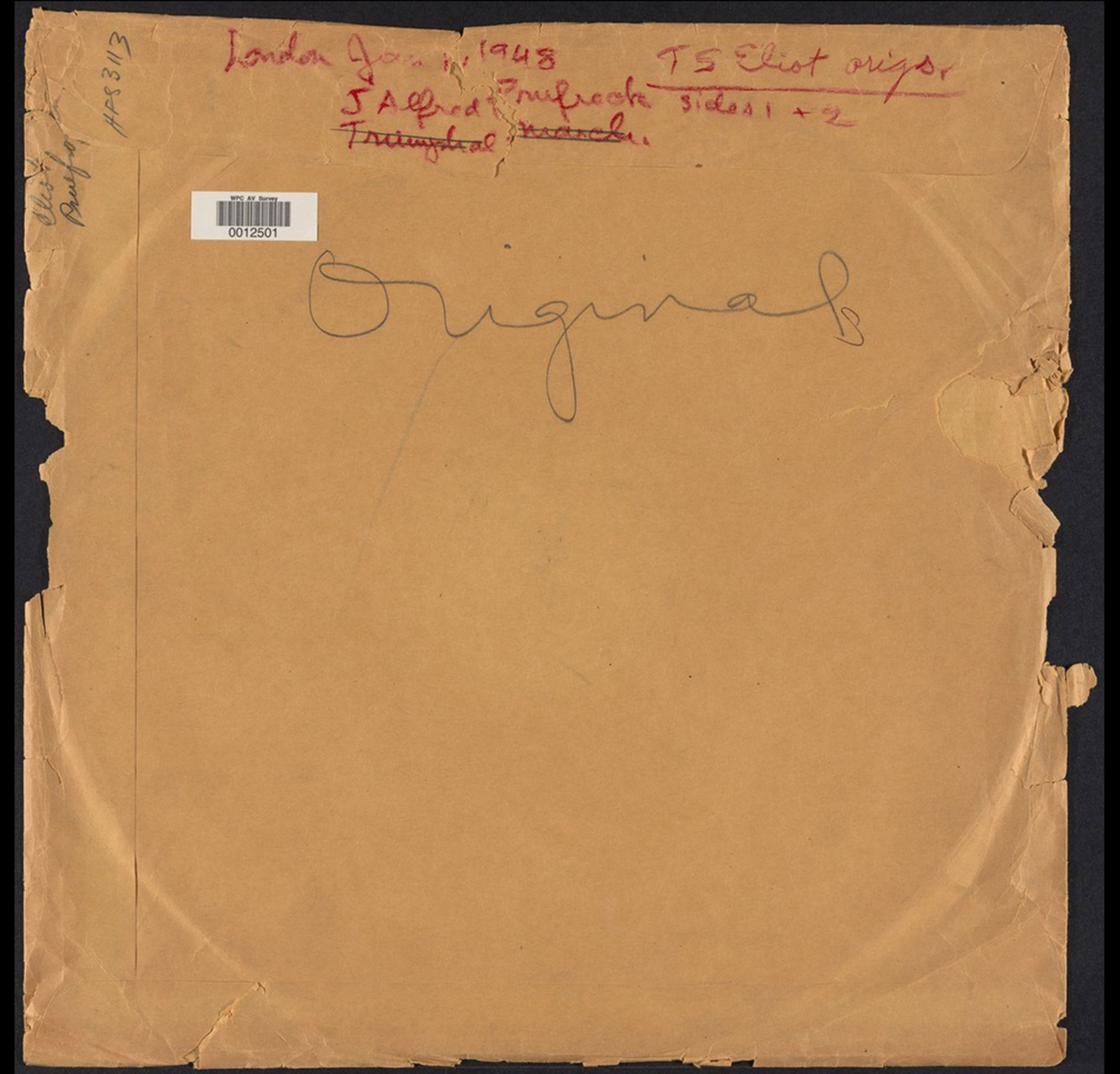

Created by recording pioneer Frederick C. Packard Jr., who used a variety of studios on campus, the two-poem recital was originally released on Packard’s Harvard Vocarium label in 1933 and later compiled onto a long-playing disc in 1951. Along with a recording of a complete live reading Eliot gave at Sanders Theatre in 1947, it will be accessible on the University’s In Focus page starting tomorrow, in advance of World Poetry Week. (Both recordings will also ultimately be made available via the HOLLIS online catalog and the Poetry Room’s online Listening Booth.)

“I am delighted that T.S. Eliot’s Harvard readings are being released to mark the 90th anniversary of the Woodberry Poetry Room, not only because of the relative rarity of recordings of Eliot reading his work, but because they were recorded at his old college, which he continued to think of with such affection throughout his life,” said Clare Reihill, trustee of the T.S. Eliot estate.

T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men” on the turntable in Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard.

Courtesy of Woodberry Poetry Room

That these recordings survive is noteworthy. The first, which was most likely pressed on shellac, was particularly fragile. “There’s a long history of recordings being broken in transit,” noted Davis.

Recorded during the Depression and then in the aftermath of World War II, together these recordings resonate today. “These were arguably equally challenging times,” said Davis. “But also, at the same time as inspiring and galvanizing technological changes in broadcasting were being made, which opened up these pathways of global communication similar to what we’re experiencing today.”

Eliot, said Davis, was an ideal subject for those early recordings. “His reading voice really developed then, as did a lot of the modernist poets’ over that period.” Calling him “the rock star of his period,” she said, “You begin to hear him building that capacity in this 1947 reading at Sanders Theatre.”

To Reihill, the passage of time between the two recordings is apparent. “The value of these recordings lies primarily in the document they provide of a poet’s encounter with work written by his younger self, a self which appears now a stranger to him,” she said. “As Eliot says in his opening remarks to the 1947 recording: They feel as though they were by someone else,” Reihill continued. “In his voice, I think, one can hear a sort of resigned sadness tinged with self-deprecation.”

Of course, a live reading, like the 1947 Sanders recording, involves more than the poet. “The audience is half of the experience,” said Davis. “Sometimes you think of a poet as very formal and stuffy. And in fact, we discovered that they were funny to the audience at the time. And so there’s a real value to knowing what catalyzed people.”

In that live recording, especially, she pointed out, we are hearing history. “We discovered that John Ashbery, [later New York State poet laureate,] then a young undergraduate, was present” at the Sanders reading. “So when you’re listening to it, you’re also potentially listening to a cough or a laughter or the applause — or just detecting the breath — of the young John Ashbery.”

The recordings’ impact, however, comes from Eliot. To summon the power of a poem being read by its creator, Davis cited the recent case of Amanda Gorman reading “The Hill We Climb” at President Biden’s inauguration. “If they had posted Amanda Gorman’s poem on a screen on the steps of the Capitol, but she had not been present to read it, would it have had the impact?”