Neighborhood revitalization is a key priority for Birmingham, Ala., Mayor Randall Woodfin (left). Woodfin was a member of the second class of Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative.

Credit: Bloomberg Philanthropies

Two mayors talk pandemic, civic unrest, and the value of a network of peers

New $150M Bloomberg Center to boost support for municipal leaders

In the past year, the spotlight has been trained on the nation’s mayors. American towns and cities faced unprecedented challenges brought by the medical, financial, and educational fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, a national reckoning on equity and race, political unrest, and natural disasters connected to climate change.

To offer additional support to municipal leaders, Harvard and Bloomberg Philanthropies have announced a new Bloomberg Center for Cities at Harvard University, made possible by a $150 million investment from Bloomberg Philanthropies, led by former New York City Mayor and philanthropist Michael Bloomberg, M.B.A. ’66. The new effort builds on the work of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, a collaboration between Bloomberg Philanthropies, Harvard Kennedy School, and Harvard Business School, which has been bringing together mayors from across the nation and the world to learn, strengthen skills, share ideas, and create a community of city leaders since 2017.

The new center will be a hub that will draw on expertise and scholarship from across disciplines and all of Harvard’s Schools. It will be led by Director Jorrit de Jong of the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). De Jong and Rawi Abdelal of Harvard Business School (HBS) will continue as the faculty co-chairs of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, which will be part of the new center.

Plans include the creation of resources to help newly elected mayors build teams, custom programming for additional city hall leaders, research on city governance, and City Hall Fellowships for Harvard graduate students. In addition, 10 endowed faculty positions focused on municipal problem-solving will be named for Emma Bloomberg (M.B.A. ’07, M.P.A. ’07), a graduate of both HKS and HBS.

The Gazette recently spoke to Kathy Sheehan, mayor of Albany, N.Y., and Randall Woodfin, mayor of Birmingham, Ala., and asked them to share how their experience at Harvard as part of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative — the connections they made and the continued support from the program — prepared them to face the toughest year of their careers.

Q&A

Kathy Sheehan and Randall Woodfin

GAZETTE: How are things going back home?

SHEEHAN: It certainly is challenging on many fronts, from the personal — people who’ve lost their jobs or are struggling to keep their businesses open — to health concerns, to the desire to move forward with much-needed changes to address structural racism. This is hard work, and I think it’s made harder by the fact that we can’t be in a room together looking at one another, that we can’t be creating those connections and cues that that happen when you’re in a room together as opposed to on Zoom.

WOODFIN: We’ve been in crisis mode for a year from March. And we’ve tried to manage as best we can. I had a pretty bad bout of COVID myself and actually ended up hospitalized. But overall, my team is better [for it]. We’ve learned a lot. I’m glad it’s the fourth quarter of COVID.

Kathy Sheehan, mayor of Albany, N.Y., had to combat conflicting news and misinformation about COVID-19 among residents. She relied on concepts taught at the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative to bring faith leaders and public officials together to determine the best ways to communicate about the seriousness of COVID-19.

Courtesy of the Office Mayor Kathy Sheehan

GAZETTE: You were both in the BHCLI second cohort alongside mayors from cities with populations ranging from 100,000 to 12 million. What was it like to work alongside mayors from across the country and world, with different populations, facing different issues?

WOODFIN: The best way to learn is through difference. I come from a city that has high poverty, that has a 74 percent Black population. It’s the fourth-Blackest city in America. Twenty-two percent of my city are elderly. My city is an outlier. And so I was definitely able to learn from other mayors whose cities are more diverse in race, more diverse in age, who have more diverse industries, a more diverse tax structure. Definitely various mayors and cities’ tax structures are very different.

SHEEHAN: I remember one amazing moment with the mayor of Freetown, Sierra Leone, who was in my class. We were talking about how you build legitimacy around [the vaccine]. She told the story about how they were dealing with an Ebola outbreak, how the doctors were trying to get people to follow these guidelines, to not do what they normally would do in situations when they’re caring for the sick. Eventually, one of the leaders of a nearby town said, “You know, it gets really hot here, and so in the afternoon, in the height of the sun, many people gather under the trees, and they have conversations as they gather to cool off. You need to meet with people under the trees and talk to them about why they need to do this.” And she explained that when they started to have those conversations under the trees, that was when people within the community started to change their behaviors; it was building legitimacy with those elders, those trusted voices in the community. It was those quiet conversations that really helped to change people’s hearts and minds and started to turn the tide on the epidemic. It doesn’t always have to be a big public meeting. It doesn’t have to be us blaring information at people. It’s meeting people where they are, under the trees and building trust — and then having those individuals take that message and spread it through the community. I think about that all the time.

GAZETTE: You referenced some of the ways you needed to be able to respond to the pandemic. Are there elements of the program that suddenly became particularly relevant over the course of the last year?

SHEEHAN: We’ve been through this unprecedented experience, and there was really no playbook to follow. But the [BHCLI experience] really helped provide a center of gravity and keep us tethered, even if that tethering was just helping us to effectively communicate in a world of a lot of unknowns. I found that incredibly helpful. I was able to say, “OK, with all of the issues that are swirling around us, how do I break it down into digestible pieces of information that will be helpful to my residents and businesses in the city of Albany as they try to navigate these uncharted waters?”

We are somewhat “a tale of two cities.” We have affluent areas, and then we have areas with really significant challenges. For example, [COVID] testing wasn’t getting to certain communities in the city of Albany, and it became really important for us to advocate to make that happen. It also become important to reach out to the community partners who could help us to get that message back to those in power to say, “You’re doing thousands of tests every day in the city of Albany, but guess who’s not getting tested? Our residents.” People were driving here from the surrounding suburbs and taking advantage of this mass testing site, and so the vaccines were not getting to people who are really the most vulnerable to this disease. As mayor I didn’t have the power to set up a testing facility [the health department resides in the county], so I had to figure out the more informal channels to help make that happen. The [BHCLI program] helped me think about where I did have a role and really helped me to figure out how, as a mayor, I can use information to determine where we need to focus more efforts and where we need to more effectively communicate.

WOODFIN: I will call it the art of storytelling. The program showed me that we have to frame things so people can connect. Oftentimes as leaders, we only want to talk about facts, about numbers. But it doesn’t work like that. You want to connect with the everyday people you serve. Unfortunately, I’m in a position to tell people that my great-grandmother died from the coronavirus at age 87. I tell people, “I know many of you all in the community have lost a loved one, or you’ve had a loved one hospitalized. I know this is real.” And we can talk about how we still have to hunker down, to socially distance. We still need to get tested and to get the vaccine, because it’s the best way to save lives and to get back to our way of life. Bloomberg-Harvard really homed in on showing how to be a better communicator through storytelling, through connecting with the people. I think it would have been easier to stand in front of our citizens and just give stats and numbers. But that’s not it. It’s about connecting with the people.

Randall Woodfin, mayor of Birmingham, Ala., said he and his team are applying lessons on using data and evidence in governance to address blighted properties.

Credit: Bloomberg Philanthropies

Twenty-twenty was a year like no other. It is one thing to have a global pandemic in isolation. It’s another thing to add on the economic crisis. It is another thing to add on to that civil unrest. There’s no playbook on how to solve one, let alone three at one time. So we were fortunate in two spaces: in my left hand, a continuation of Bloomberg Harvard in engaging us and offering some best practices and tool kits. But nothing was better than that right hand, of being able to text fellow mayors who were going through the same thing. We literally just started bouncing best practices and ideas off each other. Remember, the leadership of the federal government called this a hoax. We didn’t know when help was going to come. It was the mayors who I leaned on from this program. We talked about how to better communicate with citizens about taking this virus seriously, [the need for] face masks, and other ordinances we needed to have in place as mayors because we couldn’t get the help we needed from our governors. We talked about how to come up with our own local funds to support small businesses who only had 10 to 21 days of cash on hand. With the economic crisis, we were left to fend for ourselves. Everybody’s local economy was the same. Remember, the PPP [Paycheck Protection Program] loans didn’t come right away, federal aid and assistance didn’t come right away. We talked to each about civil unrest and how to engage our police and more accountability and responsibility. We didn’t get that from governors, we didn’t get that from the federal government, we got that from each other. Without this program, let’s say there’s a high probability I would have never had that.

GAZETTE: Mayor Sheehan, can you say more about how the program helped with your work in Albany?

SHEEHAN: One of the areas where social justice issues and COVID intersected was around vaccinations. For example, there were lots of concerns about the speed with which the vaccine was being developed, and through the [COVID sessions] we came to realize that there was a lot of rigor around the development of the vaccine — and that we really needed to focus on building trust in the vaccine.

As the rollout of the vaccine started to come into sharper focus, it became very clear to me that I didn’t need to reach back to redlining or the segregation of our schools to talk about structural racism. I was watching before my eyes a vaccine distribution program being set up that was — and still is — structurally racist. [To get the vaccine] requires mobility, broadband access, [command of the] English language, and it requires that you be able to interact with a computer. And the state was measuring how fast the vaccine was getting into people’s arms. But they weren’t measuring the demographic makeup of whose arms [the vaccine] was getting into. Because of the many things that we talked about through the course of the program, I leaned into that. I was much more effectively able to partner with people at the state level and at the county level to influence accountability measures and to ask for data. I kept asking, “When am I going to see vaccinations by ZIP code, not by where the vaccine is happening but by the ZIP codes of the people who are receiving the vaccine?”

[I was also much more effectively able] to work with my community partners. I reached out to a partner in health care, an entity called the Alliance for Better Health. They developed a platform for us so we could preregister people for the vaccine. Then I worked to advocate to get the vaccine to the providers who would use this list. This allowed us to be very focused on public housing, low-income senior housing, and on working with community partners who were signing people up — and are continuing to sign people up — at food pantries libraries, and other places, so that we can ensure that we’re getting the vaccine to people who need it.

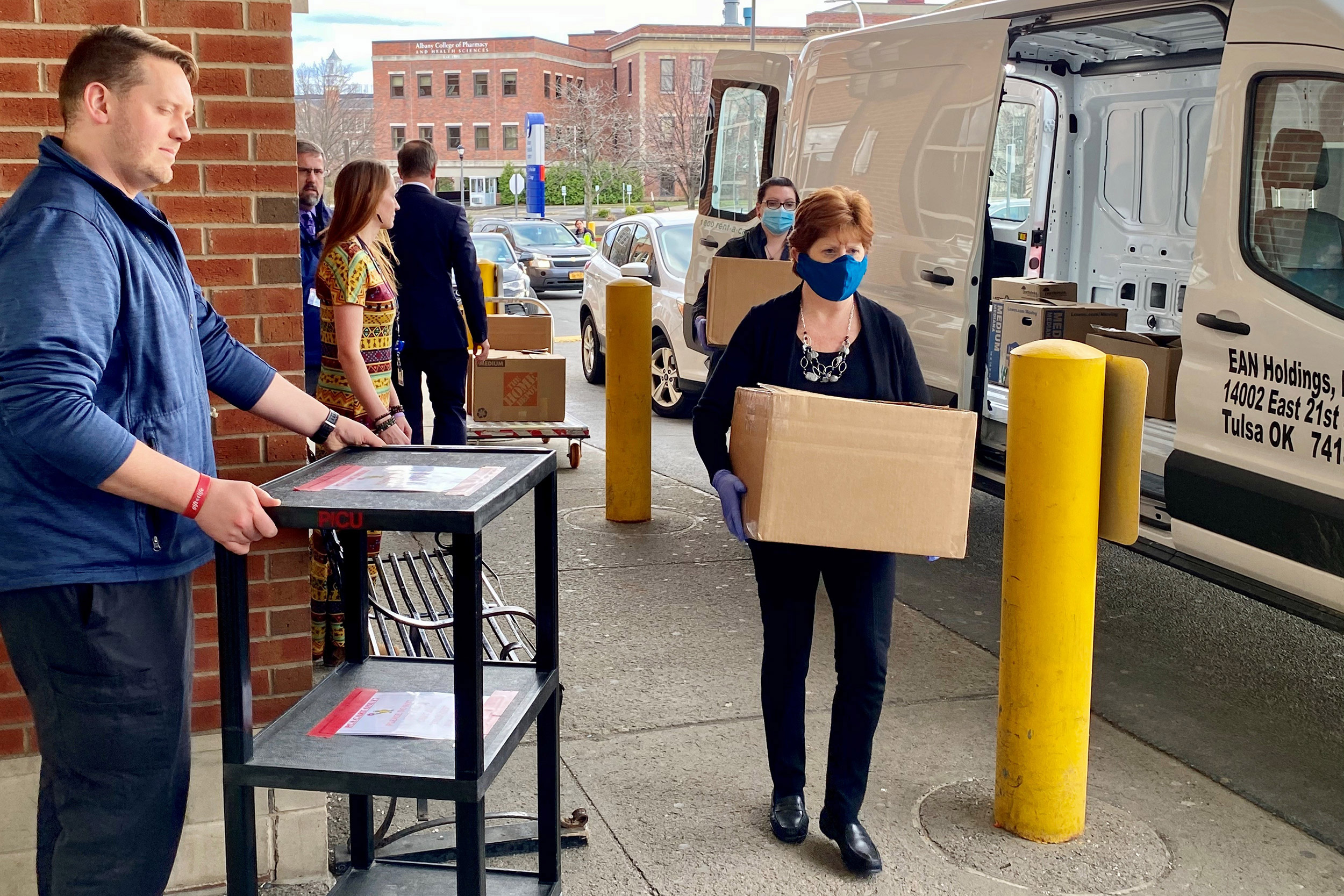

“We’ve been through this unprecedented experience, and there was really no playbook to follow,” said Albany, N.Y., Mayor Kathy Sheehan, who helped distribute food.

Courtesy Office of Mayor Kathy Sheehan

GAZETTE: What do you think you’ll take forward with you — lessons, collaborators, networks, partnerships, or outcomes you think will be meaningful moving forward?

SHEEHAN: I’m sure most of the mayors would say that the most valuable [aspect of the program] is the relationships that you develop with your fellow mayors. It helped us to get through what was a very challenging time and is still a very challenging time. I didn’t feel like I was on an island, especially during the social unrest. It helped me understand that that was going on everywhere.

I truly know and believe that the other mayors are just a phone call away, literally. When there were concerns about violence around Election Day, there were some special sessions that took place, and then when we saw the violence on Jan. 6 — and the threat to capital cities — I was able to reach out to fellow capital city mayors to say, “What are you doing? What’s happening there? How are you preparing?” Actually, that led to us to having the U.S. Conference of Mayors convene the capital city mayors. It started with reaching out to classmates.

WOODFIN: In this position, you can sometimes feel alone, and that can feel burdensome. There’s always something to solve, some fire to put out. You can have a plan all day, but something happens, and you have to veer from that plan. Then, you become part of a Bloomberg-Harvard class, and you participate with mayors across the globe for an entire year. You realize it doesn’t matter if the city’s 100,000 people or 12 million people. It doesn’t matter if your city is majority Black, majority white, or international. We’re all dealing with the same things. And that made me realize three things: I’m not alone, best practices really do exist among us, and there’s always a solution.

Even though all of our local economies are different, all of us had to find a way to not only support the small business owner, [but] to support the hourly worker too, because most of our economies were shut down to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. We literally started benchmarking and creating tailor-made solutions for our city, from what somebody else was doing. That was literally through either picking up the phone or through texting.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.