Activist groups marched demanding climate and racial justice in New York City.

Steve Sanchez/Shutterstock

The fight for environmental justice

Harvard affiliates at the Law School and School of Public Health are working to right the wrongs of decades of discriminatory policy

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. The third chapter, “Environmental Exposure,” explores the experience of people of color with America’s climate policies.

North Carolina is one of the nation’s largest producers of pork. The industry is primarily centered in agricultural portions of Eastern North Carolina, home to a number of Black and Indigenous communities, and a surging Latinx population.

Scattered about the region are thousands of “pig lagoons.” Farms use the open-air pools to store tons of hog waste until it is sprayed over nearby fields to fertilize crops. On windy days, the noxious fumes from the spraying often drift into neighboring areas, many of which are lower income or minority communities, coating homes, cars, and people. The waste has also at times spilled over, tainting water sources.

The coexistence of air pollutants and communities of color isn’t an anomaly, says Hannah Perls, J.D. ’20, but is representative of the environmental injustices that many communities of color across America live with. As a legal fellow at the Environmental & Energy Law Program (EELP) at Harvard Law School, Perls’ work focuses on issues revolving around environmental justice for such communities.

“There’s that great saying – the system isn’t broken; it’s working exactly as it was designed,” she says. “Often environmental justice communities live at the intersection of several inequitable and interlocking systems and ideologies: racism, capitalism, and white supremacy, among others.”

Around the nation, various kinds of facilities that emit dangerous air pollutants tend to be situated in or near communities of color for political and economic reasons. Often, residents of lower-income and minority areas are not consulted in decisions about where, say, factories, oil rigs, or pig lagoons are placed. The communities also tend to lack the financial and political resources to effectively fight the decisions. And public health officials say that the increased exposure to pollutants have had quantifiable negative impacts on the health of residents.

A major contributing factor to that problem is the segregation of residential areas in the nation, owing to racist attitudes and practices, such as redlining. The term finds its roots in federal guidelines established in 1934 that subsidized mortgages in white neighborhoods, but typically not poorer, minority ones, which were delineated in red on maps. Some insurers and lenders adopted similar practices that made it more difficult for home buyers in minority communities to get loans or policies. Redlining was finally made illegal in 1968, but the exclusionary practice left an indelible mark on wealth inequality as it made it more difficult for people of color to buy houses (often a family’s most valuable asset), limited their housing options, and had the effect of packing people of color into segregated communities, where they were sometimes made vulnerable to industrial pollution.

In an episode of the EELP’s “CleanLaw” podcast, Perls dives into the legal strategies that advocates are using to combat systemic inequities and underenforcement of environmental violations in parts of Eastern North Carolina. She speaks with Naeema Muhammad, organizing co-director of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN), and Alexis Andiman, an attorney with Earthjustice, about a civil rights complaint filed with the EPA to address the disparate health impacts for people living near industrial hog farms in the eastern part of the state.

Richard Lazarus, the Howard J. and Katherine W. Aibel Professor of Law, has spent more than three decades trying to solve the environmental disparities faced by communities of color.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“For communities in Eastern North Carolina, and really across the U.S., [federal] policies suppressed the property values of homes built and purchased by Black and immigrant families, thus preventing communities of color from building intergenerational wealth while exposing those same communities to environmental pollution from heavy industry zoned nearby,” Perls said.

The podcast is only one dimension of the program’s broader work in environmental justice. The group also focuses on encouraging participation by members of affected communities, one of the most important paths to environmental justice and one that has been historically neglected. People who have the experiences of living in communities facing environmental disparities are often catalysts for solutions that directly address the impact of the injustices.

“Environmental justice means that you need involvement and participation of peoples of all colors and all income levels in the development, implementation, and enforcement of our protection laws,” says Richard Lazarus, the Howard J. and Katherine W. Aibel Professor of Law. “This is not supposed to be top-down.”

Lazarus, who leads the EELP alongside Jody Freeman, the Archibald Cox Professor of Law, has spent much of the past 30 years of his legal career studying and trying to solve the environmental disparities faced by communities of color, and most recently worked on the Biden administration’s transition team and helped elevate the issue to be a top priority for the president.

He pointed to the administration’s emphasis on diversity at the highest levels of government, particularly in areas that have to do with the environment, as an example of how policymakers across the political spectrum can inclusively work toward environmental justice.

“Michael Regan heading the EPA; Deb Haaland, the first Native American to head the Department of the Interior; Brenda Mallory heading the Council on Environmental Quality … Todd Kim’s nomination to lead the Environment and Natural Resources Division at the Department of Justice … all are expressions of the [government’s] priority on environmental justice.”

The EELP also focuses on evaluating the enforcement and underenforcement of environmental regulations, key reasons that minority communities are disproportionately exposed to pollutants. Although rules and regulations have been implemented by the EPA and other agencies to curb air emissions, water contamination, pesticide use, and other sources of pollution, their enforcement varies widely.

“You have certain communities, which have been overly burdened by violations of air, water, noise, truck traffic, and there’s never been a concerted effort to identify those communities and target them for enforcement,” says Lazarus. “[These] communities were open-season for violations, because there were very few resources for citizen oversight and too little government enforcement.”

Seeing change

One of the most significant symptoms of the climate inequalities that communities of color face is the effect that pollutants have on public health. Researchers at C-CHANGE, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, know that the proximity to highways, railroads, and power plants, and the pollution that comes with it, can be directly linked to some of the most common health issues.

“Black Americans and Hispanic Americans breathe more pollution than white Americans in the United States population, and they are least responsible for its production. It’s a double injustice,” says Aaron Bernstein.

A pediatrician by training, Bernstein leads C-CHANGE, and with his colleagues is on a mission to demonstrate that climate change and solutions for the problem are relevant in people’s lives, and disproportionately so for people of color.

In a 2017 study done at the Chan School, researchers modeled exposure to fossil fuel pollution across Greater Boston and put it against the backdrop of the health of residents in the region. The study found that both Black and Hispanic populations suffered higher exposures to fossil fuel emissions than white populations, with Hispanic people facing as much as 20 percent more emissions. Such high rates of pollution take a drastic toll on health.

“Air pollution causes heart attacks, strokes, lung cancer and is bad for mental health,” notes Bernstein. “Air pollution can harm pregnancies and the health of newborns and infants.”

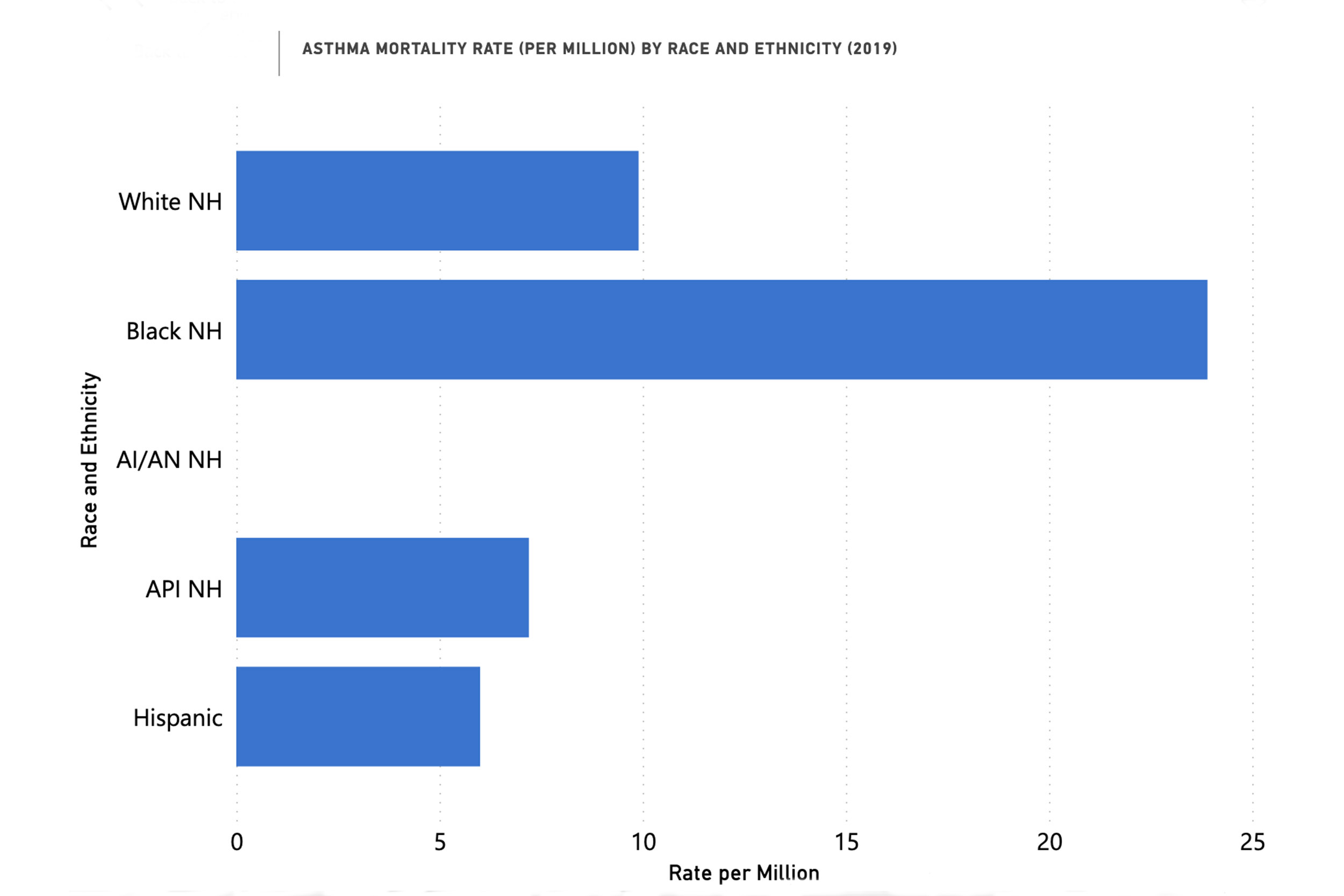

The pollution is particularly detrimental to the respiratory system, leading to an increase in conditions like asthma. Research from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services points out that African Americans were 40 percent more likely to have asthma than white Americans. Data from the Center for Disease Control shows that more than twice as many African Americans die of asthma annually than white Americans, and Black children are five times more likely to be admitted to the hospital for asthma.

“In contrast to other important health arguments about why we need to tackle climate change and stop burning fossil fuels, many of which are somewhat abstract, the case to improve air quality gets personal and urgent,” says Bernstein. “This is about whether your child is going to need to see me in a hospital because they are having a hard time breathing.”

The center’s work focuses on creating a personal dialogue around the impacts of climate change, how it affects people in their everyday lives, and what they can do individually to create positive environmental changes. The Climate Optimist, a monthly newsletter from the program, offers actionable tips for readers on how they can combat climate change. Climate MD, a program co-led by Bernstein and Renee Salas, a Yerby Fellow at the center and practicing emergency medicine physician at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, is focused on educating physicians about why a healthier climate is directly related to a healthier patient.

Salas noted that the national conversation about climate change and climate justice has also collided with America’s reckoning with race. She was hopeful that the dual conversations about racial justice and climate change will yield positive changes.

“We are in a profound moment as a country where we are reflecting on the inequities and disparities from racism in a much more pronounced way,” she said. “However, it is critical that this reflection directly translates into tangible action that gets to the root of the problem. This is especially important for us in the health community, as we need to tackle the health disparities that stem from racism and recognize that these interventions are inherently interconnected with climate solutions.”

In a podcast, Renee Salas discusses how climate change is impacting the everyday health of African American, Latinx, and Indigenous Americans, and why she is hopeful that America is at a turning point. To listen, visit Focus on Harvard.edu.