Author and activist Julia Wright (lower right), filmmaker Malcolm Wright (lower left), and author and Radcliffe Fellow Kiese Laymon (upper left) discuss the novel. The discussion was moderated by Max Rudin.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

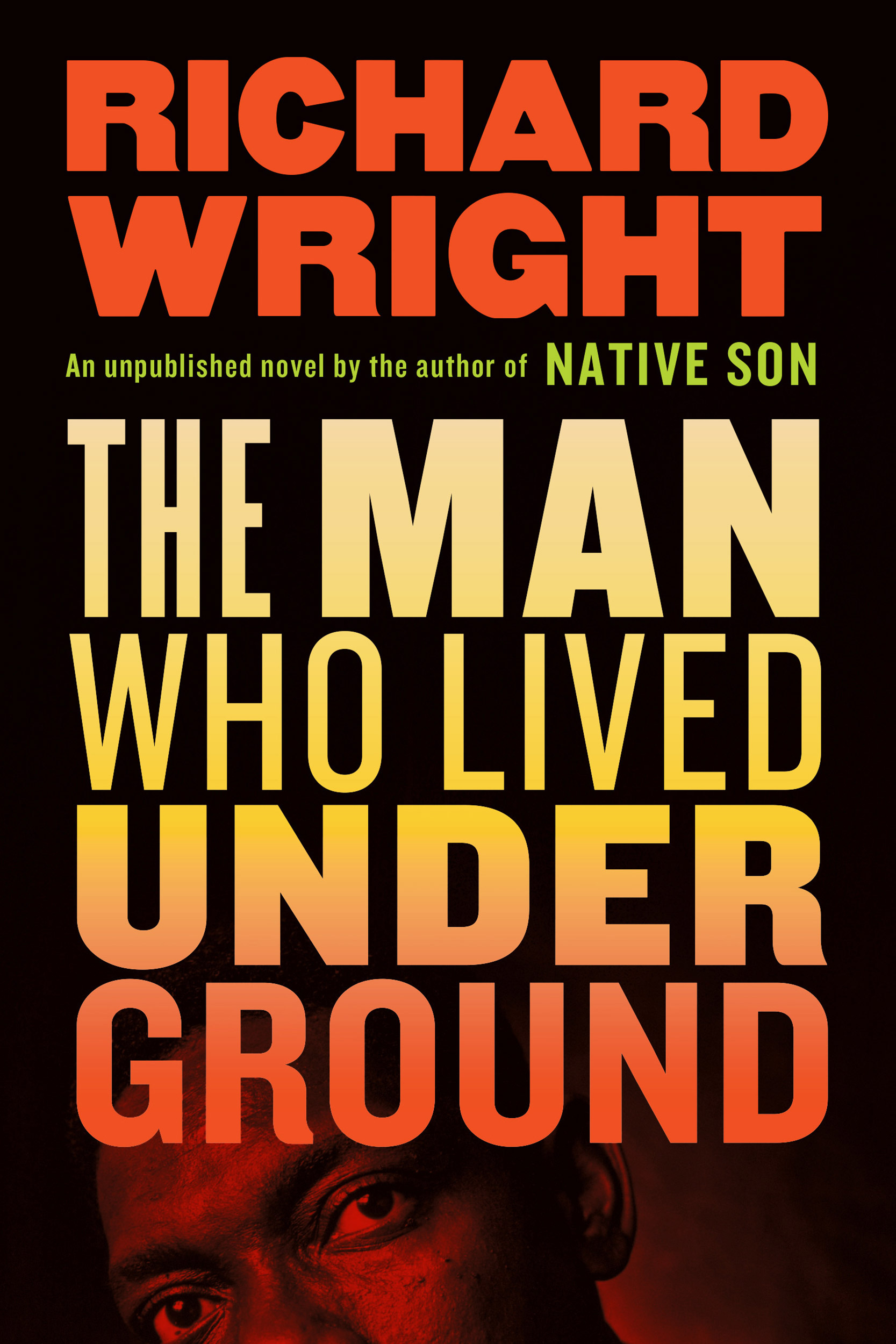

Unearthing ‘The Man Who Lived Underground’

Panel discusses release of a controversial work by Richard Wright, over 60 years after his death

“The Man Who Lived Underground,” an allegorical novel by Richard Wright, will be published for the first time in its entirety on Tuesday, more than 60 years after the death of the influential Black author.

The work, released by the Library of America with the support of Wright’s family, follows Fred Daniels, a Black man who is arrested and coerced into falsely confessing the murder of a white couple. After escaping from the police, Daniels flees to the sewers, where he has an epiphany. Later he emerges to impart his newfound knowledge to others, only to be labeled insane.

The Library of America chose to issue the full text of “The Man Who Lived Underground,” along with Wright’s essay “Memories of My Grandmother” detailing the inspiration behind the book, at the urging of his daughter Julia Wright. The author, journalist, and anti-death-penalty activist first read the complete manuscript more than a decade ago at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, home to Wright’s papers.

“It was like a ton of bricks,” said Julia Wright, recalling that initial encounter during a recent virtual discussion with her son Malcolm (who wrote an afterword for the book) and author and Radcliffe Fellow Kiese Laymon. The event, moderated by Library of America President and Publisher Max Rudin, was presented in partnership with Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

Wright said she found the connections between the current police brutality in the U.S. and the violence that fill her father’s pages “eerie.”

“Are we ready for it yet?,” she wondered aloud about his book. “I don’t know.”

Richard Wright first sent “Underground” to his editor at Harper & Brothers in 1941, a year after the publication of his best-selling novel “Native Son.” The publisher rejected it. Excerpts from the work first appeared in a literary journal in 1942. A portion of the novel later appeared in short story form in an anthology in 1944, but the condensed version left out the author’s first section, the majority of which unfolds in a police station where three white officers beat the innocent Daniels into a false admission of guilt. Many suspect that brutality led publishers to reject the original complete manuscript, but Wright considered it some of his best work, noting in his essay that he had “never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration.”

During the hourlong talk, the panelists drew comparisons between the novel and the author’s own life, and delved into its deeper meanings. Wright’s grandson, filmmaker Malcolm Wright, called the work “prophetic in more than just the continuation of police brutality.” He said that the “extra dimension” that unfolds in the book’s final pages highlights the dangers of turning a blind eye to something as evil as racism. The novel’s denouement, he said, suggests “there’s actually a clock on how long you can ignore something before it bites you in a way that most human beings are incapable of seeing until it’s happened.”

In a departure from the linear narrative of the first section, the novel’s middle chapters take the reader on a surrealist detour into another world as the protagonist seeks shelter in the city’s sewer system. Daniels’ descent into darkness ultimately leads him to a kind of existential enlightenment. Laymon, Flora Hewlett Foundation Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute, called the middle section of Wright’s work “sublime,” noting that the author “was attempting to use his art to experiment about ways to love Black people.”

“One of the things that I see Richard Wright doing in the middle of this book, after Fred Daniels goes underground, is we see the actual character confronting a lot of things that the actual writer was,” Laymon said. “But I don’t want to lose the fact that he is confronting these things in a hope and a desire to love and treat Black people better … [exploring] not just the limits, but the potential of Black love.”

Julia Wright said she sees in those chapters the inspiration for her father’s future work. “To me it is a sort of a reflection on what creativity is. It’s creativity on creativity. It’s a rehearsal for all the creativity that’s going to follow.”

For Malcolm Wright, the book’s middle section represents a kind of emotional and physical exile, something his grandfather would experience in his own life. After a visit to France in 1946, Richard Wright, who had just published his acclaimed memoir “Black Boy,” decided to move his family to Paris. He called it the “psychedelic” kind of experience “you can only have when you make a radical departure from everything you’ve ever known … it’s difficult, but it’s also freeing.”

A passage from the book captures that sentiment: “Outside of time and space he looked down upon the earth and saw that each fleeting day was a day of dying, that men died slowly with each passing moment as much as they did in war, that human grief and sorrow were utterly insufficient to this vast, dreary spectacle.”

A true racial reckoning demands deep soul-searching and difficult conversations in which people face their worst impulses, Malcolm Wright added, something he feels his grandfather was also trying to address with his prose. “I think that’s something really powerful that we can take from the novel, this brave exploration of the darkness.”