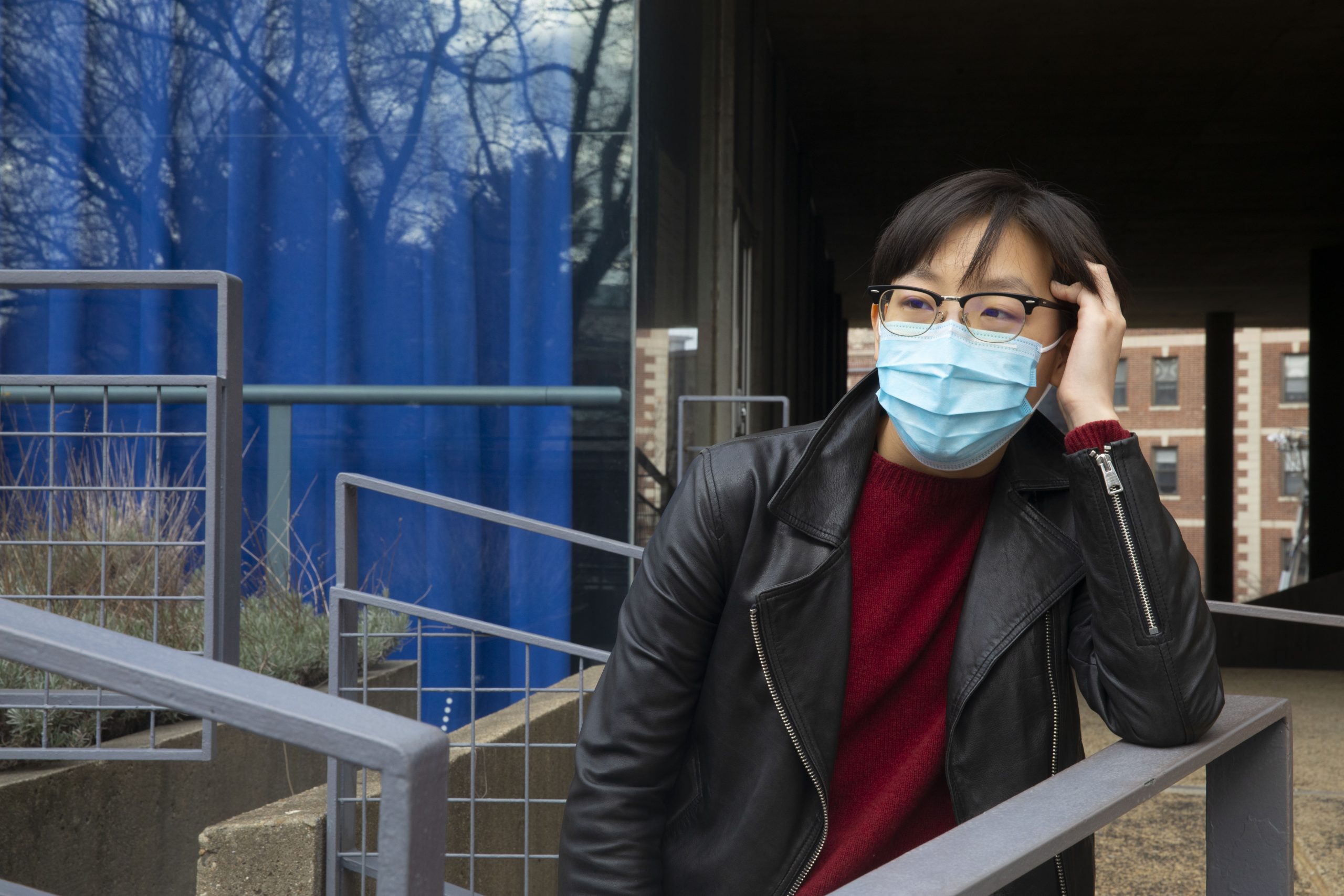

Muhua Yang ’21 will enter the University of Iowa’s master of fine arts program in literary translation this fall.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A literary translator, far from home, feels a tie with an exiled Ovid

Muhua Yang ’21 says poet’s work resonates in an era of global displacement — and COVID

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

In 8 A.D., Emperor Augustus mysteriously banished the poet Ovid from Rome to the shores of the Black Sea in what is now Romania. There he wrote “Tristia” (“Sad Things”), a collection of poems that detailed his experiences of homesickness, separation, and longing, far from his homeland, his friends, and his wife.

More than 2,000 years later, Muhua Yang ’21 — living in Cambridge and separated from friends and family by the pandemic — chose the elegies of the five volumes of “Tristia” as the subject of their senior thesis in literary translation.

“We’re living in an age in which short- and long-term migration, exile, and displacement are becoming increasingly common. We’re also in an age in which technology brings us closer together, but also makes us feel far away from each other and isolated, especially in this pandemic era,” said Yang, a joint concentrator in comparative literature and classics who comes from Beijing.

“Ovid’s poetry speaks to me a great deal, since this deep yearning for home is something that I feel intensely as an international student,” Yang added. “But I don’t think I am alone in finding solace in Ovid’s words, and I believe that the ‘Tristia’ can serve as a balm to us in our alienation in the modern world.”

Growing up in Beijing, Yang was fascinated by the ways literature and film could have bearing on how people lived their lives. The experience of living in the United Kingdom for two years as a child sparked a love of words and a deep appreciation for the role languages play in building connections between seemingly disparate worlds.

“Ovid’s poetry speaks to me a great deal, since this deep yearning for home is something that I feel intensely as an international student.”

Muhua Yang ’21

“Words conjure worlds and bring them into being. For this reason, I have always had a desire to learn more languages,” said Yang. “A lot of the literature I read is grounded in the classical tradition, and part of the reason why I wanted to study classical languages was so that I could tap into the very roots of the languages and stories that I loved.”

They dove headfirst into the classics at Harvard, enrolling in Ancient Greek their first semester. Later, they spent two summers learning Latin at the City University of New York’s Latin/Greek Institute, where they found a community dedicated to learning language.

Back on campus, they found inspiration in the extensive connections between Classics and modern culture. In conversations with Richard Thomas, George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics, Yang learned about the ways Bob Dylan wove Peter Green’s translation of the “Tristia” into his lyrics. In the Art, Film, and Visual Studies Department course “Adventure and Fantasy Simulation, 1871-2036” with John Stilgoe, Robert and Lois Orchard Professor in the History of Landscape, Yang made connections between classical mythology and contemporary fantasy.

Outside the classroom, their cinematic universe expanded through frequent attendance at the Harvard Film Archive and internships at the Brattle Theatre in Harvard Square and the Harvard Library’s Weissman Preservation Center.

“Muhua is part of a new generation of classicists, both in terms of their background and their fairly recent arrival to the field,” said Thomas, who teaches on Dylan and advised Yang’s senior thesis. “They are a testament to what a field like classics can do to the imagination of a young person who has discovered it.”

A pivotal moment in their Harvard journey was when Yang participated in a comparative literature seminar on translation with Sandra Naddaff, senior lecturer and director of undergraduate studies in comparative literature and dean of Harvard Summer School. Drawn to translation initially as a way to improve their Latin skills, they soon developed a passion for translation as an avenue for connecting readers with ideas and stories that they would not have otherwise encountered.

“Translation is a celebration of the differences between languages, and translations continue the life of the original text,” said Yang. “I’m still at the very beginning of my translation journey, but I want to excite my readers and to recreate for them the experience of reading a piece of literature in its original language.”

Yang will enter the University of Iowa’s master of fine arts program in literary translation this fall, joining a small but passionate cohort of translators who see immense value in connecting to other cultures and time periods through literature. An oft-cited statistic reports only about 3 percent of books published in English were originally written in another language. For Yang, this low figure is a motivator, not a deterrent, to continue their work in the field.

At Iowa, they plan to hone their craft in translating Latin literature and engage also in the translation of more contemporary Chinese literature.

“I had an incredible Chinese teacher and mentor in high school, Mr. He Jie, who introduced us to books that I don’t think I would have otherwise encountered,” said Yang. “To this day, I think of the writing of Shi Tiesheng, Lu Xun, and Hai Zi as some of the greatest influences on the way I look at the world and live my life, and I would like to share these works with others.”