Racial wealth gap may be a key to other inequities

Illustration by Gary Waters

A look at how and why we got there and what we can do about it

“Unequal” is a series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at the racial wealth gap in America.

The wealth gap between Black and white Americans has been persistent and extreme. It represents, scholars say, the accumulated effects of four centuries of institutional and systemic racism and bears major responsibility for disparities in income, health, education, and opportunity that continue to this day.

Consider that right now the net wealth of a typical Black family in America is around one-tenth that of a white family. A 2018 analysis of U.S. incomes and wealth written by economists Moritz Kuhn, Moritz Schularick, and Ulrike I. Steins and published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis concluded, “The historical data also reveal that no progress has been made in reducing income and wealth inequalities between black and white households over the past 70 years.”

It’s no surprise. After the end of slavery and the failed Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws, which existed till the late 1960s, virtually ensured that Black Americans in the South would not be able to accumulate or to pass on wealth. And through the Great Migration and after, African Americans faced employment, housing, and educational discrimination across the country. After World War II many white veterans were able to take advantage of programs like the GI Bill to buy homes — the largest asset held by most American families — with low-interest loans, but lenders often unfairly turned down Black applicants, shutting those vets out of the benefit. (As of the end of 2020 the homeownership rate for Black families stood at about 44 percent, compared with 75 percent for white families, according to the Census Bureau.) Redlining — typically the systemic denial of loans or insurance in predominantly minority areas — held down property values and hampered African American families’ ability to live where they chose.

The 2020 pandemic and its economic fallout had a disproportionate toll on people of color, and many expect that it will widen the gap in various areas, including wealth. At Harvard, experts from different disciplines are studying the problem to find its roots and possible ways to level the playing field to ensure all have an equal chance to achieve the American dream. Here we will take a look at a few, several of which focus on education as a long-term path out.

A history older than the nation

Khalil Muhammad, Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race, and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, traces the roots of disparity to the Colonial period, when the European settlement and conquest of North America took place.

The process began in the second half of the 17th century, said Muhammad, when European settlers stripped Natives of their lands and used Africans as enslaved labor, preventing them from fully participating in the economy and reaping the fruits of their work.

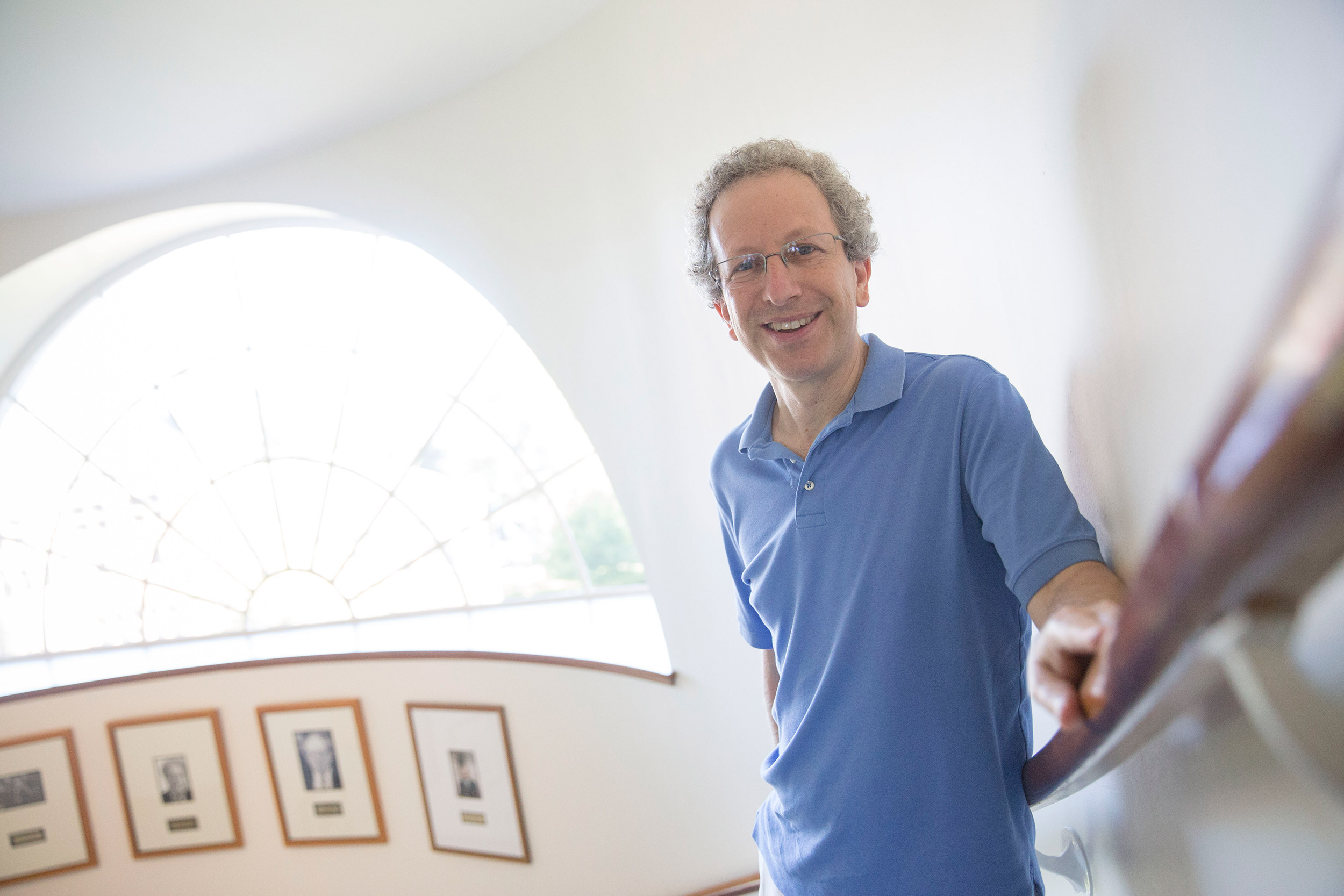

“If we want to undo the cultural infrastructure that is hand in glove with the economic and political racism and domination of people, we have to start very young,” says Khalil Muhammad of the Kennedy School and Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Photo by Martha Stewart

“The two dominant non-European populations, Indigenous and Africans, were subjected to various coercive forms of labor that would be distinct from the experience of indentured European servants,” said Muhammad, who is also the Suzanne Young Murray Professor at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. “And as such, racism became an economic imperative to harness land and labor for the purpose of wealth creation, and that did not change in any substantial way until really about the 1960s.”

In fact the founders discovered that the issues of Black slavery and equality were so divisive that they opted to kick the can down the road, hoping some future generation would prove wiser or better.

With the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a crowning achievement of the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans finally gained full citizenship. Many believed that would end the era of Black inequality, but it did not, said Muhammad, because that thinking failed to account for how deeply systemic the problem had become.

Such misconceptions have tended to make it difficult to gain widespread public support for the implementation of policies to close the disparities between Blacks and whites. That’s why it’s important to institutionalize anti-racist practices and policies in civil society and government, said Muhammad, as well to better enforce anti-discrimination laws and investment in schools in low-income neighborhoods. But he also believes a “massive commitment to anti-bias education” starting in kindergarten is necessary.

“If we want to undo the cultural infrastructure that is hand in glove with the economic and political racism and domination of people, we have to start very young,” said Muhammad. “Anti-bias education is a social vaccine to vaccinate our children against the disease of racism. Imagine what the world would look like in a generation.”

A legacy that benefits some and hurts others

Over the past decades, many scholars have examined the Black-white gap in household wealth. But it was in 1995 that sociologists Thomas Shapiro and Melvin Oliver put wealth inequality on the map with their groundbreaking book, “Black Wealth, White Wealth.” Their research analyzed the role of wealth, or accumulated assets, rather than that of income in the persistent racial divide.

“Wealth is distinctive because it can be used as a cushion, and it can be directly passed down across generations,” providing greater opportunity in the present and the future, says Alexandra Killewald, professor of sociology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Income is unequal, but wealth is even more unequal,” said Alexandra Killewald, professor of sociology in the Faculty of Art and Sciences, who studies inequality in the contemporary U.S.

“You can think of income as water flowing into your bathtub, whereas wealth is like the water that’s sitting in the bathtub,” she said. “If you have wealth, it can protect you if you lose your job or your house. Wealth is distinctive because it can be used as a cushion, and it can be directly passed down across generations,” providing families more choices and greater opportunity in the present and the future.

Most scholars agree that the legacy of slavery and other subsequent forms of legal discrimination against African Americans have hindered their ability to accumulate wealth. “Today’s African American adults and children are living with the legacy of discrimination, inequality, and exclusion, from slavery to redlining and other discriminatory practices,” said Killewald. “And in turn, white Americans are benefiting from legacies of advantage.”

The typical white American family has roughly 10 times as much wealth as the typical African American family and the typical Latino family. In other words, while the median white household has about $100,000-$200,000 net worth, Blacks and Latinos have $10,000-$20,000 net worth. Depending on the year or how it’s measured, those numbers may change, as shown by a report by the Pew Research Center, but the wealth racial gap has continued for decades. “It’s a staggeringly large number,” said Killewald.

The divide persists across generations, said Killewald, who researched the subject with co-author Fabian Pfeffer of the University of Michigan in an article that included striking visualizations. One of them shows that Black parents tend to have much lower wealth than white parents, and that Black and white children tend to follow the wealth position of their parents, reproducing inequality across generations. The study concludes that “today’s black-white gaps in wealth arise from both the historical disadvantage reflected in the unequal starting position of black and white children and contemporary processes, including continued institutionalized discrimination.”

How inequality affects education

Many scholars consider education to be the key to narrowing the gap, and economist Richard Murnane is one of them.

During the last 40 years, Murnane examined the interactions between the U.S. economy and its educational system and the ways in which it has affected the educational opportunities of low-income children, who are disproportionately Black or Latinx.

“The extraordinary income inequality in the United States diminishes opportunities for low-income families and for children of color,” said Murnane, Juliana W. and William Foss Thompson Research Professor of Education and Society at the Graduate School of Education.

Rising inequality has led to growing gaps in educational resources and learning opportunities between high-income families and their low-income counterparts, as well as residential and educational segregation by income. As a result, inequality poses a danger to the promise that U.S. public education provides children with an equal chance at a better life than their parents.

Unequal distribution of economic growth has played a major role in why children who earn more than their parents has declined sharply in America over the past half century, says Raj Chetty, a professor of economics and co-author of the study “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

“One statement that most everybody across the political spectrum agrees with is that if a child grows up poor, but works hard and takes advantage of opportunities, that child’s children will have a better life,” said Murnane. “That’s less true now.”

A study on the “fading American dream” co-authored by Raj Chetty, William A. Ackman Professor of Economics, and others concluded that “absolute mobility — the fraction of children who earn more than their parents — has declined sharply in America over the past half century primarily because of the growth in inequality.”

Economic mobility rates are lower in the U.S. than in some European countries, and the American dream seems to grow more unreachable as inequality grows. Murnane warns that the government must address the problem as large sectors of the American population sink into despair and frustration.

“A great many people, especially males, have grown up thinking they would take care of their families, and the inability to do that has left them angry, frustrated, and depressed,” said Murnane. “That was what they grew up expecting, and that has not been possible for them. That’s a deep challenge to how people feel about themselves. And that’s a fundamental problem.”

The American dream: Out of reach

Economists Claudia Goldin, Henry Lee Professor of Economics, and Lawrence Katz, Elizabeth Allison Professor of Economics, believe that the solution to reducing income inequality, which is strongly tied to the wealth gap, is to close the educational divide.

Goldin and Katz examined wages and income inequality in the U.S. from the end of the 19th century to the early 21st century in their trailblazing book “The Race Between Education and Technology.”

What they found was that in periods where there was improved access to education amid technological change, as in the early 1900s when public high schools sprouted across the nation amid the Industrial Age, workers’ earnings rose. Inequality began to grow in the 1980s as the economy started to shift toward knowledge-based industries and the supply of highly trained workers fell below demand.

Expanding access to higher education could actually help reduce inequality, say economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz.

File photos by Rose Lincoln and Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographers

Around that time, the rates of college graduation began to decrease and overall high school graduation numbers leveled off. For Goldin and Katz, expanding access to higher education could actually help reduce inequality.

“You could wipe out a large fraction of inequality by ramping up the education of individuals who are limited in their ability to access and finish a college education,” said Goldin.

The problem of wealth inequality is more extreme than income inequality since the former builds on the latter, said Katz, and their effects persists across generations. The legacies of the Jim Crow era and racism against Blacks are expressed today in residential segregation, housing discrimination, and discrimination in the labor market.

For Katz, who has been studying housing discrimination and its effects on upward mobility, public policies can be implemented to reduce residential segregation. A study Katz co-authored with Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, professor of economics, found that when low-income families move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, with help of housing vouchers and assistance, it is “likely to reduce the persistence of poverty across generations.” Chetty and Hendren, along with John Friedman of Brown University, were the co-founding directors of the Equality of Opportunity Project, now expanded and called Opportunity Insights, based at Harvard.

Growing inequality is spoiling the chances to have a better life than the previous generation. Recent numbers show that the top 1 percent has seen their wages grow by 157 percent over the last four decades, while the wages of the bottom 90 percent grew by only 24 percent.

Inequality is one of the factors keeping the American dream out of reach, said Goldin.

“The American dream has sort of shifted from one in which the economic growth of the nation was shared more across the income distribution, where the growth rate of the income of those at the bottom quartile was about the same, if not more, than the growth at the top quartile,” said Goldin. “And today it’s not that way at all: the bottom quartile isn’t going anywhere and the top is going rapidly up.”

To keep the American dream alive and return to the era of shared prosperity, the government must act, said Katz. Both Goldin and Katz believe that an expansion of investment in higher education infrastructure and access to a high-quality college education would have a powerful impact in the lives of many Americans. It could be similar to the effects of the high school movement, which lifted millions of American families out of poverty during the first half of the 20th century.

“In the early 20th century, we allowed everyone access to high school,” said Katz. “We have never done that for college, even though college is as essential today as high school was 100 years ago.”

Additional benefits of higher education

The economic returns of a college degree are important, but the social returns are also valuable, said Anthony Jack, assistant professor of education at the Graduate School of Education.

“Workers who are more educated tend to be in jobs that are more recession- and pandemic- proof,” said Jack, who also holds the Shutzer Assistant Professorships at the Radcliffe Institute. “They also tend to live longer, have better health outcomes, and be more civically engaged. Education means more than just extra dollars in the bank. It’s also the constellation of things that come along with it.”

But the road to college has become increasingly harder, especially for low-income people, even though access to college for disadvantaged students has increased over the past two decades. A report by the Pew Research Center found that the number of enrolled undergraduates from lower-income backgrounds grew from 12 percent in 1996 to 20 percent in 2016. Most of that growth has taken place in public two-year colleges and less-selective institutions.

“Education may be the great equalizer, but access to an equal education has never been part of the American story,” says Anthony Jack, assistant professor of education at the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Selective universities have also opened their gates to poor students, however. In 1998, Princeton became the first Ivy League university to offer full financial aid to low-income students, and others followed suit. At Harvard, 55 percent of undergraduates receive need-based scholarships, and the 20 percent of Harvard parents who have total incomes below $65,000 don’t pay anything at all.

Still, access to college “varies greatly by parent income,” according to a study by Opportunity Insights. Children with parents in the top 1 percent are 77 times more likely to attend elite colleges and universities than children with parents in the bottom 20 percent.

To Jack, those numbers showcase that access to college is highly unequal and is influenced by income, race, wealth, and ZIP code. “Education may be the great equalizer, but access to an equal education has never been part of the American story,” he said. “Higher education is highly stratified. The wealthier the family, the higher the likelihood that students will enter a selective college. The inequality doesn’t end there. What happens if you are one of the few low-income students who make it into these elite schools?”

For Jack, that is not a rhetorical question. The middle son of a single mother who worked as a school security guard, Jack rose from a working-class neighborhood in Coconut Grove, Fla., to attend Amherst College, with the help of financial aid. He then came to Harvard, where he graduated with a doctorate in sociology in 2016. Two years later, Jack wrote the book “The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges are Failing Disadvantaged Students” about what it’s like to be a low-income student in selective universities, partly inspired by his own life.

Elite universities have made progress in recruiting more low-income students to their campuses, but there is much more work to be done to ensure that those students use their four years there as a springboard to a better future the same way their richer counterparts do, said Jack.

“The real question is not only how to increase access to colleges and universities,” said Jack. “We must pay attention to what happens once those low-income students move into campus, because that’s where inequality gets reproduced in ways that are sometimes invisible but no less insidious.”

A Marshall Plan for higher education

So if greater access to public higher education would help close the wealth gap, what we need is a kind of Marshall Plan to fix the system, says economist David J. Deming, professor of public policy and director of the Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School.

That U.S. government initiative helped rebuild infrastructure and economy in Europe after the destruction of World War II. Deming’s ambitious proposal would likewise focus resources on overhauling and expanding the size and number of two- and four-year public institutions, with a goal of making access to college virtually universal.

“We ought to set a goal of increasing access to higher education for low-income students and students of color, to basically equalize education opportunity,” said Deming. “We need to invest in public higher education because it actually would make a difference in terms of intergenerational mobility.”

For one, public higher education is where most of the nation’s post-secondary schooling takes place. A report by the National Center for Education Statistics found that of the 19.7 million college students enrolled in the fall of 2019, 14.5 million attended public colleges and universities compared with 5.1 million enrolled in private institutions.

David J. Deming’s vision involves far-reaching investment across two-year colleges and four-year universities.

Kris Snibbw/Harvard file photo

The number of students enrolled in post-secondary education has skyrocketed over the past five decades. The report predicted that by the fall of 2029, more than 20 million students will be enrolled in college. Of them, nearly 15 million will attend public institutions.

Deming’s vision would involve far-reaching investment across two-year colleges and four-year universities, many of which have been historically underfunded and understaffed. Instructors are often adjunct faculty who teach large classes and have high course loads, and many institutions lack tutoring and counseling services to help less-prepared students navigate through college.

In terms of investment per student, the scale of inequality in resources is much greater in higher education than it is at the K-12 level. As an example, Deming points out that a rich school district might spend 20 percent more per student than a poor school district, whereas Harvard spends more than $100,000 per year per student, and Bunker Hill Community College spends about $10,000 or $15,000 per year per student.

“Just purely in terms of dollars and cents, the disparity is much, much greater at the higher education level,” said Deming.

Investing in higher public education won’t solve all the myriad problems that affect inequality, such as the declining minimum wage and discrimination in the labor market, among others. But it would be a big first step, he said.