A 231-million-year-old skull belongs to a previously unknown species of lizard-like reptile.

Credit: Ricardo Martinez

Knowing a big deal when you see it

Analysis of fossil by Harvard researcher’s team sheds light on reptile evolution

It’s not uncommon for scientists to have to run experiments numerous times to see whether they have a big discovery on their hands. Every once in a while, though, a researcher makes a big find more or less by eyeballing it. That’s essentially what Tiago R. Simões did when he saw pictures of a 231-million-year-old reptile skull, originally found about two decades ago.

“I knew right away because of its age, locality, and some of its anatomical aspects that it was extremely important,” said Simões, a researcher in the lab of Harvard paleontologist Stephanie Pierce. “I knew we needed to give this priority and get the CT scan data to see exactly what we have.”

“We have very few fossils from 240 or 250 million years ago … and the very few fossils that we have are extremely fragmented,” explained Tiago R. Simões.

Courtesy of Tiago R. Simões

His suspicion was right. Analysis of the scans after the project got going last summer showed the fossil belonged to a previously unknown species of lizard-like reptile, representing the earliest evolving member of a lineage that today includes all lizards, snakes, and their closest relatives. That’s nearly 11,000 species altogether.

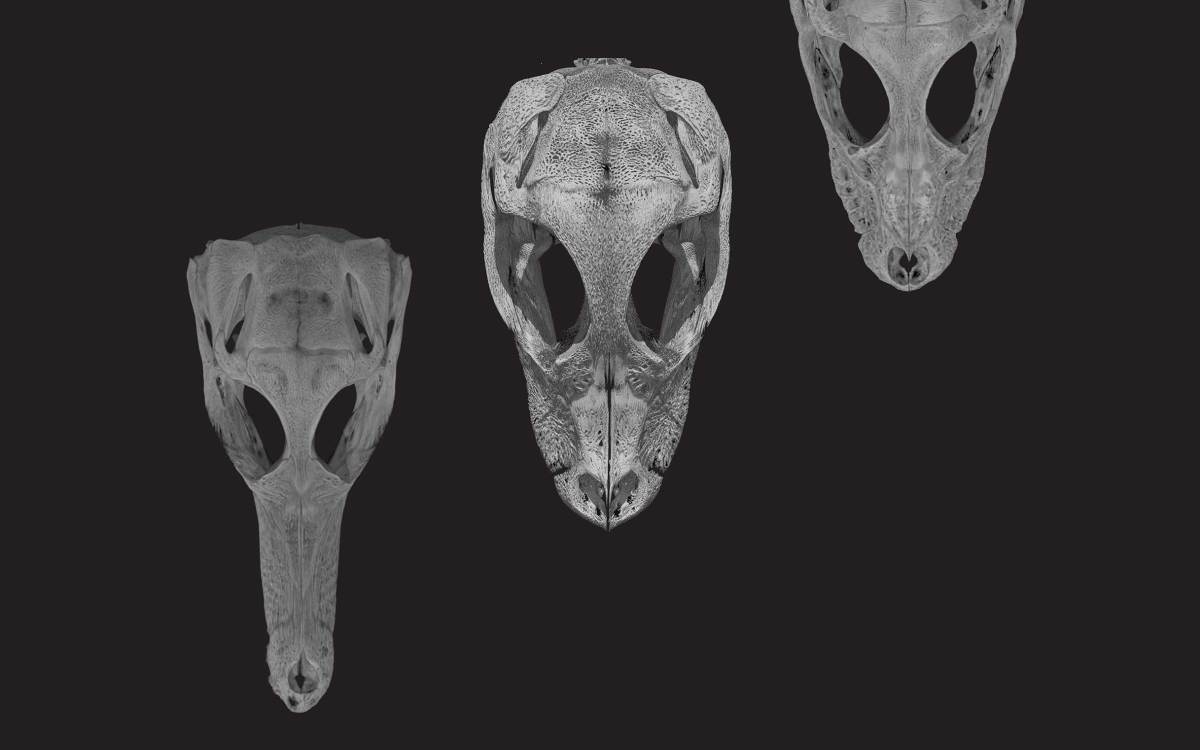

Unearthed in the moonlike desert landscape of Ischigualasto Provincial Park in northwest Argentina, the fossil is of a lepidosaur, one of the major evolutionary branches of reptiles. It is the first three-dimensionally intact skull of a primitive member of this lineage ever found, and its discovery can help researchers better understand the early evolutionary history of this vast group.

“We have very few fossils from 240 or 250 million years ago, when this entire group is expected to have originated, and the very few fossils that we have are extremely fragmented. You have only pieces of jaws and teeth here and there,” said Simões, who is a fellow at Harvard and funded by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. “The first thing that this provides is this missing piece of the puzzle, which is an amazingly well-preserved skull of a primitive member of this lineage that lived in Argentina.”

Results of his analysis were published Wednesday in the journal Nature. The study was a collaboration between Simões and scientists from Argentina and Germany.

Understanding the significance of this find requires a little background. There are two main branches of reptile: archosaurs and lepidosaurs. Archosaurs include all crocodile and dinosaur lineages, while lepidosaurs include squamates (lizards, snakes) and sphenodontians, which have only one living species today, the tuatara of New Zealand.

A Taytalura, thought to be the earliest evolving lepidosaur, which includes lizards and snakes.

Illustration by Jorge Blanco

The lepidosaur fossil was not just any lepidosaur, but the first member of this group that evolved away from the others. That puts it at the top of that lineage and provides key evidence of how lizards first evolved from more primitive reptiles. That kind of respect is shown in the name the scientists chose for it: Taytalura alcoberi, meaning father of the lizards in the Quechua and Kakán languages of the native Andean people of Argentina.

Taytalura is the earliest evolving lepidosaur, but it is not the oldest lepidosaur fossil ever found. That honor belongs to a 242 million-year-old squamate and a 234 million-year-old sphenodontian. That suggests an older Taytalura fossil may one day be found.

Regardless, the age discrepancy shows that these very early lepidosaurs lived side by side with squamates and sphenodontians, known as “true” lepidosaurs, for at least 10 million years during the Triassic period, a fact that was previously unknown.

The researchers used micro-CT scans of the three-dimensionally preserved head to analyze the fossil. It allowed them to compare this early lepidosaurian skull with later lepidosaur and other reptiles. The researchers, for instance, noticed that the skull of the first lepidosaurs looked substantially more like those of sphenodontians than squamates and that squamates represent a major deviation from the older skull patterns. They also found Taytalura teeth differed from those in any living or extinct group of lepidosaurs.

Another surprising finding involved where the fossil was discovered. Till now, almost all fossils of Triassic lepidosaurs have been found in Europe. This is the first early lepidosaur found in South America. It suggests lepidosaurs were able to migrate across the planet (which then was all still one supercontinent) very early in their evolutionary history.

That type of mileage is impressive for such a small creature. While it’s impossible to accurately estimate the total body length of this lizard-like reptile, the one-inch head suggests it likely could fit in the palm of a human hand. The creature most likely fed on insects from desert environments that it shared with some of the oldest dinosaurs in the planet, said Simões. “[It] was most likely preyed upon by some of the first dinosaurs to walk on Earth,” he said.

The researchers hope to explore older rocks in Argentina or other parts of South America and find older members of this lineage. The hope is to determine the exact time when the entire group originated, which will be critical in understanding the long evolutionary history of reptiles to help those that exist today.

“Lepidosaurs survived across three out of the five big mass extinctions on Earth’s history during the last 260 million years,” Simões said. “By accurately reconstructing the long evolutionary history of lepidosaurs, we may be able to tell in much greater detail how they successfully survived and flourished across major environmental shifts in Earth’s past and how they may be impacted by modern human-induced climate change.”