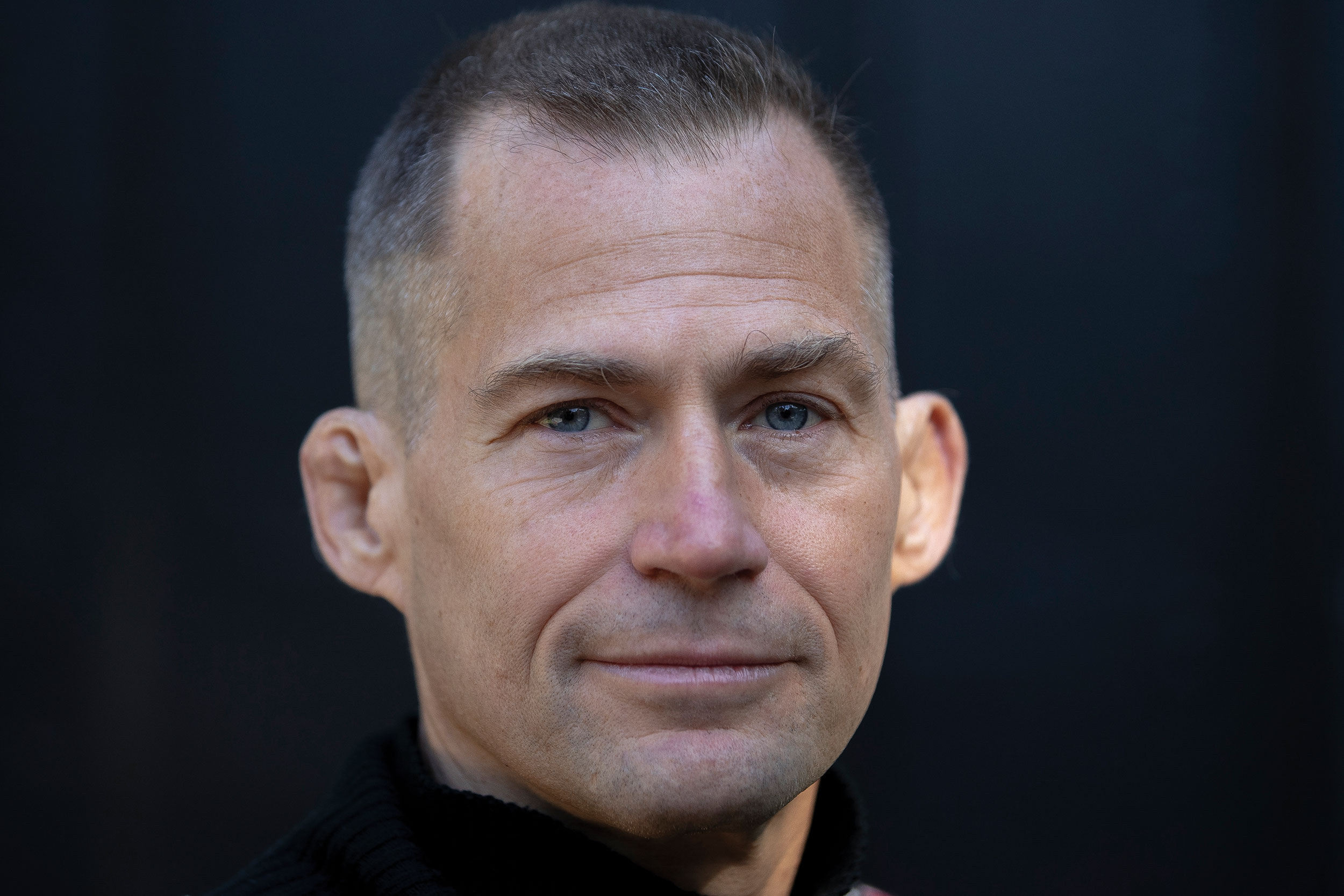

Atticus Lish ’04 is the author of “The War for Gloria.”

Photo by Ryan Hermens

A son nearing adulthood, his mom nearing death

Corey’s estranged father moves in to help care for ALS-stricken Gloria in Atticus Lish’s new novel

Excerpted from “The War for Gloria” by Atticus Lish ’04 published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

You never think about nerves and breathing. You take breathing for granted. You take the nerves under your skin or under the skin of another animal for granted.

His mother loved him. Gloria said, “You make me laugh.” He had a sense of humor about their lives, apparently. She was a single mother and he helped her collect her library off the streets of Boston and never complained about it. They went through crates of books together and shared what they found. Her boy was never bored, even living in her car.

She came from Springfield, which she called her shitty little city. She had come to Boston to go to college. She wanted to stand on the shoulders of Germaine Greer, author of “Sex and Destiny.” She gave birth to Corey at Mass General during what should have been her final year of college.

She crashed in Cleveland Circle, Jamaica Plain, Mission Hill — just her and her son — and her ever-changing roommates. For a time, they stayed at a triple-decker house in Dorchester and he went to a school where a good half the other kids were from the Cape Verde islands. Corey showed his mom the islands on the map, Boa Vista and Santiago off the coast of Senegal, telling her that he’d be sailing here someday when he grew up and went to sea.

He had learned about the concept of a vessel from living in his mother’s car. He had fastened on the concept early. Maybe it was always in his head, one of the basic concepts he was born with — woman, earth, sun, boat.

Her full name was Gloria Goltz. In his mind, she was always a bright blonde. He saw her as having a glass jaw that she kept putting up and it kept getting cracked. But when it came to him, she was stalwart. Once, she took him to a KFC and the manager didn’t want to give her another biscuit with her order, but she demanded it because Corey loved biscuits — he had read that sailors ate hard-tack and salt pork — and the manager, with his thin arms and striped shirt, relented.

“Mom, you’re always giving me things.”

“You never ask for anything.”

Gloria and Corey cut the biscuits on their brown plastic tray and had them with butter and honey.

“Will you mind it when I become a sailor?”

“Oh no. But I want you to be a smart sailor. I don’t want you to be dumb.”

“But will you mind it when I have to leave home?”

“I’ll have to accept it.”

“I’ll come back and visit. Voyages usually take about three years. Whaling voyages can take seven.”

There was a pattern between them of her getting blue and of him helping her. She got blue because of herself. She had not fulfilled the ambition she’d had at seventeen, smoking a cigarette in front of her concrete dorm building at Lesley College in the shadow of Harvard — in the literal shadow of its tombstone-shaped ivy-covered law library — to think and write and shock the world, to condemn it, to synthesize all the available evidence — art, history, movies, negative images and messages in the media, her upbringing, her body in the mirror, her own thoughts, even the smallest things down to the cigarette in her mouth — into a single scream of rage against the patriarchy.

Instead she’d been a waitress, a barmaid taking bottles off a counter after the bar was closed and the band was unplugging its amps and it was too late to do anything but sleep the next day away. And this had gone on for years — years of telling herself that she was finding her voice, that she was getting ready — years of reading not writing, of groggy afternoons, a feminist book in her hands on the T, “Sex and Destiny,” Doc Martens on her feet, reading at the Au Bon Pain, jumping up from her wire chair and standing on the red leather toes of her boots to hug the street musicians who drifted in with the pigeons, carrying guitars, wearing bowler hats and German army trench coats, the wet stink of the bathroom around the corner and the weird men playing chess all day; the hoboes from Seattle, skinheads in suspenders saluting in the street, a dyed Mohawk the size of a circular saw blade from a lumber mill atop a gaunt bald head, kids from the wealthy towns of Concord and Lexington exploring new identities as bitter waifs, at night a wolf pack of multiracial youths from Dorchester there to sell drugs. Her skinny legs. She had dropped out of school. She had hung out in The Pit at Harvard Square, sitting cross-legged in striped tights on the granite wall, her eyes mascaraed, her mouth painted black, debating with her fellow anarchists, giving the finger to the square — the bank, the bricks, the Coop, the clock, the privilege and hypocrisy. The scream of rage was at herself.

So sometimes as the years passed, she’d look at herself and the weight of the time and the evidence of who she was would hit her and she’d get high and ask, “Will it ever be okay?” And for some reason her son would tell her, “Hey, Mom, don’t be sad. You’re great. You’re greater than you know.”

Gloria didn’t just gather things; she left them behind too. She couldn’t keep things as they moved. They lost his toys, his clothes. She cared more than he did, because of the stupid money. She did a self- portrait when she was painting and left it in a closet in Jamaica Plain. Poems too. On the white wall of a room in a house that someone else was renting, she had written in paint “Forgive. This Is the Unimpeachable Voice of God. Let Your Seeing and Your Listening Come from Total Self.” She had lost and gained. An exchange with the city. A coming and a going. The word was many — jobs, roommates, beds, ideas — so many it took a historian to remember. Each year was a miniature history enforcing nonattachment and surprise. Her obsessions and searches for solutions lasted a while and burned out, and they were legion too. And then she returned to them like she might return to a used record store in Allston. She might write a song or pick up paints again, and the feeling she would temporarily have would make her think she never should have dropped this, that doing so had been her worst mistake; here was the answer after all.

As her son grew, he began developing a sharp boyish face. To her, it evoked a primitive axe-head, chipped from flint by, say, the Algonquin Indians. He had a small, round, aerodynamic cranium, like a cheetah. The front of his face — his nose, maxilla, sinuses, jaw — projected forward like a canine skull — what an anthropologist would call prognathous. His blond hair grew in a short, tight cap on his head, like Julius Caesar or Eminem. And he had freckles.

Here was her poem, she thought. How had she forgotten?

The man who was supposed to be Corey’s father was a security officer at MIT. Everything had been stacked against him from the start, said Gloria, who was his biggest champion. He had grown up above a gumball factory in East Boston and all his brothers died. But the most interesting thing about him was that while working as a campus cop, Leonard also studied physics at MIT.

She was already a thin woman, as if she had already had the fundamental things taken away from her, like food or love when she’d needed it. But that was how she chose to eat; she was vegan. She gave the usual double-headed reason: It was healthier for her/better for the planet. Cattle ranching destroys the forests, pollutes the rivers, adds to the greenhouse effect. Her cool blue world of wind, air, forest was in retreat from the hot red screaming dying blood-reeking slaughter world.

Was she afraid of her father’s anger or his body? Or was it her hatred of her own blood and meat that was at the heart of it — that drop of blood on the bathroom floor? Or it could have been genetic. She was flat-chested and narrow-shouldered, built for yoga.

Yoga, she knew, was an Indo-European word that meant “to yoke” — to yoke the body and the spirit together by means of the breath. The breath contained the energy called prana. The prana circulated through the body like an ocean current. The circling of the prana-current made the body healthy, just as the circling of the ocean currents made the planet healthy. If you stopped the tide, the earth would die.

The circulation was like the blood but was not the blood. The energy flowed through silver meridians and a sun that was not the sun glowed in the sacral plexus. It was a moon. To her sacral meant “sacred,” the sacred female moon.

Eggs were okay to eat as long as they were harvested humanely. These were some of her beliefs as she approached the end of her life.

Copyright © 2021 by Atticus Lish.