Sailing alone, under the stars, and fast

Chan School’s Hammitt wins Bermuda sailing race

Jim Hammitt at the start of the singlehanded leg of the Bermuda One-Two Yacht Race in dense fog off Newport, RI.

Photo by Susie Klein

Jim Hammitt knows well the two rules of offshore sailboat racing: First, it doesn’t matter how fast you go as long as you’re headed in the right direction; and second, it doesn’t matter what direction you go, as long as you sail fast.

Hammitt managed to thread the needle on those conflicting priorities in June, sailing fast and in the right direction over 10 days at sea — five of them alone — to win the 2021 Bermuda One-Two, a 1,270-mile, there-and-back race between Newport, Rhode Island, and St. George’s, Bermuda. The race gets its “One-Two” moniker from the number of people aboard each leg, meaning he sailed its first 635 miles entirely alone.

Hammitt is professor of economics and decision sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a former captain of the Harvard College Sailing Team. He managed to place first on the initial leg despite sleeping just 15 to 20 minutes at a time. The chain of catnaps allowed him to keep a more or less constant watch on the wind, sails, seas, and a hazard little appreciated by landlubbers: boat traffic.

Friends of Hammitt, several of whom are fellow lifelong sailors, describe his initial five-day solo slog as “brutal,” but Hammitt was more sanguine, saying that though there were stretches where he had to stay awake for several hours, there were also many stretches when the check on sails and conditions took just minutes, allowing him to settle right back in for another snooze.

Jim Hammitt at the helm of Reveille leaving Bermuda after the start of the doublehanded leg of the Bermuda One-Two Yacht Race.

Photo by John Paulling

“I was kind of tired when I got there, but it was enough. It wasn’t like I was at the end of my rope,” Hammitt said.

That he got there at all is actually a tale of plans altered and twisted — as so many are these days — by COVID-19.

In 2018, Hammitt’s wife, Susie Klein — an avid sailor and former racer herself — suggested that he enter their boat, a 36-year-old, 41-foot sloop named Reveille, in one of the oldest and most prestigious East Coast races, the biennial Newport Bermuda Race. She suggested he enter in the double-handed division and race with an old friend, John Paulling. Hammitt agreed, and with an eye on the 2020 starting line, the couple began making the safety and modernization upgrades to the Reveille that were required before embarking on a voyage almost entirely out of sight of land.

When the pandemic struck, the Newport Bermuda Race was an early casualty. Its cancellation sent a wave of disappointment through its 200 entrants, including Hammitt, who began looking for another opportunity. The Bermuda One-Two is much smaller — fewer than 30 boats entered — and it had the advantage of not only involving fewer participants, but also running a year later, in June 2021, during a vaccine-fueled spurt of pandemic optimism before the delta variant darkened the COVID outlook again.

Hammitt, co-director of the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, said the race was his first attempt at competing solo. He’d long admired feats of singlehanded sailors like fellow Harvard alum Richard Wilson, who had twice sailed a grueling, singlehanded circumnavigation called the Vendée Globe. But Hammitt said he was put off by the danger lone sailors face because of their inability to keep a lookout while asleep. In recent years, however, the development and widespread adoption of the Automatic Identification System, which automatically broadcasts a boat’s position and speed to surrounding vessels, lessened the risk and made him willing to take on the challenge.

Race day, June 4, dawned “pea soup” foggy off Newport. Hammitt, alone on the Reveille, found the starting line and stuck nearby, afraid he’d lose it in the fog. After the start, he headed south in winds that would remain relatively steady, between about 15 and 30 mph, for the next 400 miles. Hammitt said those early winds allowed him to sail fast without being overpowered, which would have forced him to tackle the cumbersome task of changing the large jib called the genoa to a smaller jib that would make the boat easier to control, but possibly at the expense of speed. When the wind picked up more than he was comfortable with, he was able to reduce sail by reefing the main.

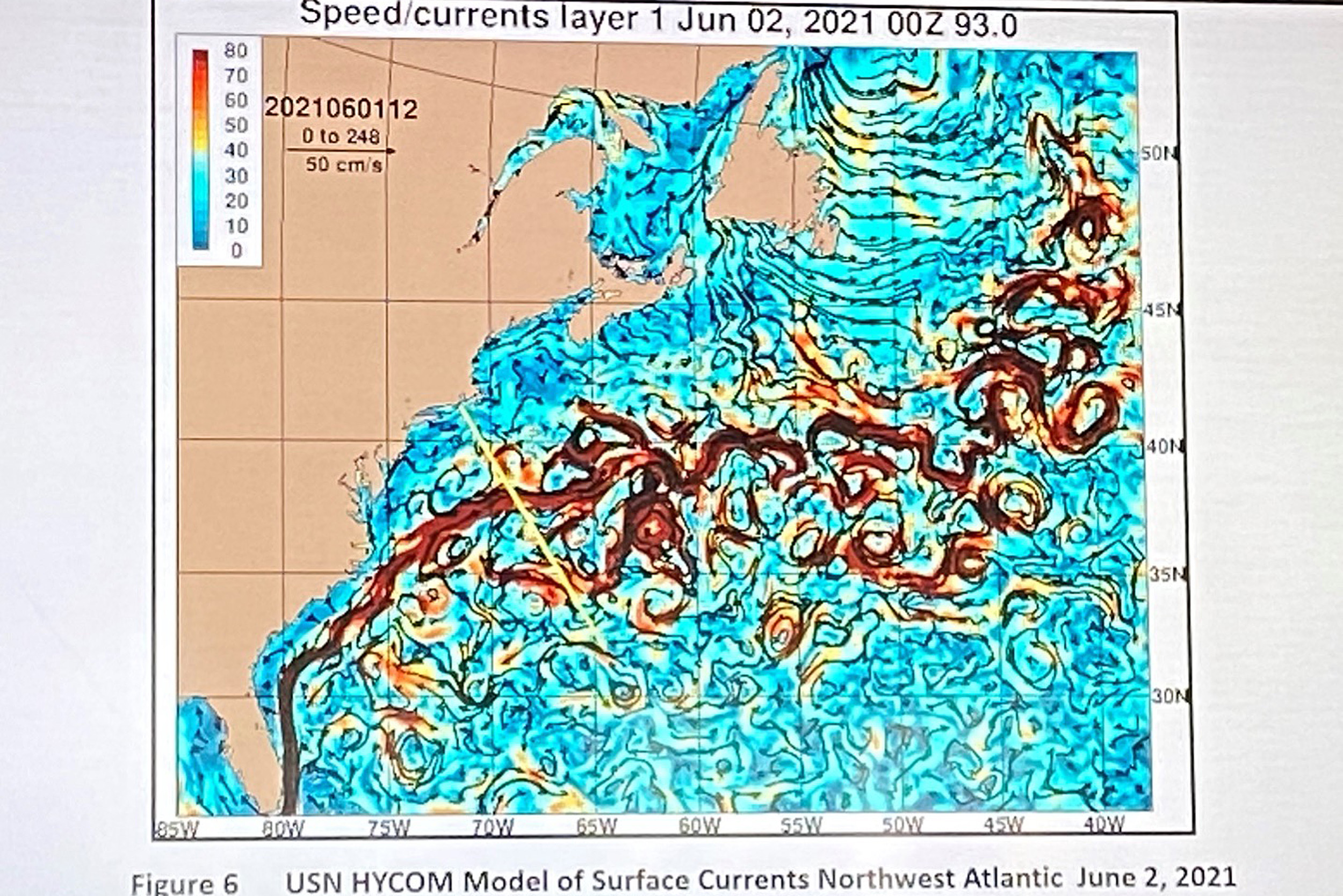

A map tracking the surface currents in the Northwest Atlantic on June 2, 2021.

Hammitt fell into the sleep-wake rhythm he would stick to for the next few days, eating quick-cooking, one-pot meals and snack bars. Seas built to six to eight feet, sending waves breaking over the bow and foaming along half the Reveille’s length before splashing back over the side.

“People don’t appreciate that offshore boats are being pushed around all the time. It’s not dangerous, but you always have to be bracing, or — if you’re in a bunk — leaning against the downwind side, the downhill side,” Hammitt said. “It’s just constant motion. If you’re standing up doing something you have to be braced, because you can’t just stand there.”

During his waking moments, Hammitt not only kept an eye on the sails and the weather, he also had to plot the boat’s course through the Gulf Stream, which, though often described as a river of warm tropical water coursing north off the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, actually has many eddies swirling off the main current. As part of their preparation, racers studied detailed weather reports and forecasts of the Gulf Stream. A racer plotting a course through the eddies could find areas where the currents actually flowed south, opposite the main current’s direction, and pick up a knot or two in speed — or a little more than 1 or 2 mph.

“That’s always been an important part of offshore racing, figuring out the strategy, where you want to go, because the straight line isn’t necessarily the best,” Hammitt said. “And here of course, there’s the Gulf Stream that you have to cross, which has a lot of meanders to it and eddies that spin off the north and south side of it. If you’re on the right side of those eddies, you can get maybe two knots’ boost. If you’re on the wrong side, you can have two knots pushing you the wrong way.”

Jim Hammitt (right) and race partner John Paulling leave Bermuda after the start of the doublehanded return leg of the Bermuda One-Two Yacht Race.

Photo by Bob Fitzgerald

Hammitt and the Reveille slowed significantly over the leg’s last 200 miles as the winds fell. Other competitors were held up as well, and Hammitt’s was the fourth boat to arrive in Bermuda. Each of the three ahead of him, however, were newer, sleek racers, and the race organizers applied a handicapping system that took boat design into account in order to level the playing field. When the calculations were completed, Hammitt was awarded first place for the leg.

Though a relative newcomer among East Coast ocean sailors, Hammitt was far from a novice at the sport. He was introduced to open ocean sailing off the California coast, aboard his parents’ boats as they regularly made the 25-mile sail to Catalina Island and the 60-mile sail to Santa Cruz Island. His father began crewing aboard racing boats and, as Hammitt got older, he accompanied him on overnight races off Southern California. When he was in high school, Hammitt began crewing on boats without his father, and as a junior, raced from Newport Beach 800 miles to Cabo San Lucas at the southern tip of Baja California. The following summer, he crewed in the 2,000-mile-plus Transpac, run between California and Hawaii.

After high school, Hammitt headed to Harvard, where he found himself sharing a room with three others who shared a sailing background. One was Jeremy Henderson, who would join Hammitt on the sailing team.

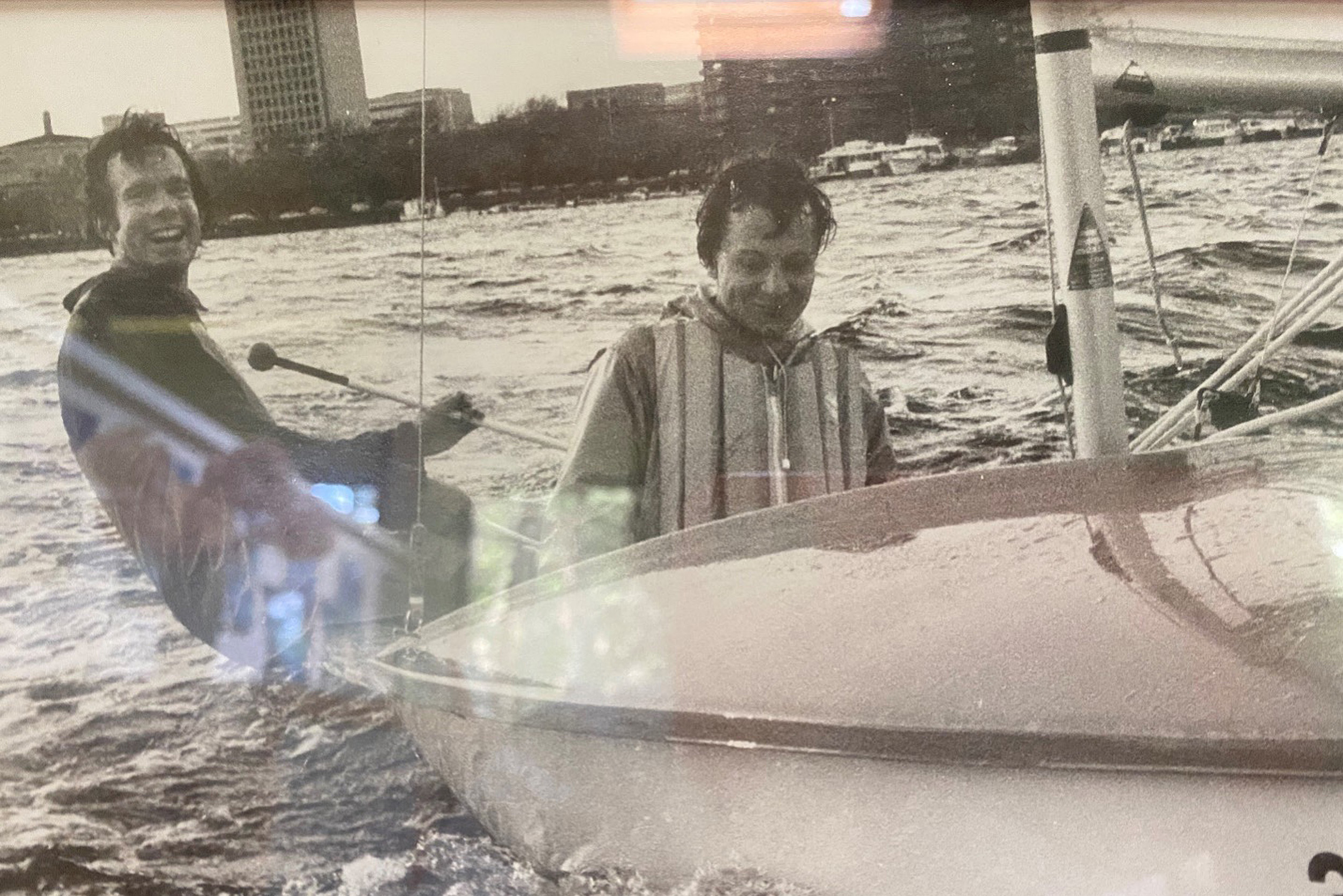

Jim Hammitt ’77 (left) sailing a Lark dinghy on the Charles River with teammate Charlie Coolidge ’77 in the fall of 1976.

Photo by Russell Long

“We weren’t all equally committed to racing, but we all had sailing in our lives previously. Of the four of us, only Jim and I joined the sailing team,” Henderson said. “The Harvard admissions officer, or whoever does the housing assignments actually got it right, because it led to a lifelong friendship.”

Hammitt also made friends with his co-captain, Russell Long, with whom he’d continue to sail after college. Their team ranked as high as number seven nationally, Long said, and Hammitt was named an All American. After graduating in 1978, he headed the short distance to the Harvard Kennedy School, where he earned a master’s in public policy in 1981. He then embarked on a public policy doctoral program, moving back to L.A. while working on his dissertation. He took a job at policy think tank Rand Corp. and competed in the 1984 Olympic trials aboard a Tornado-class catamaran before getting his Ph.D. in 1988.

By the early 1990s, Hammitt, married with two kids, still managed to race regularly. But when he accepted an appointment at Harvard in 1993, the move brought with it new academic responsibilities. With neither a boat nor connections in the East Coast sailing community, sailing tumbled down the priority list.

“Once we moved here with our sons — they were 2 and 4 — sailing was not a big part of our lives,” Klein said. For several years, the pair buckled down and got on with their responsibilities but both felt they were missing out. Finally, in 2001, the couple decided their sailing hiatus was over.

“We just came to the point where we’re like, ‘We really need to get sailing back into our lives and make it be a big thing,’” Klein said.

The Hammitt family sailing from Gibraltar to Morocco after crossing the Atlantic aboard Reveille in 2005. Galen Hammitt, 14 (from left), Rob Hammitt, 16, Jim Hammitt, and Susie Klein.

Photo by Fred Cottrell

Later that year, they found the Reveille, a 1985 Sigma 41, one of an older generation of racer-cruisers, hybrid boats with decent enough speed for racing, but whose design also makes them comfortable for casual cruising. They fell in love and, by the following February, welcomed the Reveille to the family.

Not surprisingly, the return to boat ownership jump-started their sailing lives. In 2005, Hammitt was going on sabbatical, taking an appointment at the Toulouse School of Economics in France. The couple decided to sail the Reveille across the Atlantic with their sons, then 14 and 16. To prepare the boat, the family sailed the Reveille in the 2004 Newport-Bermuda Race. The Atlantic crossing took 12 days to the Azores and seven more to Gibraltar. They sailed to Morocco, Spain, and the Balearic Islands before heading to Toulouse for the academic year. For the next few years, they traveled back and forth between Boston and the Mediterranean as far east as Turkey, spending summers aboard the Reveille and returning for the school year.

Over his decades at the helm, Hammitt has spent many months, if not years, at sea. And, though competition does add spice to the endeavor, he says it’s not navigating sailing’s complexities or conquering its hazards that draws him back to the open ocean. Instead, it’s the immersive nature of life there, its simplicity, and its beauty.

“Being at sea is a really pure form of living,” Hammitt said. “All you care about are the basics of sleeping, eating, taking care of yourself, taking care of the boat, making sure everything’s working, and being totally aware of the weather.”

Paulling, Hammitt’s crew member for the second leg, arrived a few days before the start of the race. The forecast indicated the weather wouldn’t be as benign on the return leg. Indeed, shortly after leaving they got hit by a squall with gusts near 45 miles per hour. The Reveille got knocked down — its mast almost in the water — which sent Paulling, off watch and below, scrambling on deck to help get the boat under control.

Neither man was too concerned by the episode. In fact, though some might think storms are best avoided, to Hammitt, the squalls represent a chance to take advantage of faster winds.

“Being at sea is a really pure form of living. All you care about are the basics of sleeping, eating, taking care of yourself, taking care of the boat, making sure everything’s working, and being totally aware of the weather.”

Jim Hammitt

“A squall is circulating counterclockwise — it’s a low-pressure system — and you’ll have different wind directions depending on where you are,” Hammitt said. “On one side, it’s reinforcing the prevailing winds and on the other it’s countering the prevailing winds. You want to be on the side reinforcing it.”

As they approached the Gulf Stream, the weather worsened again, with lightning, heavy winds, and torrential rain, followed by several hours of light air. The reward, though, was that the current pushed them in the right direction. As they approached the finish line, they saw a flock of birds with what was likely a whale feeding beneath, Paulling said. A little later they spotted a second flock and saw tuna jumping out of the water nearby. With the wind behind them for the first time, they set the Reveille’s big blue and white, parachute-like, spinnaker.

“That just carried us through the whole day,” Paulling said. “It was just a beautiful day of sailing.”

They arrived in Newport a bit less than five days after the start, placing second on the leg but doing well enough for first overall.

“Some of these guys have done this a number of times, and here comes this guy with this older boat, and nobody knows him,” Paulling said. “He hasn’t been racing for years, and his racing reputation isn’t very well known on the East Coast. He gets first place going down and I was thinking, ‘I hope we do well to back it up, prove it wasn’t a fluke.’ I think we did.”