Massage helps injured muscles heal faster and stronger

Study confirms link between mechanotherapy and immunotherapy in muscle regeneration in mice

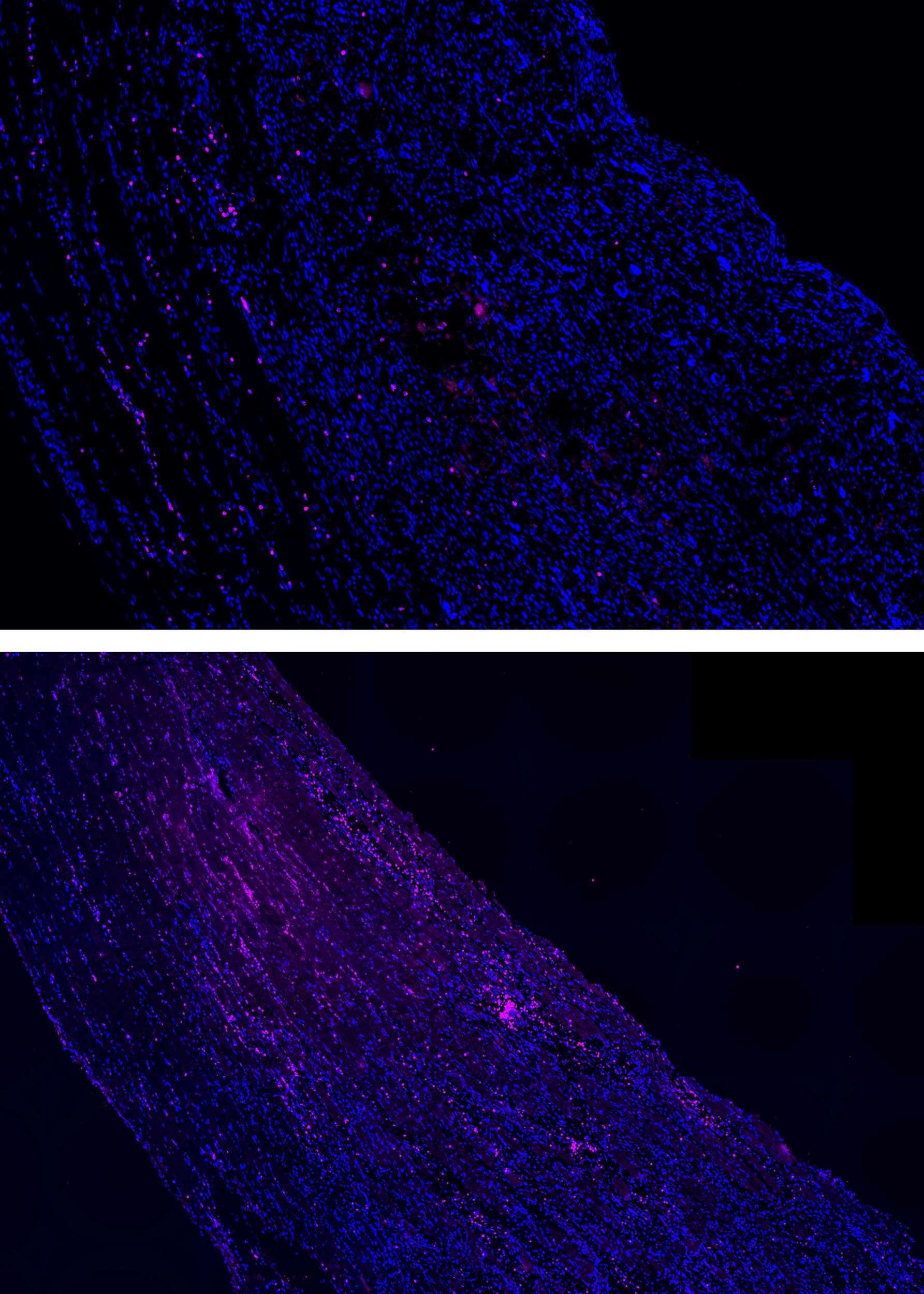

When injured mouse muscles were treated with mechanotherapy for three days (top), they displayed a significantly reduced number of neutrophils (in pink) compared to untreated muscles (bottom).

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Massages feel good, but do they actually speed muscle recovery? Turns out, they do. Scientists at the Wyss Institute and Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences applied precise, repeated forces to injured mouse leg muscles and found that they recovered stronger and faster than untreated muscles, likely because the compression squeezed inflammation-causing cells out of the muscle tissue.

Using a custom-designed robotic system to deliver consistent and tunable compressive forces to mice’s leg muscles, researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and SEAS found that this mechanical loading (ML) rapidly clears immune cells called neutrophils out of severely injured muscle tissue. This process also removed inflammatory cytokines released by neutrophils from the muscles, enhancing the process of muscle fiber regeneration. The research is published in Science Translational Medicine.

“Lots of people have been trying to study the beneficial effects of massage and other mechanotherapies on the body, but up to this point it hadn’t been done in a systematic, reproducible way,” said first author Bo Ri Seo, who is a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Dave Mooney at the Wyss Institute and SEAS. “Our work shows a very clear connection between mechanical stimulation and immune function. This has promise for regenerating a wide variety of tissues including bone, tendon, hair, and skin, and can also be used in patients with diseases that prevent the use of drug-based interventions.”

A more meticulous massage gun

Seo and her co-authors started exploring the effects of mechanotherapy on injured tissues in mice several years ago, and found that it doubled the rate of muscle regeneration and reduced tissue scarring over the course of two weeks. Excited by the idea that mechanical stimulation alone can foster regeneration and enhance muscle function, the team decided to probe more deeply into exactly how that process worked in the body, and to figure out what parameters would maximize healing.

They teamed up with soft robotics experts in the Harvard Biodesign Lab, led by Wyss Associate Faculty member Conor Walsh to create a small device that used sensors and actuators to monitor and control the force applied to the limb of a mouse. The team experimented with applying force to mice’s leg muscles via a soft silicone tip and used ultrasound to get a look at what happened to the tissue in response. They observed that the muscles experienced a strain of between 10 to 40 percent, confirming that the tissues were experiencing mechanical force. They also used those ultrasound imaging data to develop and validate a computational model that could predict the amount of tissue strain under different loading forces.

“This has promise for regenerating a wide variety of tissues including bone, tendon, hair, and skin, and can also be used in patients with diseases that prevent the use of drug-based interventions.”

Bo Ri Seo, Wyss Institute

They then applied consistent, repeated force to injured muscles for 14 days. While both treated and untreated muscles displayed a reduction in the amount of damaged muscle fibers, the reduction was more pronounced and the cross-sectional area of the fibers was larger in the treated muscle, indicating that treatment had led to greater repair and strength recovery. The greater the force applied during treatment, the stronger the injured muscles became, confirming that mechanotherapy improves muscle recovery after injury. But how?

Evicting neutrophils to enhance regeneration

To answer that question, the scientists performed a detailed biological assessment, analyzing a wide range of inflammation-related factors called cytokines and chemokines in untreated vs. treated muscles. A subset of cytokines was dramatically lower in treated muscles after three days of mechanotherapy, and these cytokines are associated with the movement of immune cells called neutrophils, which play many roles in the inflammation process. Treated muscles also had fewer neutrophils in their tissue than untreated muscles, suggesting that the reduction in cytokines that attract them had caused the decrease in neutrophil infiltration.

The team had a hunch that the force applied to the muscle by the mechanotherapy effectively squeezed the neutrophils and cytokines out of the injured tissue. They confirmed this theory by injecting fluorescent molecules into the muscles and observing that the movement of the molecules was more significant with force application, supporting the idea that it helped to flush out the muscle tissue.

To pick apart what effect the neutrophils and their associated cytokines have on regenerating muscle fibers, the scientists performed in vitro studies in which they grew muscle progenitor cells (MPCs) in a medium in which neutrophils had previously been grown. They found that the number of MPCs increased, but the rate at which they differentiated (developed into other cell types) decreased, suggesting that neutrophil-secreted factors stimulate the growth of muscle cells, but the prolonged presence of those factors impairs the production of new muscle fibers.

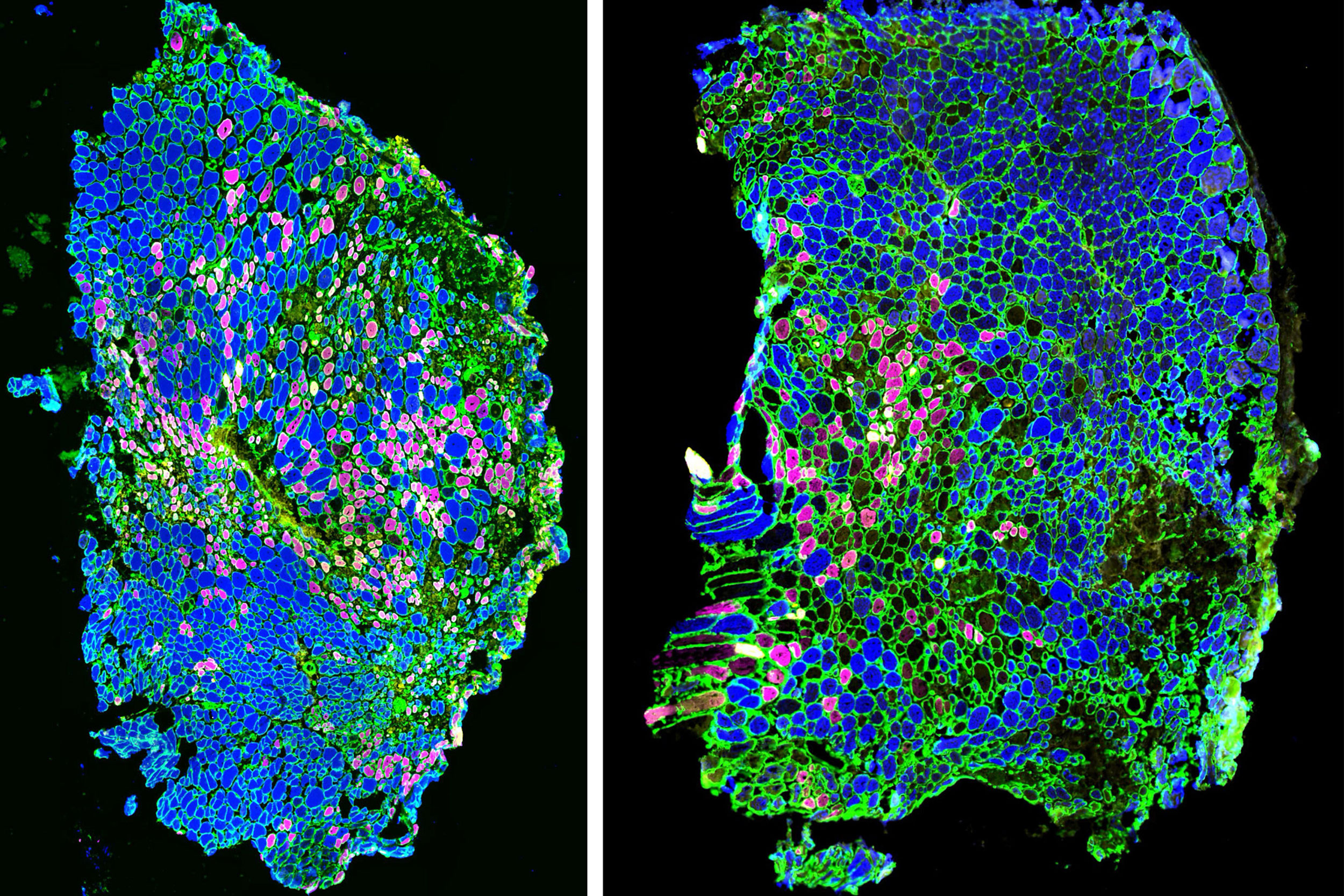

Immunofluorescence images show that when an injured muscle is treated with mechanotherapy (right), its muscle fiber type composition changes compared to untreated muscles (left). The composition of the treated muscle is more similar to that of healthy muscle, implying that treatment helps restore proper muscle function.

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

“Neutrophils are known to kill and clear out pathogens and damaged tissue, but in this study we identified their direct impacts on muscle progenitor cell behaviors,” said co-second author Stephanie McNamara, a former post-graduate fellow at the Wyss Institute who is now an M.D.-Ph.D. student at Harvard Medical School and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “While the inflammatory response is important for regeneration in the initial stages of healing, it is equally important that inflammation is quickly resolved to enable the regenerative processes to run its full course.”

Seo and her colleagues then turned back to their in vivo model and analyzed the types of muscle fibers in the treated vs. untreated mice 14 days after injury. They found that type IIX fibers were prevalent in healthy muscle and treated muscle, but untreated injured muscle contained smaller numbers of type IIX fibers and increased numbers of type IIA fibers. This difference explained the enlarged fiber size and greater force production of treated muscles, as IIX fibers produce more force than IIA fibers.

Finally, the team homed in on the optimal amount of time for neutrophil presence in injured muscle by depleting neutrophils in the mice on the third day after injury. The treated mice’s muscles showed larger fiber size and greater strength recovery than those in untreated mice, confirming that while neutrophils are necessary in the earliest stages of injury recovery, getting them out of the injury site early leads to improved muscle regeneration.

“These findings are remarkable because they indicate that we can influence the function of the body’s immune system in a drug-free, non-invasive way,” said Walsh, who is also the Paul A. Maeder Professor of Engineering and Applied Science at SEAS and whose group is experienced in developing wearable technology for diagnosing and treating disease. “This provides great motivation for the development of external, mechanical interventions to help accelerate and improve muscle and tissue healing that have the potential to be rapidly translated to the clinic.”

The team is continuing to investigate this line of research with multiple projects in the lab. They plan to validate this mechanotherpeutic approach in larger animals, with the goal of being able to test its efficacy on humans. They also hope to test it on different types of injuries, age-related muscle loss, and muscle performance enhancement.

“The fields of mechanotherapy and immunotherapy rarely interact with each other, but this work is a testament to how crucial it is to consider both physical and biological elements when studying and working to improve human health,” said Mooney, who is the corresponding author of the paper and the Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.

Additional authors of the paper include Benjamin Freedman, Brian Kwee, Sungmin Nam, Irene de Lázaro, Max Darnell, Jonathan Alvarez, and Maxence Dellacherie from the Wyss Institute and SEAS, and Herman H. Vandenburgh from Brown University.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research under Award Number R01DE013349, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development under Award Number P2CHD086843, the Materials and Research Science and Engineering Centers grant award DMR-1420570 from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute of Health (F32 AG057135), and the National Cancer Institute (U01CA214369).