In 1989, archivist Irina Klyagin made a remarkable discovery that changed Russian ballet scholarship.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Prized manuscript — and valuable lesson — unearthed in Soviet archive

Librarian discovers value of historical documents along with émigré ballerina’s memoir, hidden by repressive regime

Viewing the “special collections” in Moscow’s Lenin Library was not easy in the late 1980s.

It meant first undergoing a security clearance and then being taken to an unmarked room to sort through decades of materials confiscated by the KGB. For librarian and archivist Irina Klyagin, it also meant making a discovery that changed ballet scholarship.

Klyagin, who has worked at Houghton Library for nearly 20 years, is an expert in Russian ballet at the turn of the 20th century. One of her greatest contributions to the scholarship was her 1989 discovery of an original typescript memoir by Russian ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska, a savvy, fiery character who loomed large in an influential period for dance. Discovering the memoir and helping make it more available marked a key moment in Klyagin’s career as an archivist.

“It was my first experience of finding an item in an archival institution, and behind it there’s a whole story,” Klyagin said. “A whole life.”

At the time, Klyagin was working for Russian arts magazine Theatre Life and was given research access to the special collections of what is now called the Central Russian Library. The special collections were so restricted, Klyagin said, that until she was authorized to visit, she’d never even heard of them.

Working in those archives for a year, Klyagin came to understand both the beauty of learning through access to historical documents and the tragedy of the Soviet government’s near blanket denial of access to a vast array of new as well as old materials to its people.

“We were so information-hungry,” she said. “Even in the late 1980s, as things were less restricted, it was virtually impossible to access anything published outside the Soviet Union. But the library was actually buying books published in the West and keeping them in the special collections, which didn’t officially exist. You needed to be ideologically solid and politically trusted to access them.”

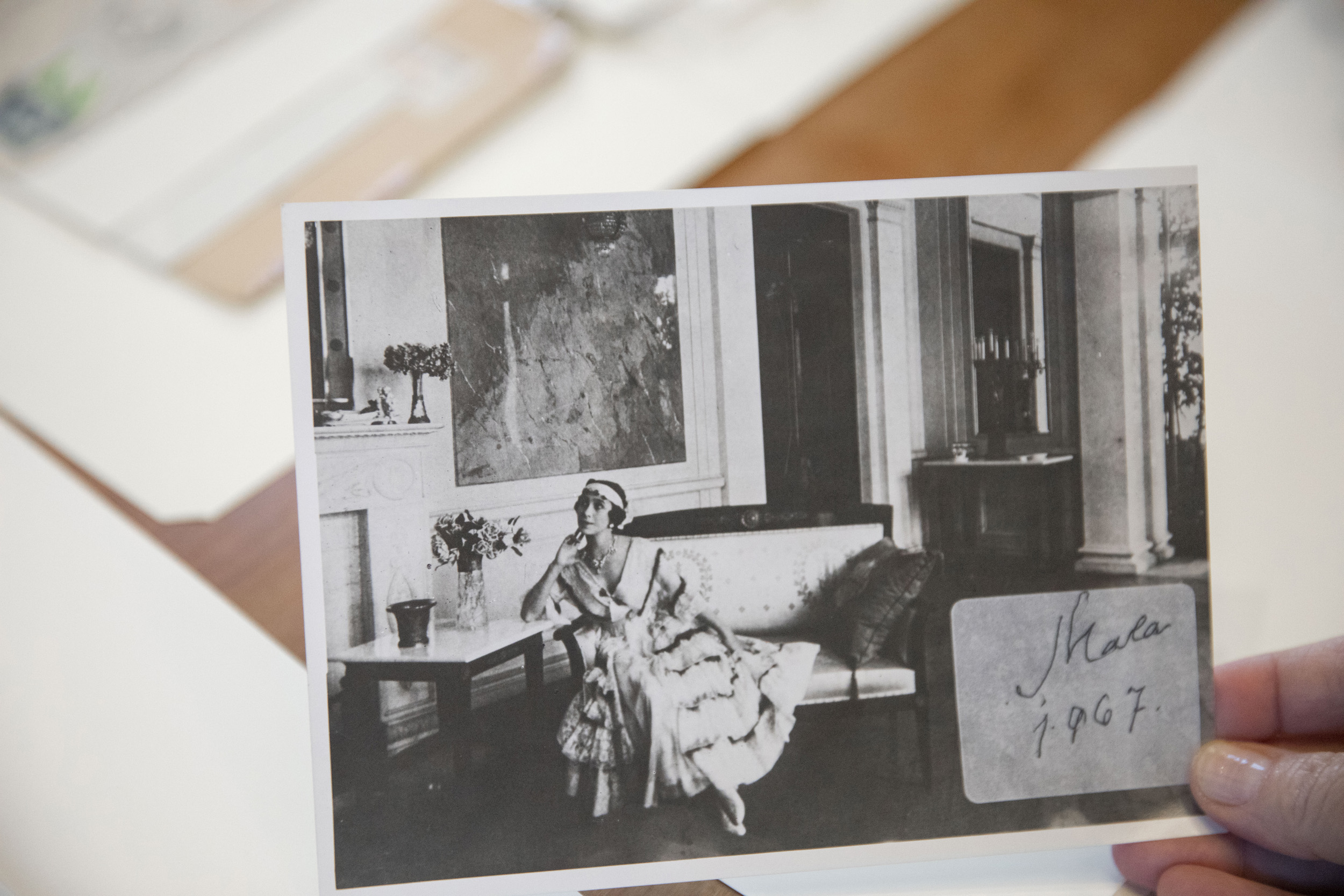

It was there that Klyagin stumbled across the Kschessinska memoirs. A prima ballerina of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres, Kschessinska was notorious in her time for an affair with future Czar Nicholas II and two other grand dukes.

She is also remembered today for revolutionizing ballet technique, said Daria Khitrova, a scholar at Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

“Kschessinska wasn’t the first ballet dancer to be a mistress of powerful men,” the Slavic historian said, “but she was the first, despite the comfort of this status, to tirelessly perfect her art, to achieve technical skills almost no one in Europe could achieve.”

The dancer’s extraordinary performance in “Swan Lake” in the 1890s is arguably why that ballet is still popular today, Khitrova added.

Tim Scholl, Oberlin College professor and ballet scholar, also noted Kschessinska’s immense wealth and political cachet.

“If there were a Forbes ‘25 Most Powerful Women’ list in 1900, Kschessinska would have been on it,” he said.

But the Soviet regime in the mid-20th century wanted the ballerina forgotten, owing to her romantic involvement with several members of the royal Romanov family, and her escape to France following the Russian Revolution. A French version of Kschessinska’s memoir was published in 1961, but only a few Russian academics knew about it, and by the 1980s, the Russian public knew just rumors and gossip about Kschessinska told through the years. No one — not scholars, and certainly not the public — knew there was a more detailed, unfiltered version of the ballerina’s memoir written in her native Russian, or that it had been in a library in Moscow for years.

“Kschessinska was legendary for some and notorious for others, but nobody expected to hear from her in her own voice,” Khitrova said. The Russian memoir “was a revelation.”

“It changed not just scholars’ understanding of Kschessinska as a ballerina and a person, but of the whole period at the turn of the century,” added Klyagin.

For Klyagin herself, the discovery was eye-opening. The historical figure became three-dimensional for her as she worked with the memoirs and so “marked a change in my attitude toward archives,” she said.

“I see archives, now, as the richest source of real life,” Klyagin said. “You never know what detail, what strange twist, will come together and open up a new picture for you.”

As exciting as the discovery was from a scholarly perspective, it was upsetting from a political one, as it illustrated the uphill battle waged by Russian academics against decades of censorship and knowledge suppression.

After Theatre Life began publishing memoir excerpts, Klyagin was contacted by a relative of Kschessinska’s who helped her piece together how the manuscript had ended up in the Lenin Library.

“I see archives, now, as the richest source of real life. You never know what detail, what strange twist, will come together and open up a new picture for you.”

Irina Klyagin

According to this relative, Kschessinska planned to give the original Russian memoir to the Tchaikovsky House-Museum in Moscow, but the museum never received it. The supposed museum representative who met with Kschessinska was actually a member of the KGB, who confiscated the manuscript. It was put into the special collections, where it remained for almost 30 years with thousands of other voices the Soviet Union didn’t want heard.

The secret archives comprised not just materials published in the West, Klyagin explained, but papers and books confiscated from Russian citizens arrested in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of the books’ former owners were imprisoned. Others were executed. Klyagin and other scholars given access to the special collections became familiar with seeing some books stamped with special ink — a grim distinction of the materials’ origins.

“It was really disheartening to learn some of the materials I was looking at had come from prisoners,” Klyagin said.

She still wonders at times about those items and the people whose stories they told.

“You can’t really learn anything about the present or future without knowing the past,” she said. “When the past is suppressed — or in the case of the Soviet Union, reinvented — it’s a terrible distortion.”

Working with archives in the U.S. for the last three decades has only strengthened this opinion. Her first job here, in 1991, was in the dance division of the New York Public Library, where she worked with Russian manuscript collections and had access to all the information she wanted.

Scholl, the Oberlin ballet scholar and Klyagin’s friend, said the period in which Klyagin found the ballerina’s typescript took place during a brief time when things were less restricted. Sometime after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the doors again slammed shut. In fact, on a 2014 trip to Russia, Scholl was warned not to go to the archives.

“They were rounding up American graduate students who didn’t have the proper credentials,” he said. “That was really chilling for me. It was the end of me trying to do research in the archives there.”

As restrictions tighten again in Russia, Klyagin said she’s sure there are some stories that remain locked in the special collections in the Central Russian Library.

But Kschessinska’s story, at least, is now known. Her Russian memoir is “still all over the shelves” in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Scholl said, and he still uses it as a source for his own research. Houghton holds a copy of the Russian memoir as well as every edition of Theatre Life, the magazine in which the excerpts were originally published.

This is thanks to Klyagin, Scholl said.

“Now I see that time when Irina and I were working in the archives in Russia as this glorious period when things were possible there,” he said. “Especially for someone with Irina’s courage and determination and skill.”

In her work at Houghton now, Klyagin processes and analyzes rare materials for the Harvard Theatre Collection, including translating Russian literature and materials related to dance and theater. The library’s goal with most of these items is to make them accessible to as many researchers as possible — something that, given her history, really speaks to Klyagin.

“You cannot overestimate the importance of providing access, of preserving and making open anything we can,” she said. “The chance to read a document and try to place it in a cultural context, analyze it for yourself … for me, that’s everything.”