Props from the Apple+ TV series “Dickinson” were donated to Houghton Library, marking it a first for the library.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Belle of Amherst 2.0 (feat. Emily D)

Production archive materials donated by TV series ‘Dickinson’ arrive at Houghton

Telling the story but telling it slant.

When many people think of Emily Dickinson, they think reclusive and dark, never came to fame during her lifetime, cat lady material. The Apple+ TV series “Dickinson” aims to portray the 19th-century poet through a more contemporary lens. This Emily is angsty, ambitious, loves raging parties (twerking to the likes of Carnage and Cakes Da Killa), toys with opium, hangs with gender-fluid friends (and Walt Whitman at a gay bar), and has a romantic thing with her future sister-in-law.

Despite its wild, absurdist modern take, the showrunners took great pains to create realistic and accurate props to help tell the story and as an apparent foil to the remade Belle of Amherst. The three-season comedy will end on Dec. 24, and the show has donated its production archive to the Emily Dickinson Museum in her native city, as well as to Harvard’s Houghton Library.

The museum received antique furniture, costumes, lighting fixtures, and the carriage ridden by the character of Death, portrayed by rapper Wiz Khalifa (whose music also finds a prominent place in the soundtrack). These objects will be used to furnish various spaces in the main Homestead and The Evergreens, the house of Dickinson’s brother Austin and Susan, his wife and one of Emily’s best friends. The houses represent the heart of the museum.

Suffice it to say that the nature of the donation to Houghton is, like the show, a fresh take. The library is already home to more than 1,000 poems and letters from throughout Dickinson’s life, as well as some of her personal items. The library’s assistant curator of modern books and manuscripts, Christine Jacobson, approached the show’s creator, Alena Smith, for potential donations and received the scripts for all three seasons, costume designs, and architectural designs for the set builds, including both Dickinson houses.

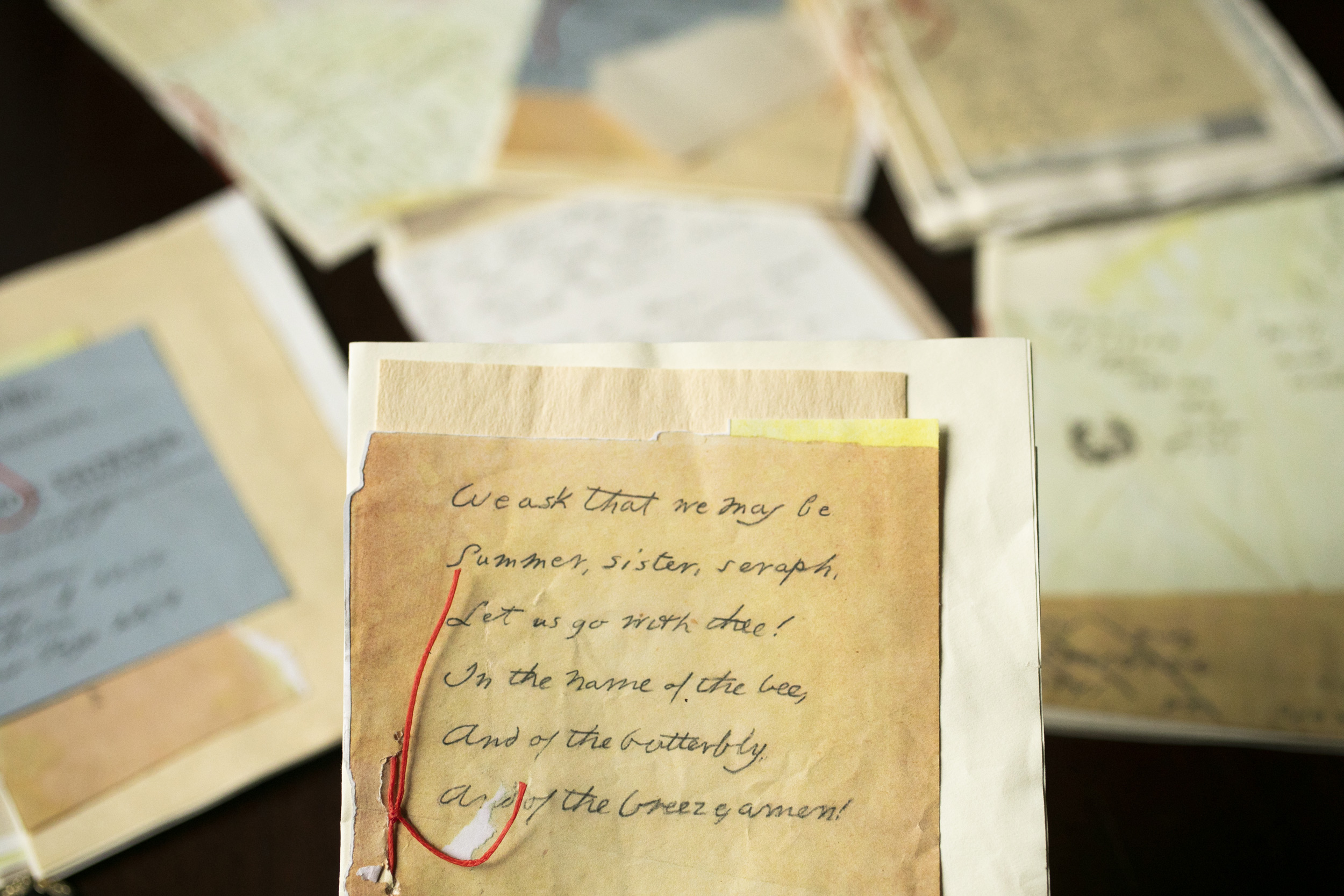

Other behind-the-scenes materials — like a scrapbook detailing the process for sourcing furniture, wallpaper, and other objects; “tone boards” created to develop the characters’s looks, settings, and scenes; and promotional posters and reviews — were also donated to the library.

The “Dickinson” gift is the first production archive from a TV series at Houghton, though the library boasts a theater collection that includes scripts and costume designs from other shows.

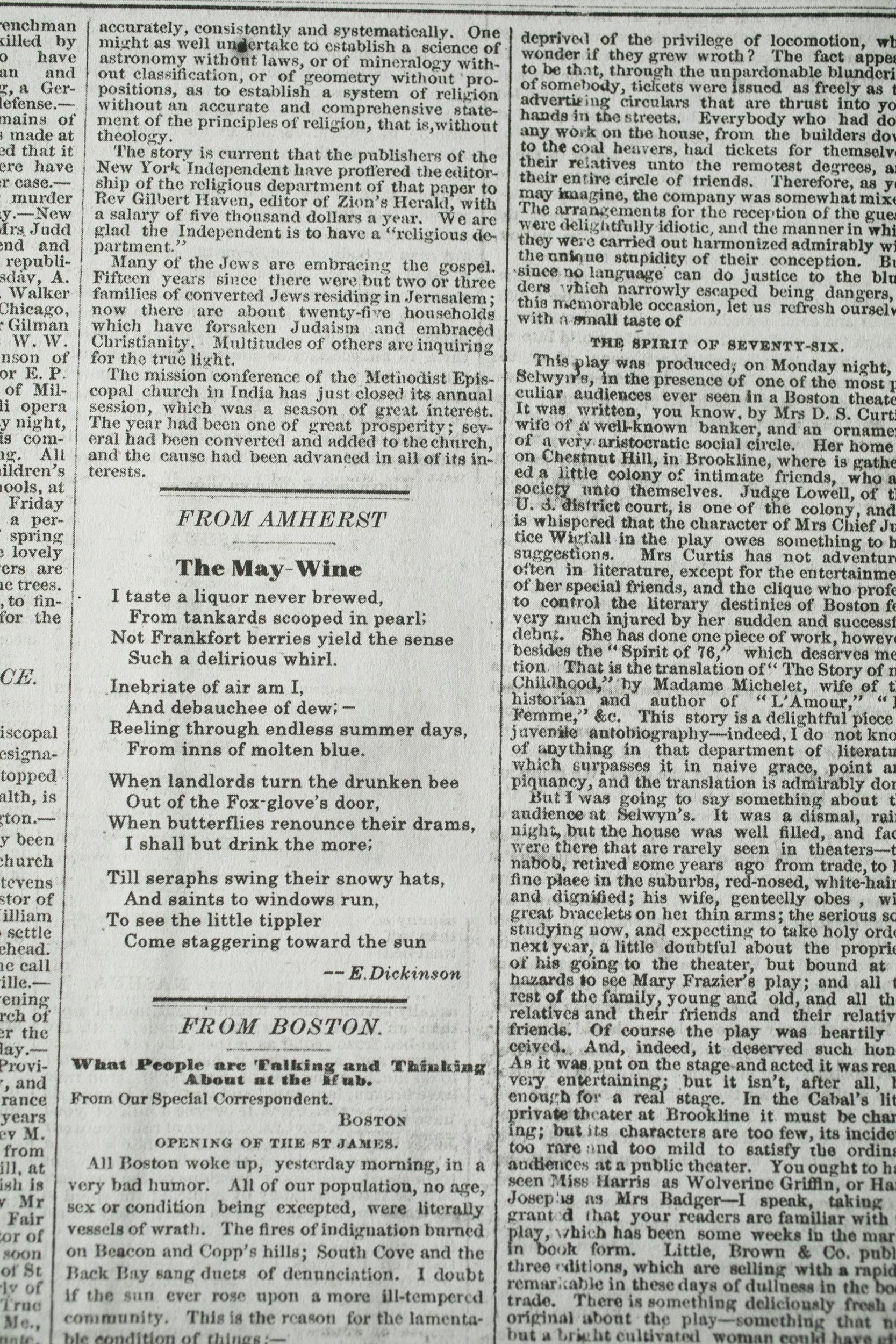

The accuracy of each item varies depending on the creators’ intent. One of the characters in the show called Henry, a fictional Black employee of the Dickinson family, publishes The Constellation, an abolitionist newspaper. This references Frederick Douglass’ North Star, his 1847 antislavery newspaper.

A poem of Dickinson’s as it appeared in the newspaper. Emily Dickinson’s handwriting was painstakingly mimicked to “look remarkably like the letters [Houghton] has,” said curator Christine Jacobson.

“Even though it’s a fictional newspaper, the text lines up exactly with the text from the edition of the North Star,” said Jacobson.

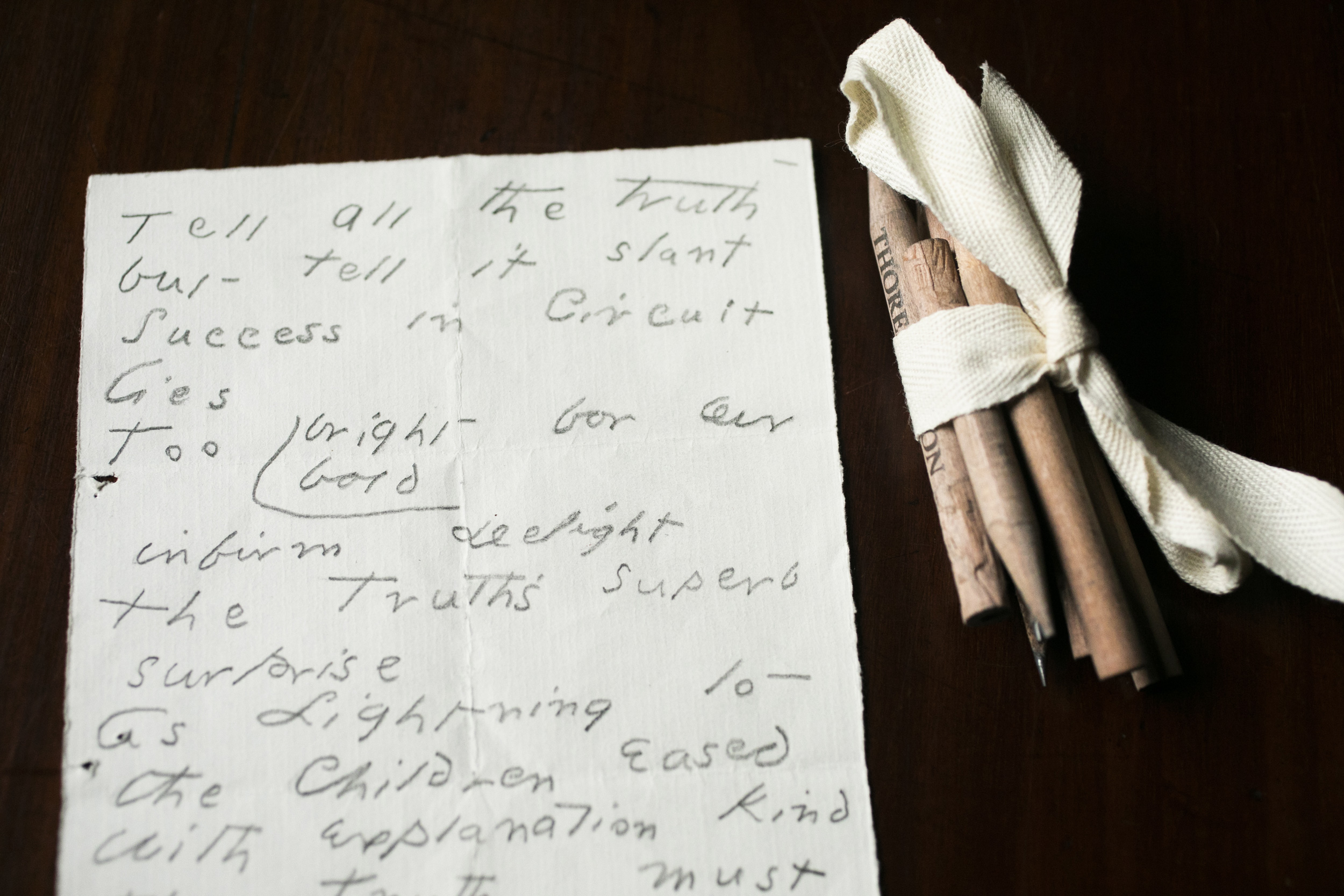

When it comes to Dickinson’s own poems and letters, the props painstakingly mimic her handwriting and “look remarkably like the letters [Houghton] has,” Jacobson said.

“Reproductions of poems, letters, newspapers, and writing in all its manifestations in 19th-century America are really important in the show,” she added.

The creators of the show were interested in the idea of Dickinson’s fascicles — hand-sewn booklets of poetry. At the end of season one, Dickinson’s character is shown sewing scraps of poems together. This representation conflates two of the poet’s creations: the fascicles and the scrap poems she wrote toward the end of her life, Jacobson said. The scrap poems were not sewn; they were written on envelopes, chocolate-bar wrappers, and other bits of paper she had on hand. The fascicles were on stationery with an insignia stamped in the top right hand corner.

“I have to assume that was a deliberate creative choice,” said Jacobson.

And then there are the portraits of Dickinson’s father, Edward, and mother, also named Emily. Eagle-eyed viewers may notice that the paintings in the show more closely resemble actors Toby Huss and Jane Krakowski, who play the elder Dickinsons.

“The production crew reached out to us very early on to secure permission to reproduce the portraits of Emily’s parents,” said Jacobson. “The camera never lingers on the portraits in the show, but it’s fun to see that they look like the actors. I think that’s representative of the show’s ethos. They care a lot about the fidelity and authenticity [of the history]. Without that rigor they wouldn’t be able to play off of it with all the modern touches.”

The Houghton collection is open to the public and is currently minimally processed, so patrons are encouraged to get in touch with staff for guidance. Even more items are to arrive because season three is still airing, so the season’s scripts, title-card collages for each episode, and other material will be added in January.

Because of the fragility of the original materials, Dickinson’s poetry and fascicles cannot be handled in person. The production archive materials are a different story.

“I’m really excited to have a poem recreated in the show on the table with students,” said Jacobson. “This is evidence of Emily Dickinson’s enduring place in popular culture.”

And that interest was clearly juiced by the popularity of the show.

“I’ve given a record number of tours [to the Emily Dickinson Room], especially among fans of the show,” Jacobson said. “I’m really excited to think this collection is sparking interest in special collections and bringing new users to the library.”