A trailblazing biologist — and beloved mentor and friend

E.O. Wilson recalled as shy but down to earth and courtly, passionate about work but generous with his time

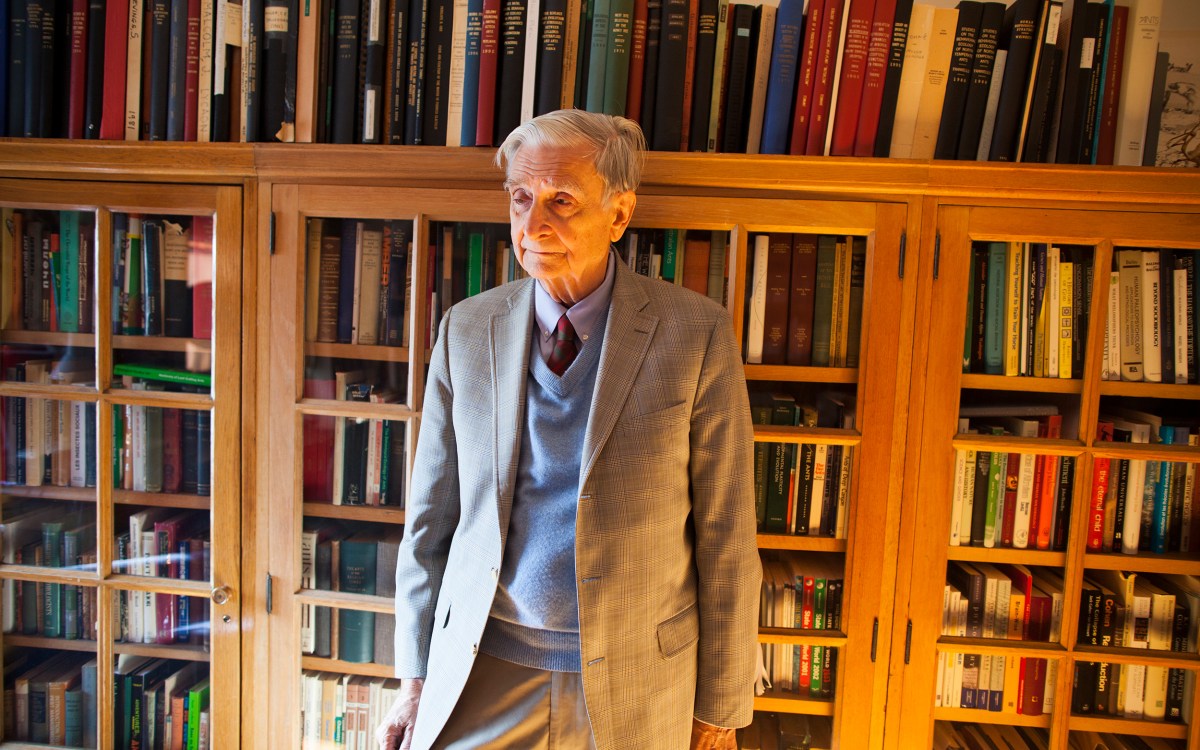

E.O. Wilson in 1994. Wilson received his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1955, joining its faculty in 1956. Wilson remained at the University the rest of his career.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

Naomi Pierce was a graduate student at Harvard in the late 1970s studying a species of butterfly at a lab in the Rocky Mountains. Her work was moving along, and everything was essentially fine. But Pierce felt ready for something more: to embark on an adventure and study the insects in the wilds of Australia. Her adviser suggested she hold off and go later on a postdoctoral fellowship. When he went on sabbatical, she happened to mention her idea while chatting with Edward O. Wilson.

“Immediately, his eyes lit up and he said, ‘Absolutely, you have to go,’” recalled Pierce, now a Harvard biology professor and curator. “It was all go, go, go! ‘Go off to Australia and see what you can find.’ I have to say, it made all the difference in the world. I probably wouldn’t have stayed in biology [without that trip] …. He had a really nice way of making you feel like your crazy idea was not so crazy after all. It was actually just what you should be doing.”

Wilson, who died late last month, was faculty emeritus from the Museum of Comparative Zoology and the Pellegrino University Professor. The celebrated biologist and author was widely known for his sage advice and rock-solid support. In fact, close colleagues and former students say they were often most struck by his humanity, his love of conversation (especially about nature), and his willingness to embrace the roles of mentor and friend, always encouraging them to follow their curiosity and fiercely pursue their ambitions.

Former teaching fellows of E.O. Wilson’s who attended his last lecture before his retirement in 1996. From left: Michael Donoghue, Kristine Forsgaard, Wilson, Naomi Pierce, Colleen Cavanaugh, and Toby Kellogg.

Courtesy of Naomi Pierce

“I would suggest to young people to look for that blank space of the frontier,” said Wilson in a 2018 interview with the Gazette. In another, he echoed a similar sentiment: “Search until you find a passion and go all out to excel in its expression.”

Sentiments Wilson lived by. Over the course of a career that began in the middle of the last century and really continued to the end, Wilson received scores of honors and awards. He was a leading expert on ants, insects, and biodiversity and became widely known as a modern-day Darwin, pioneering the field of sociobiology, which sought to explain the evolutionary basis behind social behavior.

A prolific author of academic writing and popular science and a skilled storyteller, Wilson won Pulitzer Prizes for “On Human Nature” (1979) and “The Ants” (1991). His books and love of nature inspired generations of scientists and non-scientists to appreciate and protect the natural world and served as a guiding light for the modern environmental movement.

“He was a naturalist from boyhood who ended up changing the world with a vision that was optimistic, [showing] that it’s possible to make a difference on this beautiful planet and that we have to save this paradise for future generations,” said Brian D. Farrell, a biology professor at Harvard who often worked with Wilson on biodiversity projects around the world.

Wilson was born on June 10, 1929, in Birmingham, Alabama. His parents divorced when he was young, and he was moved frequently throughout his childhood. Wilson grew up exploring the forests, swamps, and wildlife around Mobile and elsewhere. It was during one of these forays that he was left partially blind after a fishing accident, but his time in nature also sparked a lifelong fascination with ants and their social structures.

Wilson earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Alabama. In 1955 he received his Ph.D. in entomology from Harvard and that same year he married Irene Kelley of Boston. Irene passed away in August. The couple is survived by their daughter, Catherine I. Gargill, and her husband, John.

In 2009, E.O. Wilson (left) shared the stage with Nobel laureate James Watson (far right). They reflected on their lives and careers.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Wilson joined the Harvard faculty in 1956 and remained at the University the rest of his career and through retirement.

Wilson’s early career involved a lot of field work while he worked on the classification and ecology of ants in New Guinea, other Pacific islands, and Cuba and Mexico. It ultimately led to his first major discovery in 1959: While working with Harvard mathematician William H. Bossert, Wilson discovered how ants communicate through the release of chemical signals called pheromones.

Later, in 1990, Wilson and German behavioral biologist Bert Hölldobler published their Pulitzer-winning “The Ants,” detailing the insects’ anatomy, physiology, natural history, and social organization in a weighty volume that was both valued by entomologists and accessible to general readers.

“This may sound silly, but to really understand the guy and appreciate him you’d have to get into a conversation with him about ants,” said James Hanken, a professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology in the MCZ, who knew Wilson for about 20 years. “He would just almost go to a different place. I got the impression that he remembered individually every ant that he’d ever studied.”

Another of Wilson’s major works started in the early 1960s when he teamed up with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur. Over the decade, the pair developed their theory on species equilibrium and island biogeography, which was published in the seminal 1967 book “The Theory of Island Biogeography.” In it the pair sought to explain why different places have different numbers of species, and the book became a cornerstone of conservation biology and the study of biological diversity.

“They provide a mathematical explanation for how many species islands can support, using some principles of population genetics and factors like the size of the island and the distance to the mainland,” said Gonzalo Giribet, a professor in OEB and director of the MCZ. “With their formula they were able to accurately explain why certain islands had more species than others, as the island reached an equilibrium that takes into account immigration and extinction.”

Wilson and a graduate student tested the theory by successfully calculating how many species would re-emerge on small mangrove islets in the Florida Keys that had been cleared by fumigation.

“I will always remember his going into the headquarters of the Everglades National Park and asking permission to exterminate all animal life on some of their small mangrove islands because he had a theory that they would return to an equilibrium number of animal species in a short time and he wanted to test it,” said Bossert, who worked on this project as well. “They were so flabbergasted by the request that somehow they said, ‘OK.’”

What many consider to be Wilson’s most important contributions to evolutionary biology came in 1975 when he published “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.” The work explored the genetic and evolutionary roots of animal behavior and argued that genes shaped human behavior. The ideas sparked controversy, and Wilson faced accusations that he was reviving debunked theories of biological determinism but his work was eventually largely vindicated.

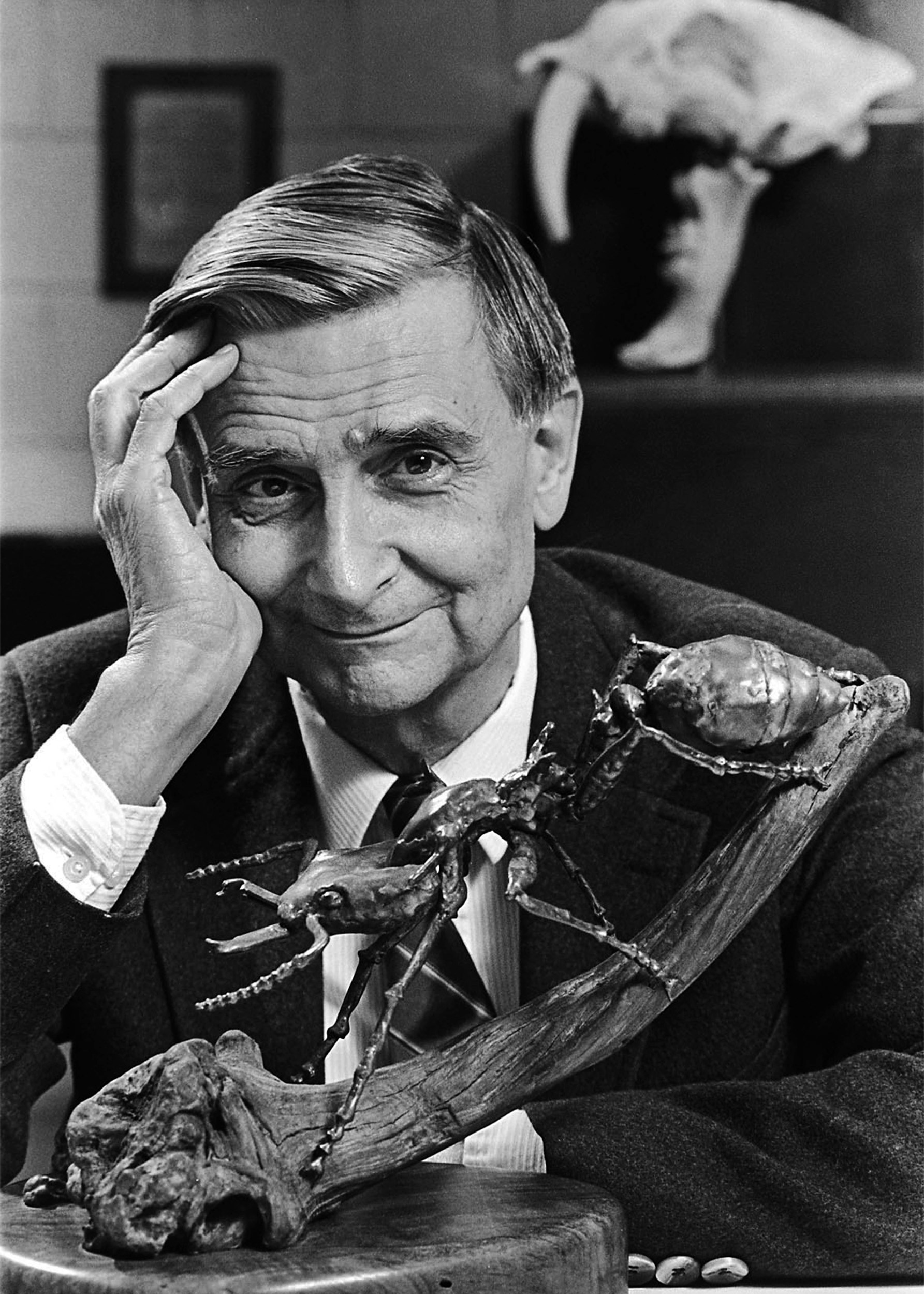

“One of the qualities I really admired about Professor Wilson was his ability to really listen and engage with whomever he was interacting with,” said Corrie S. Moreau, Ph.D. ’07, who was one of Wilson’s final advisees.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

In 1978, his ideas on the role biology plays in human culture culminated in the book “On Human Nature,” which launched evolutionary psychology and won him a Pulitzer.

In the 1980s, Wilson became focused on being a steward of nature through his writing and advocacy — an effort that would last the rest of his life. He played a central role in establishing the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and its online Encyclopedia of Life, a website that eventually will have a webpage for each of Earth’s species. He also took on projects such as restoring Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park, which was ravaged by civil war and deforestation, and created a new park in the Alabama delta near where he grew up.

Wilson published more than 400 scientific papers and 20 books, including “Biophilia,” whose title he coined to describe humanity’s relationship with nature, and also “Letters to a Young Scientist,” which he wrote with the next generation of scientists in mind. His 2016 book “Half-Earth” launched a global project with the goal of setting aside half the planet’s land for species conservation. He accrued more than 150 awards and honors from around the world, including the National Medal of Science and being named by Time magazine one of America’s 25 most influential people in 1995.

Wilson’s legion of accomplishments garnered him a type of academic superstar status, but friends and colleagues say the basically shy but courtly Southerner remained down to earth.

Giribet remembers he asked Wilson to visit his classroom to talk to students of his theory on biogeography.

“I thought he would come and say hi for a few minutes and then go, but instead he arrived to class, sat on a chair and proceeded to talk to the students (and other MCZ members who heard Ed was coming to my lecture) for over 90 minutes, Giribet said. “It was a wonderful experience that we repeated the semesters I taught biogeography.”

“One of the qualities I really admired about Professor Wilson was his ability to really listen and engage with whomever he was interacting with,” said Corrie S. Moreau, Ph.D. ’07, who was one of Wilson’s final advisees and is now a professor at Cornell University. “He never seemed to be thinking ahead or absentmindedly listening when he spoke with you.”

In fact Moreau recalls that Wilson was well known for getting into conversations that were so deep and engaging, people often lost track of time.

One conversation she found herself in with Wilson had to be ended by his assistant of 46 years, Kathy Horton. His next guest was already waiting. “He apologized to me that we would have to end our conversation, but since it was Harrison Ford — yes, the Harrison Ford — we would have to continue our conversation later.”

But then again, Moreau noted, Wilson was not without his own fan base.

“For many musicians, there are rock stars they look up to,” she said, “but for most biologists, E.O. Wilson was our rock star.”