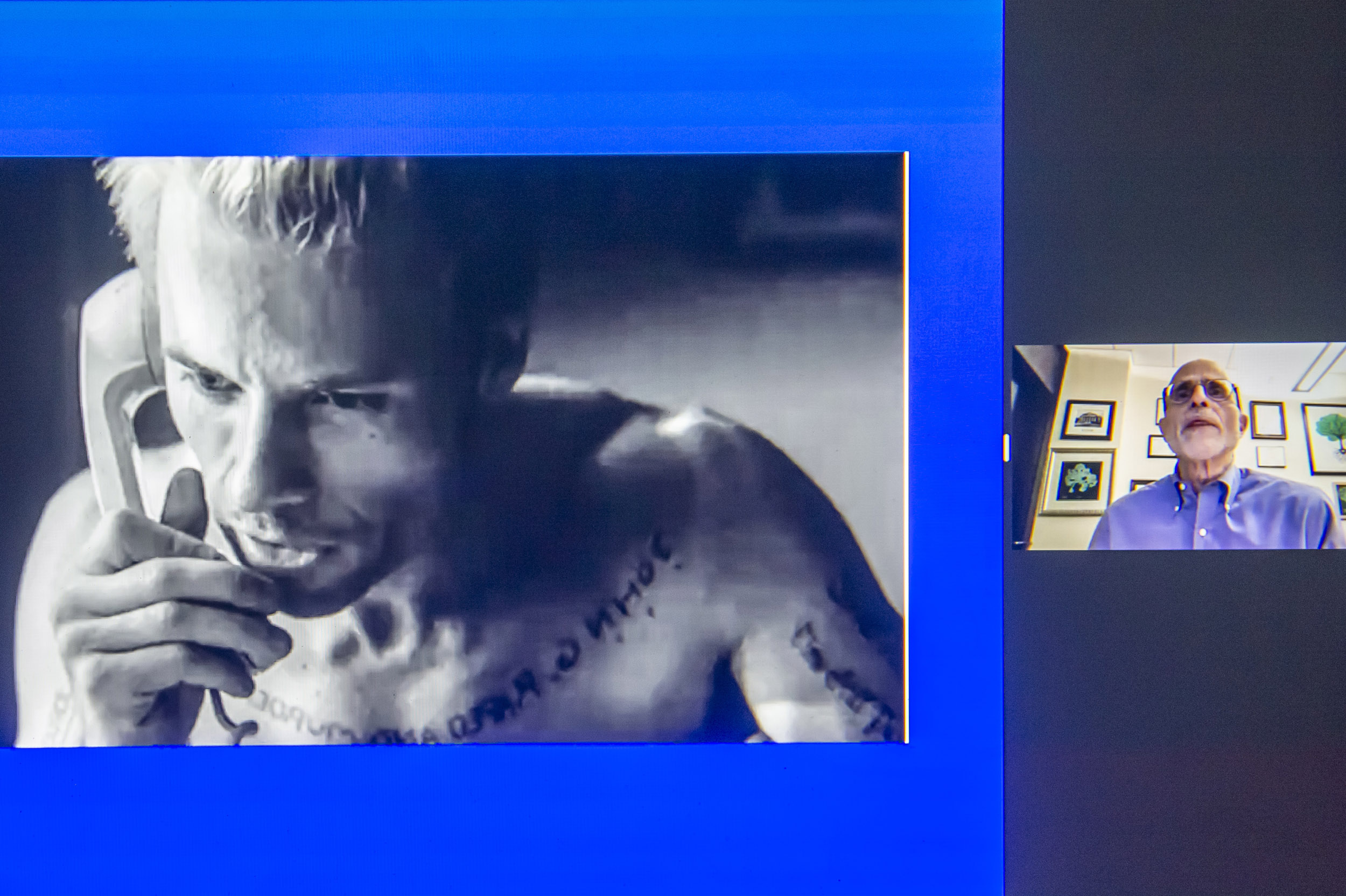

During a discussion about memory, Harvard Medical School’s Kirk R. Daffner (far right) praised the film “Memento” for not repeating the erroneous Hollywood trope that amnesia “is often caused by a blow to the head.”

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Reminders from Hollywood on memory, amnesia, personality

Psychology, philosophy scholars mine psycho-thriller ‘Memento’ for its lessons on function of recall, how it shapes who we are

Leonard is desperately trying to find the man who killed his wife and knocked him out, leaving him without the ability to form new memories of anything after that horrendous night.

That is the storyline of filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s 2000 psychological thriller “Memento,” which served as the focus for a lively online panel discussion Monday evening on memory, how it functions and shapes who we are — and how accurate Hollywood typically is in depicting all of it.

Led by moderator Kirk R. Daffner, Harvard Medical School’s J. David and Virginia Wimberly Professor of Neurology, panelists Daniel L. Schacter, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Psychology, and Susanna C. Siegel, Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy, opened the event, sponsored by the Mind Brain Behavior Interfaculty Initiative, with a discussion of the plausibility of the acclaimed film’s premise.

Leonard, played by Guy Pearce, attempts to compensate for his inability to remember by leaving himself clues — notes, Polaroid pictures, and tattoos all over his body — that apparently document what he has learned about the rape and murder of his wife. Images of this brutal act are Leonard’s last enduring memory.

Summarizing the film’s complex plot, Daffner praised it for not repeating the erroneous Hollywood trope that amnesia “is often caused by a blow to the head, which causes the loss of memory and personality and identity.” In this mistaken concept, the sufferer is still able to form new memories, and the problem is often cured by another blow to the head. “Although this account may seem silly, it is surprisingly pervasive,” said Daffner.

“There’s a very long tradition in memory research of how what we remember about the past not only reflects what happened, but our own current needs,” said panelist Daniel Schachter (left).

Schachter also praised Nolan’s understanding of anterograde amnesia, in which a person is unable to form new memories, although he noted that most cases of anterograde amnesia also entail some retrograde amnesia, or loss of memories from before the injury. (Schachter also traced the filmmaker’s insight to a Georgetown University psychology class taken by Nolan’s brother Jonathan, who used the idea for a short story.)

“The movie overall does a great job of portraying the severity of Leonard’s anterograde amnesia and clarifying the difference between what this is and the more typical movie depiction,” Schachter said.

“The way in which the movie depicts the severity is part of the genius,” he added. “The reliance on notes and photos, the continued inability to recognize other characters whom we know he knows, illustrates the severity of the deficit.”

Siegel raised the role of memory in the formation of personality. “Another thing that’s realistic and compelling is the picture of what it might be like for your mind to be limited in this way,” she said. For example, she noted, when we see Leonard reliving an argument with his wife, he doesn’t present a full range of emotions. “He’s very flat and has little affect,” she said. “Is he flat like this because of his condition? When he’s remembering that scene is he projecting the affect he has back on the scene?

“That’s a big pitfall we all face,” she said. “When we’re remembering ourselves are we remembering ourselves as we were — or are we projecting our present selves into the past?”This mutability plays a role in the story and adds to Leonard’s uncertainties. It also, said Schachter, illustrates a key understanding of memory. Noting the unreliability of eyewitness testimony, he pointed out “memories are an interpretation, not a record.” He called this plot point “a nice summary of our basic understanding of memory.”

Questions about the trustworthiness of memory and its function recurred throughout the panel, even as the participants dismissed some implausibilities of the plot — such as Leonard’s ability to remember and follow directions. As the plot unfolds, with its fragmented shifting of time, the audience has to grapple with the possibility that Leonard is intentionally misleading himself. This misdirection, the experts noted, plays on a well-known aspect of memory.

“There’s a very long tradition in memory research of how what we remember about the past not only reflects what happened, but our own current needs,” said Schachter. This theory of retrospective bias, he explained, “fits with the idea that we use our memory, or shape our memory, to fit our current needs.”

“We try to be nice to our future selves,” added Siegel. As an example, she cited a common cultivated habit of “putting things where we’ll find them.” The severity of Leonard’s case, and his awareness of it, makes this self-kindness optional. “If the future self isn’t going to appreciate this, why help him?”

Addressing one essential function of memory — it allows us to shape our own life narrative — she noted that Leonard has an advantage: Without lasting new memories, she said, “He’s a little bit freed up.”