Media Preservation Services audio engineer Bruce Gordon works to digitize and preserve analog content for Harvard.

Images courtesy of Harvard Library Preservation Services

Preserving voice of president — and thousands of others

Library preservation staff races against time to save historical media artifacts

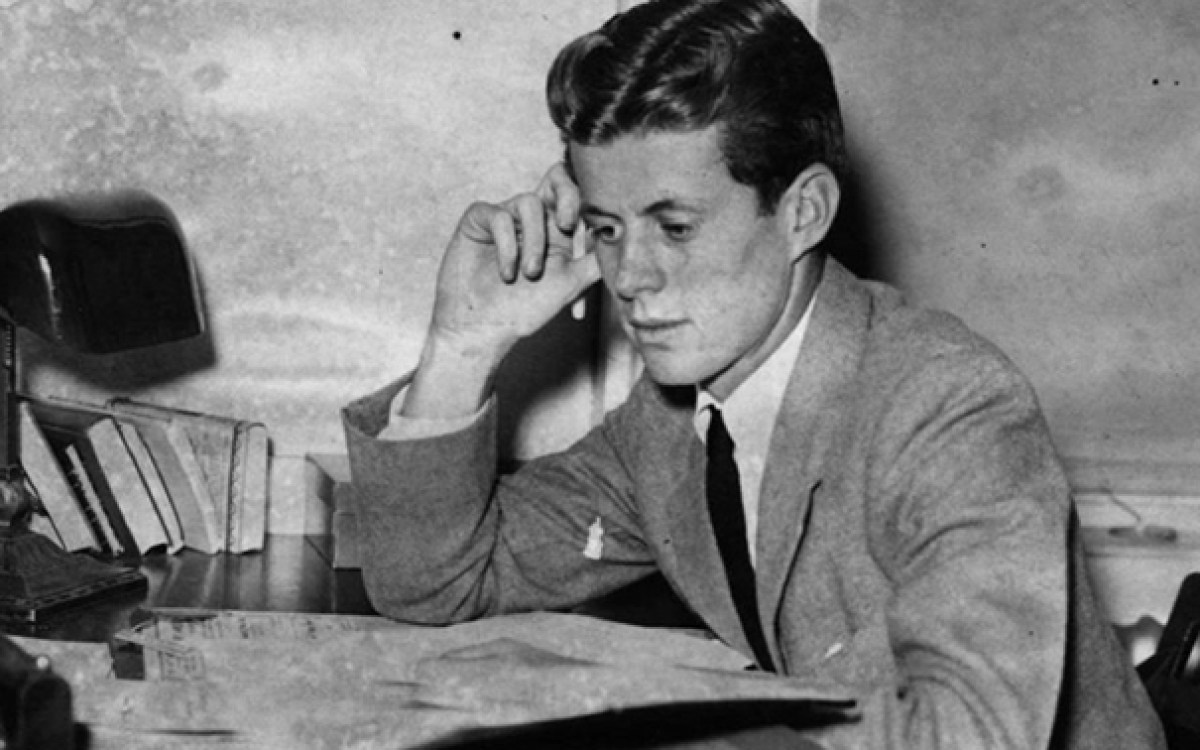

Five years ago, Harvard Library staff brought the voice of a 20-year-old John F. Kennedy to life for the world to hear.

Audio experts at the library’s Media Preservation Services were given an aluminum audio disc with Kennedy’s name on it — part of a University Archives collection of student speeches recorded during a Harvard oration course. They found a turntable that would play the disc, adjusted the recording’s somewhat obscured, uneven sound quality, and converted it into a digital audio file.

The young Kennedy’s thoughts on the Supreme Court appointment of Hugo Black now can be heard by anyone with an internet connection. That project was an example, albeit a particularly high-profile one, of the importance of the team’s mission to ensure that important historical material is saved while it’s still possible, said Director of Preservation Services Brenda Bernier.

“We’re fortunate to have on staff the top-tier expertise needed to make all kinds of media content usable by current and future scholars, including materials, like the Kennedy recording, that are one-of-a-kind and would be otherwise inaccessible,” Bernier said.

There are half a million audio and video items in Harvard Library collections that remain in analog form. These need to be assessed, digitized, and preserved. And MPS staff need to do this before the materials, such as physical discs, or the methods by which they’re played, like turntables, become unavailable, unstable, or obsolete.

“When physical materials fail, as they’re apt to do with 30-, 40-, or 50-year-old electronics, the information on them could be lost,” said Kaylie Ackerman, the head of MPS for Harvard Library. “There may be a scenario in which a recording, like this one featuring JFK, could be surfaced in the archives, but we wouldn’t be able to listen to it.”

“You can go to Harvard’s archives, open up a drawer, and see a document from 1636 that has been preserved because of responsible stewardship.”

Stephen Abrams, Digital Preservation Services

Preservation staff works with audio and video technology spanning nearly a century, from 1930s aluminum discs like the one that held the Kennedy recording to cassettes, to multichannel digital tapes.

About three years ago, Harvard Library conducted a survey of all the non-digitized media items in its collections. It concluded that just under half a million unique or rare items were “at risk.”

This means, Ackerman said, “if we do nothing, the vast majority of those items would fall out of use, and there would be no access to them.”

There’s not yet cause for alarm, though. The increasing obsolescence of analog recordings is something MPS has been aware of for years.

Harvard Preservation began its work with digital formats to preserve audio-visual material in 1997, years before many organizations acknowledged digital was the future of AV preservation, Ackerman said. And her department faced a lot of skepticism.

More like this

“But the fact that we started working with digital formats so early was ultimately a huge advantage,” Bernier said. “It helped us establish and maintain Harvard’s leadership position in the digital preservation community.”

Ackerman and Harvard colleagues collaborated with industry peers to create international standards for digital preservation of materials. They improved their own processes and began working with Digital Preservation Services (DPS) on post-digitization workflows, like adding metadata to digital recordings (to make items easier to find) and properly storing them. Stephen Abrams, who heads DPS at Harvard Library, said the post-digitization processes are so streamlined now as to be automated.

With all these standards and systems in place, MPS staff can now focus on digitizing with the consideration that some materials are becoming obsolete more quickly than others, along with the relative research value of the material.

Vinyl LP records and even an aluminum discs are not the top priority, as they probably will be safe for years still. But media such as digital audio tape (DAT), on the other hand, is quite fragile and should be converted sooner rather than later, Ackerman said. “If you haven’t converted all your DATs, you should be worried!”

Last year, they began piloting “mass digitization” for some kinds of material, using new technology that enables several recordings to be converted at one time.

“How we get through the half a million objects will be by diversifying our approach,” Ackerman said.

They’re also planning for obsolescence — again.

“We don’t have to worry about the physical wear of materials with the preservation of digital files, but the usability of digital items is dependent on software, and that goes out of fashion,” Abrams explained. “We have to periodically review materials to make sure they’re viable in their current format, and if there’s a concern, we’ll do a migration to a different kind of file.”

While much of this work may seem daunting, or even frustrating in its repetitive nature, Abrams said passion for preserving historical records is a strong motivator — for him and his colleagues.

“You can go to Harvard’s archives, open up a drawer, and see a document from 1636 that has been preserved because of responsible stewardship,” he said. “It’s incumbent on us to show that same level of care and to pass materials on to our predecessors. In 400 years, I want someone to be able to open a drawer, metaphorically, and hear 20-year-old John F. Kennedy talking.”

And for Ackerman there is in addition the hope of more discoveries like the Kennedy recording.

“There’s a lot of material in the library’s audio-visual collections that has never been examined or heard,” she said. “You have to go through it, and you don’t really know until you start digitizing. What could be in there is anybody’s guess — but I tend to think a lot of what remains undiscovered is equal to, or better than, what we have discovered.”