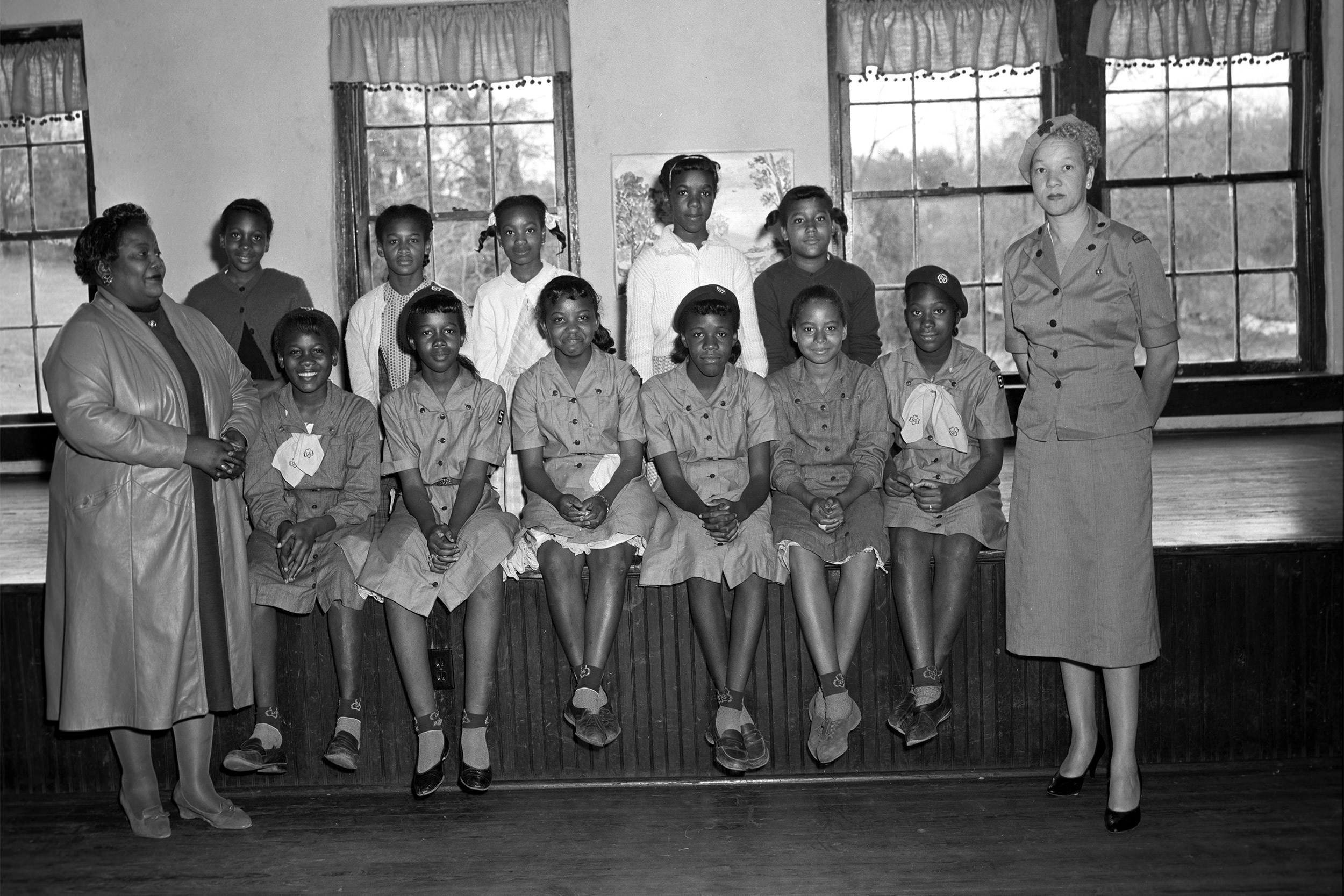

An African American Girl Scout troop photographed in Tallahassee, Florida, March 1960.

Credit: Florida Memory and the State Archives of Florida

A vision of universal, though not integrated, sisterhood

Radcliffe Fellow Amy Erdman Farrell unfurls complex racial, civil rights history of Girl Scouts

A self-described smart, chubby child, Amy Erdman Farrell remembers being teased and bullied until the day she joined a youth group devoted to female camaraderie and empowerment. “Girl Scouts changed my life,” said Farrell, professor of American studies and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Dickinson College and a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. “It was like a whole new world opened up to me of friendship and adventure where it was OK to be uncool … it was a really amazing experience.”

But it wasn’t an integrated one. Farrell, 58, who grew up in the “very segregated” industrial city of Akron, Ohio, remembers the time with her troop as “completely white.” Now at Harvard, she is working on a book about the history of the organization, founded in 1912, and its complex internal struggles with race and civil rights.

Farrell said she has been long interested in the “connections between mainstream feminism and whiteness” and more recently in how the Scouts fit into all of that. Farrell learned as a child that the organization was founded on the idea of being open to all, with each member being “a sister to every other girl.” But through the 1960s the organization’s model of sisterhood was more of a grand ideal than a reality, she said.

Her research points to deep tensions within the group involving its failure to live up to its founding credo. Committees appointed to increase inclusion ran up against “a desire not to rock the boat,” said Farrell, “and the main boat that could not be rocked was a racialized system of white supremacy in the United States.”

“Girl Scouts changed my life. It was like a whole new world opened up to me of friendship and adventure where it was OK to be uncool,” says Amy Erdman Farrell.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

That wider system was laid bare in a correspondence Farrell uncovered between two Girl Scout staff members, one white and one Black, who were trying to arrange housing for Black Girl Scouts attending the national convention being held in Long Beach, California, in 1947. When the white official realized no hotels would house Black delegates, she expressed her shock to her Black colleague, who wrote back saying “such situations are faced daily” by marginalized groups.

According to Farrell, Radcliffe’s Mary Beth and Chris Gordon Fellow, discrimination and exclusion were part of the Girl Scout’s operation for years. White troops routinely rejected Black applicants. When Black women or girls living in isolated areas far from an established unit wanted to start their own troop or become a lone scout, their requests were denied. White councils limited the number of Black troops that could be formed.

To be admitted to Girl Scout summer camp, Black girls had to prove they had camping and outdoor skills, while white girls, said Farrell, regularly arrived with no prior knowledge. Still, many Black troops sprung up across the country, as Black women eager for their daughters to have the chance to participate made it happen.

Such was the case with Josephine Holloway, who, when faced with the Tennessee council’s refusal to approve Black troops in the 1930s, simply led them on her own. The council eventually recognized Holloway’s troops in 1942, some of the first Black troops in the country, and Holloway even joined the Girl Scout’s professional staff in 1944.

Farrell explores how the early history of the Girl Scouts is a story of how the group simultaneously challenged and failed to question both racial and gender discrimination, whether in American Indian boarding schools, Japanese American incarceration camps, international centers, or in communities across the country and globe. Girls were taught that it was OK to be outgoing, she said, as long as it was in service to someone else, and there was “a lot of suppression of sexuality,” said Farrell, as a way to keep girls “innocent.”

“My book is looking at the methods by which Girl Scouts historically have encouraged what I would call this kind of proto feminism, but they did it in a way that tried not to challenge larger systems of racism, nationalism, or gender hierarchies,” said Farrell.

The research has taken her around the globe, from New York City, where the organization’s national archives are held; to the Swiss Alps, home to the international Girl Guide/Girl Scouts center; to Savannah, Georgia, birthplace of Girl Scouts founder Juliette Gordon Low.

At Harvard, Farrell has access to a trove of material housed at the Schlesinger Library related to Massachusetts chapters through the 1960s. Part of her work, she said, entails reviewing the records for material related to a range of famous women who were Girl Scouts, including one well-known, outspoken activist and educator.

“Angela Davis was a Girl Scout,” said Farrell, who has been poring over Davis’ Schlesinger archive, working with Harvard undergraduates as her Radcliffe research partners. “We haven’t found any direct references to the Girl Scouts in her papers yet, but we are not giving up.”

Farrell has chosen to end her book in the 1970s, not long after the tenure of the organization’s first Black president, Gloria Scott, and just as Frances Hesselbein was named CEO. But despite those change-makers and champions of diversity, said Farrell, there was still an “unwillingness to look back on this difficult history” and “a cementing of the narrative that Girl Scouts was always diverse. The reality is a much more complicated story.”

“I’m ending it there,” said Farrell, “so that we can be thinking deeply about the roots of this extraordinarily important institution in the United States and the world and how those early decades shape the present and future.”