Mercator celestial globe from mid-1500s resides in the Pusey Library hallway gallery, outside the Map Collection, along with its terrestrial companion.

Video and photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Library Collections in three dimensions

Ornate 16th-century globes, an Edison lightbulb, and handmade 1960s protest clothing

Most people think of libraries as keepers of two-dimensional items originally made of paper and ink — pages of manuscripts or books and photographs or other images.

While Harvard’s libraries do hold millions of books, manuscripts, and photographs, they also hold objects made of wood, metal, glass, and cloth. These 3D objects range from five years old to nearly 500 years old, and they help bring different periods and places to life.

Objects held in Harvard Library’s special collections and archives can be viewed in person by any researcher. They can also be used for teaching and learning, and some are even available to use for digital teaching.

Here’s a sampling — three objects, from three different centuries, held in three different archives at Harvard.

—Compiled by Anna Burgess/Harvard Library Communications

Edison Lightbulb, 1882, Harvard Theatre Collection

This incandescent lightbulb was manufactured by the Edison Company for the Bijou Theatre on Washington Street, in the heart of Boston’s Theater District. The Boston Bijou was the first theater in the U.S. to be entirely lit by electricity. In 1882, Thomas Edison himself supervised the installation of 644 incandescent bulbs throughout the theater.

Before electricity, theaters were lit by gas lamps and were highly prone to fire — one British engineer calculated the average lifespan of a theater in the U.S. at just 13 years. Electricity was cleaner and safer than gas, and the incandescent bulb drastically reduced the threat of fire. This lightbulb is a prime example of that technological innovation.

While it would take decades for electricity to become commonplace in homes, theaters were a place where the public could witness such advancements firsthand. Theatergoing at the time was a more democratic pastime than it is today, and theater was a major part of Boston’s cultural history, despite the city’s Puritan past. The theater district gave birth to vaudeville and incubated some of America’s most darling musicals and daring new dramas on their way to Broadway. Boston was — and in some respects still is — a theater town, and the Harvard Theatre Collection has been documenting the history of local performing arts for over a century.

The lightbulb is held at Houghton as part of an archival collection relating to the Bijou’s day-to-day management in the 1880s. Due to its fragility, it is stored away from bumping elbows and may take a bit longer to retrieve than, say, an ordinary book. But any researcher can put in an advance request and come see it. That is pretty rare — I can’t think of many opportunities where one can examine an actual Edison lightbulb without it being behind glass.

—Dale Stinchcomb, Assistant Curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection

Student protest T-shirt, 1969, Harvard University Archives

In April 1969 Harvard experienced a two-week period of student protests — including the takeover of a University administration building — over the Vietnam War and other political and social issues. This T-shirt and others like it, as well as protest posters, were printed by a group operating out of the Graduate School of Design called the Strike Artists’ Co-operative.

The shirts themselves were regular, everyday clothing — students brought their own to be printed, so some of them are pretty worn out. The silkscreen process used to print on the shirts is a lightweight, easy-to-use method. And the printing was done collectively, in the spirit of political and labor protest everywhere. The quick, handmade design is very much in the DIY spirit of the late ’60s — embodied in publications like the DIY-focused magazine Whole Earth Catalog — and is similar in style to ’60s art focused on social justice, like works by Corita Kent.

The T-shirts provide concrete evidence of the hurly-burly, spontaneous activism at Harvard, and in society more broadly, in the late 1960s. Specifically, these items reflect the turmoil of the late 1960s from the perspective of students and other participants in the protests. Several of the shirts were given to the Archives by students who protested at Harvard in 1969. Having kept the T-shirts for so many years, I assume they felt the protests represented an important part of their Harvard experience. For the Archives, these perspectives balance the perspective of University administrators, which are evident in the University records we also hold.

Today, any researcher can visit the Archives to see these items. Researchers might be interested in the history of student activism and protest, or graphic design in the 1960s. As the “social media” of their day, the T-shirts are one of the best reflections of the broader American culture during a time of political and social change.

—Robin McElheny, Associate University Archivist for Collections and Public Services

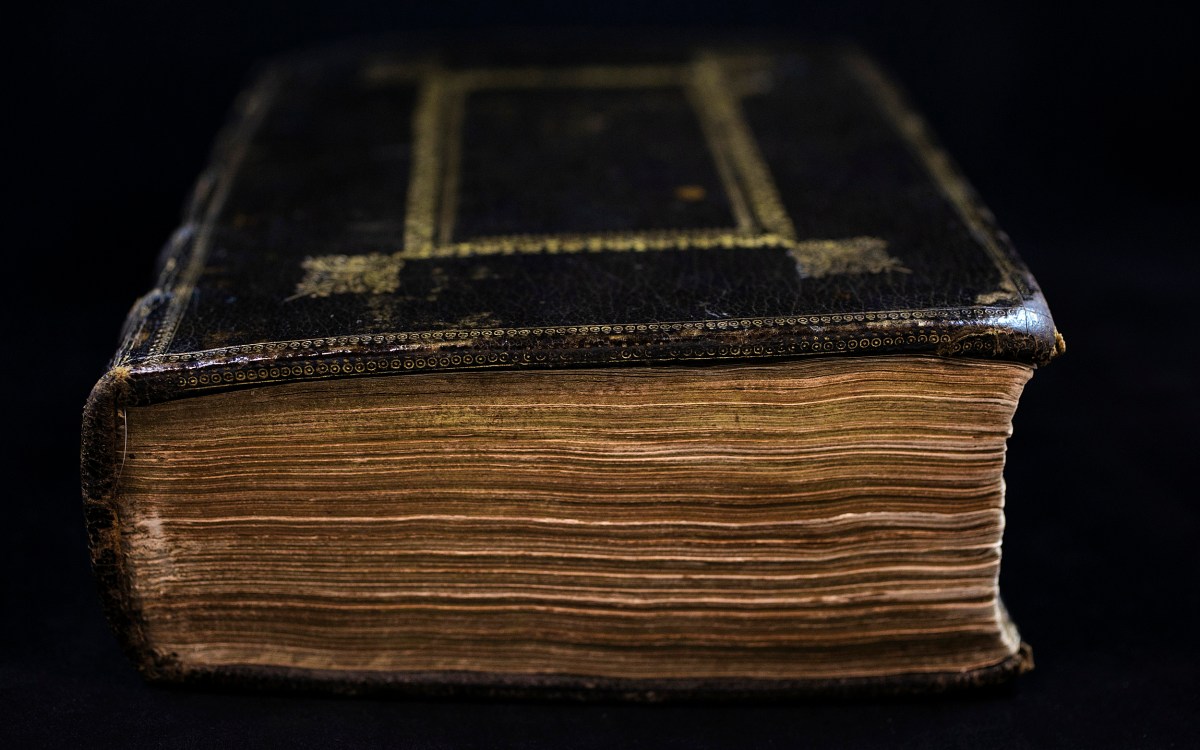

Celestial and terrestrial globes, mid-1500s, Harvard Map Collection

Gerardus Mercator started making these globes in 1541 (for the terrestrial) and 1551 (for the celestial). He continued to sell and produce them nearly until his death in 1594. They were produced originally in Louvain, Belgium, and Mercator sold them as commercial products, so they were expensive but not unattainable. They were used as scientific objects, to make precise celestial measurements and predictions as well as calculations about distance and trajectory on Earth. The globes are a great demonstration of the combination of art and science — Mercator and his workshop needed to perfect artistic practices like engraving, spherical construction, and printing, but they also developed careful mathematical calculations to ensure that the lines they printed as globe gores would line up perfectly when pasted to the sphere of the globe.

Scholars estimate that he and his workshop made hundreds, but only a few dozen remain. Harvard has, at least according to the last survey, the only paired set in North America. Because of the matching stands, our pair was probably produced together after 1551, but I can’t say precisely when. There’s a lot you can say from these globes about how Europeans were imagining the Americas in the late 1500s, which was the beginning of their colonization. So their beauty is bound up in that history of colonial violence and exploitation.

These globes were also created at an interesting inflection point in mapmaking. Mercator used many medieval and ancient sources for information on the map, from Claudius Ptolemy to Marco Polo. But he also tried to incorporate the newest science and information from European colonialists. That tension between fealty to historical sources, religious doctrine, and new scientific evidence that contradicted older ideas had been playing out in maps and atlases since about 1400 and really gives way to atlases that start to downplay the ancient sources by the end of Mercator’s lifetime.

Now, they live in the Pusey Library hallway gallery right outside the Map Collection. As with all our materials, anyone is welcome and encouraged to use them — everyone can enjoy finding all the sea monsters on the terrestrial globe and the beautiful constellations on the celestial globe.

—Dave Weimer, Librarian for Cartographic Collections and Learning