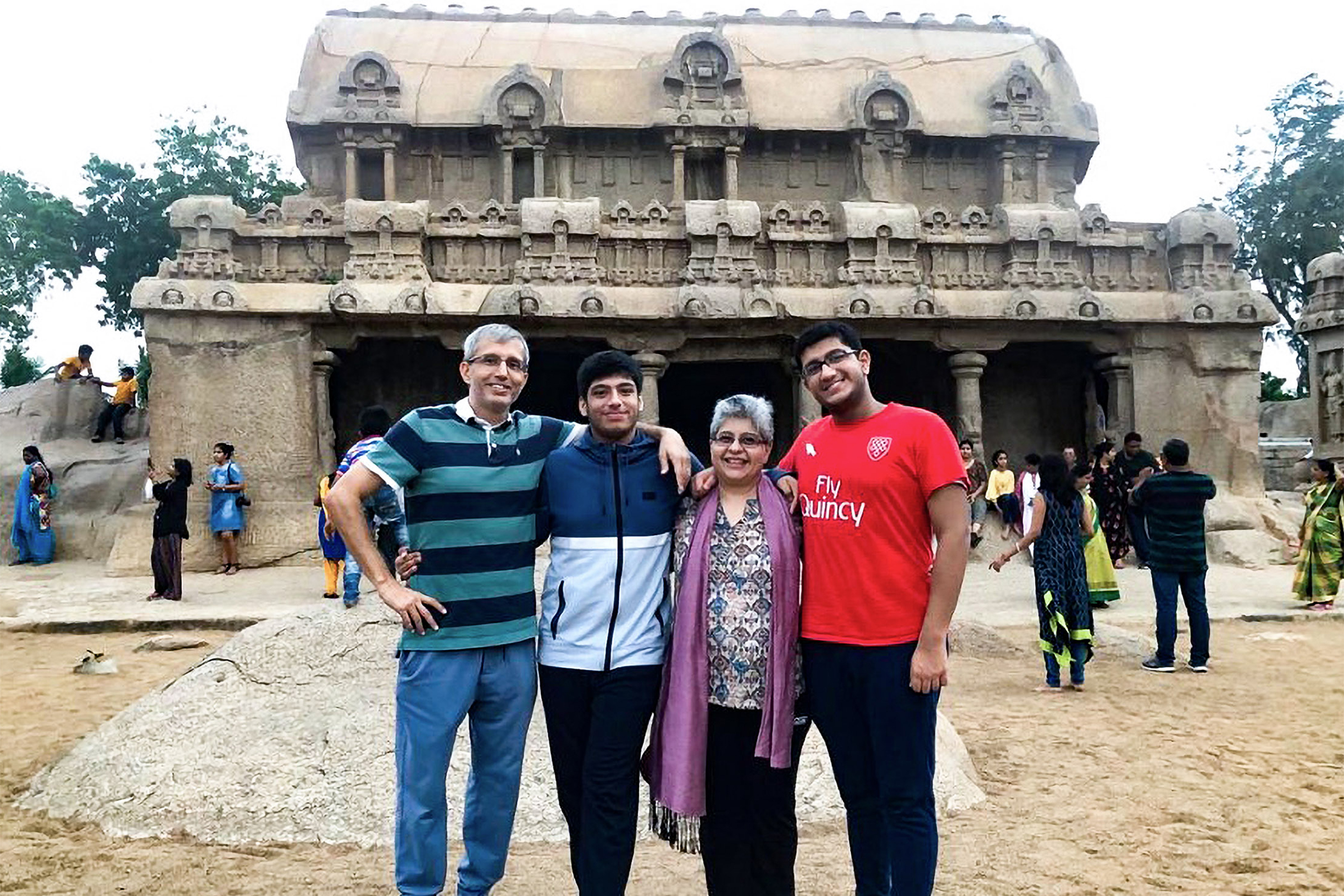

Harvard student Phiroze Parasnis traveled with his younger brother and parents in India just weeks before COVID-19 shut the country down.

Photo courtesy of Phiroze Parasnis

United by lockdown, divided by ‘Seinfeld’

For Phiroze Parasnis and his family, isolated in Mumbai, time spent together made up for lost time

This is the third entry in a three-part series about family life during the pandemic. Read the first and second.

In March 2020, India was under strict lockdown as health and government officials scrambled to contain the deadly spread of COVID-19. The country’s entire population — roughly 1.4 billion people—had been forced indoors, forbidden to leave home unless it was for food or a medical emergency.

Phiroze Parasnis and his family — younger brother Yohann Parasnis and their father Kaushik Parasnis and mother Kashmira Wadia — watched Mumbai, one of the world’s most populous cities, fall silent. Streets emptied, schools converted into field hospitals. Before long, they heard about the death of a neighbor from the virus — and then another. As the world shrunk to the size of their apartment, they tried to adjust to a smaller, scarier reality.

“We were more or less locked up in this house,” said Kaushik. The family filled their days with work, school, and cooking, and with simple joys like watching TV as a family. Binging sitcoms, including “Seinfeld,” became a popular dinner-time ritual; they made it through all 180 episodes of the 1990s hit in the space of a few months. But not everyone was a fan.

A government concentrator, Phiroze had envisioned a career at a federal, state, or local agency or in foreign affairs. But binging TV series during Emmy season with family led him down a different path and eventually an internship on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Even just bonding at the table, having a routine of every single meal watching ‘Seinfeld,’ hearing my dad complain about how he’s bored of ‘Seinfeld’ now, I think that it really added a great routine to our lives.”

Phiroze Parasnis

“It was very controversial,” said Phiroze, who will graduate from Harvard this week and is interviewing for jobs in television production. “Some people liked it; some people didn’t like it. And then they have nine seasons, so it went on and on and on. But I think even just bonding at the table, having a routine of every single meal watching ‘Seinfeld,’ hearing my dad complain about how he’s bored of [it] — I think that it really added a great routine to our lives.”

During Emmy season, Phiroze and Yohann began to “mega-binge” nominated series. Looking back, the elder brother isn’t sure how they managed to watch so many shows in so little time.

What helped, he suspects, was the siblings’ decision to turn their casual viewing into “an intellectual endeavor.” They took copious notes and discussed lighting choices, camera angles, and catchy dialogue. They even came up with their own ideas for possible pilots.

At first it just felt like a fun distraction, but it turned out to be more.

A government concentrator, Phiroze had envisioned a career at a federal, state, or local agency or in foreign affairs. But as he and his brother immersed themselves in small-screen storytelling, he gained a deeper respect for the depth, power, and political influence of TV. He opted to take the fall 2020 semester off, landing a job at an Indian news agency, where he helped cover the pandemic, the U.S. presidential election, and the massive demonstrations that met the Indian government’s plans to overhaul the country’s farming industry. The experience helped him secure an internship on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” in the summer and fall of 2021, during another break from his studies.

“The Colbert show was a great combination of news and entertainment and humor, and I think that I realized, ‘Wow, this is a perfect combination of my interests,’” he said.

“Taking time off has completely changed what I want to do in life,” he added. “It gave me so much time to just be with myself, be with my thoughts, spend time with my family, and really think about what I want to do.”

Yohann said that exploring the creative nature of television with his brother by his side rekindled his love for a different art form: music. “COVID kind of gifted us with the time to do what we wanted,” he said. The then-high school senior started teaching himself piano, learning basic chords and progressions, and gradually developed a simple melody he’d recorded on his iPhone into a full song. When restrictions eased, he made his first demo. “I think the pandemic showed me how intensely I loved [music] and enjoy doing it as not only a hobby but as something that I could possibly do in future,” he said.

And so music became another part of the family’s routine. During the lockdown, Yohann introduced his mother to contemporary disco, R&B, indie folk, and alternative rock. The family set up a small Bluetooth speaker in the kitchen, and soon Kashmira was cooking to Pink, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Camila Cabello, and others. “Yohann introduced me to so many singers — like Dua Lipa,” said Kashmira. “And it’s amazing that now I like her singing so much, we’ve agreed that we are actually going for her concert in the summer.”

* * *

Even as the family sought to make the best of their situation every day, they never lost sight of the tragedy unfolding all around them.

Kashmira won’t ever forget the eerie quiet of the Mumbai streets. In normal times, the city of 20 million would have been jammed every day with cars blaring their horns. Instead, she said, “The only thing we heard was the sound of ambulances, and that was something which really hit us.” She also recalled the heartbreaking scene of countless migrant workers forced to walk home, in some cases hundreds of miles, after the country’s vast transportation system shut down. And she remembers feeling utterly helpless when her aunt fell and broke her hip. “We just could not go to even help her, take her to the hospital. It was only someone with a pass who could admit her to the hospital. Essential workers had passes, and they were able to use the transport.”

“After three days, the operation did take place,” said Kashmira. “But with, I think, no family around, with complications, doctors involved with other things, she did not make it.”

Deserted Mumbai street in March 2020.

AP Photo/Rajanish Kakade

“After three days, the operation did take place. But with, I think, no family around, with complications, doctors involved with other things, she did not make it.”

Kashmira Wadia

Despite the toll the virus was taking, including the lives of two neighbors, the family tried their best to maintain some measure of contentment, finding comfort in their daily routines and in one another’s company. They converted a corner of the apartment into a mini-gym and took turns doing their daily workouts. They watched as birds they’d never seen before appeared on their little balcony. They even made their home a temporary salon.

Kaushik became the family barber, using a trimmer he’d ordered from Amazon. “I actually gave a haircut to all the four of us, including myself,” he said. “I gave Yohann a ‘Peaky Blinders’ Thomas Shelby haircut — which everyone in his class really enjoyed, by the way.”

One of their few disagreements involved first responders. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked people to stand on their balconies and bang pans and pots in a show of solidarity with health care workers in the early days of the pandemic, Kashmira and her sons joined in, but Kaushik refused, angered by what he considered Modi’s slow reaction to the crisis.

“I totally support, and I will give money and time and effort to, first responders,” he said. “I will take care of their children if something happens to them. But I’m not going to bang on vessels in the balcony at 5 p.m. just because the prime minister asked me to.”

“I totally support, and I will give money and time and effort to first responders. I will take care of their children if something happens to them. But I’m not going to bang on vessels in the balcony at 5 p.m. just because the prime minister asked me to.”

Kaushik Parasnis

Looking back on those difficult days of lockdown, Kaushik, a software engineer who could work from home, thinks of his family as lucky. “I would like to pay tribute to all these people who have lost their lives, and those who have helped us survive,” he said. He is also grateful for the gift of shared time. “I’m coming out of this COVID experience with that really big positive in my mind — that we, our nuclear family, got so much time together,” he said.

Phiroze will leave Harvard with a deeper sense of connection to his family and a new sense of what his future might hold. He is sad that COVID “fractured the class of 2021,” robbing him and his classmates of precious time together on campus. But it’s an absence he can live with.

“In the large scheme of things, I’d rather have [lost] this,” said Phiroze, “than lose a lot of the other things that people lost.”