Braking for badges

Theda Skocpol displays her collection of badges from early U.S. fraternal groups.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Political scientist Theda Skocpol has traveled U.S. collecting ‘little works of art’ that reflect nation’s history

As an expert on U.S. democracy, Theda Skocpol gets invited to speak at conferences all over the country.

Organizers, take note: She’ll more eagerly accept the invitation if the event happens to sit in close proximity to an antique shop where she can search for badges from America’s earliest fraternal groups, membership associations, and labor unions.

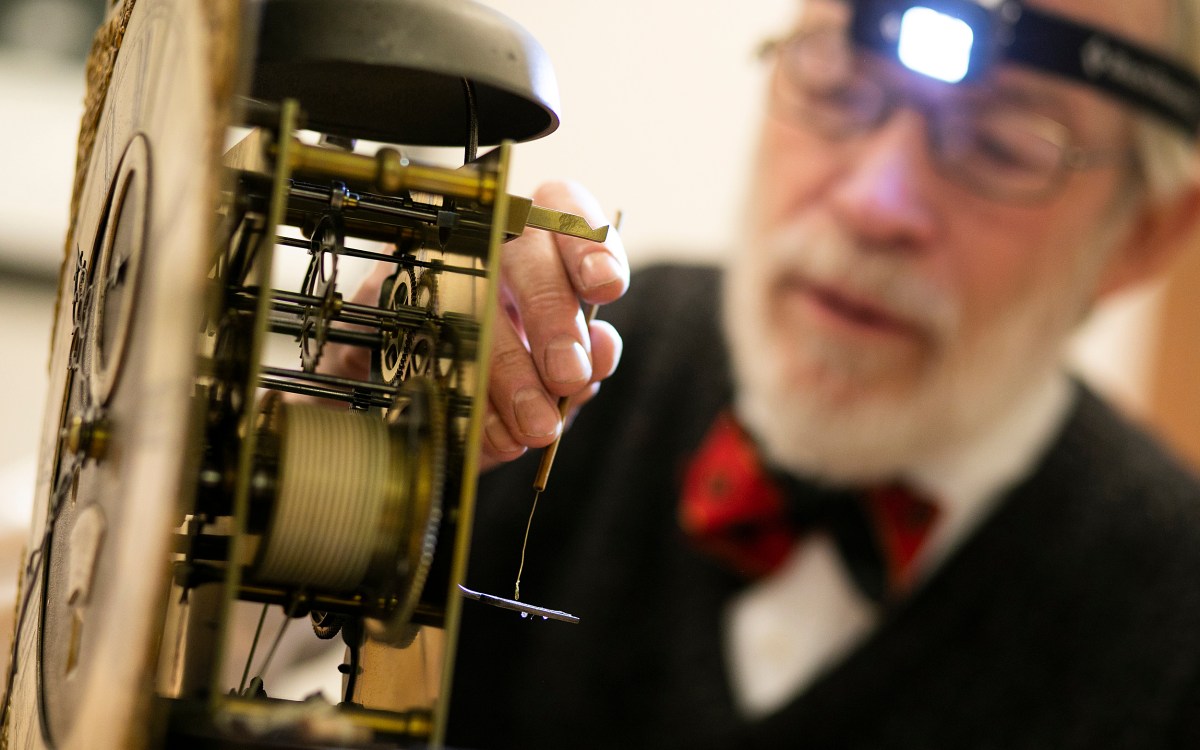

“Once I discovered these, I became obsessed with them,” said Skocpol, Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology, whose collection of 2,100 badges spans all 50 states. “I decided that they were little works of art and that I needed to find them. These are beautiful badges that communicate the symbols of the overall group and usually, but not always, the state, the locality, and the name of the particular lodge or chapter, so I get to see how they named them.”

Badges with pin tops that still have their ribbons are seven to 11 inches and usually made of silk; some are decorated with medals, some embroidery, some fringe trim. The members and leadership of thousands of regional and national groups — brotherhood and sisterhood associations, ethnic organizations, labor unions — pinned them to their shirts, dresses, jackets.

Among Skocpol’s most prized possessions are two-sided badges with the front designed for celebrations and a black and silver backside to be worn at funerals.

“Still today, if you go to any Irish fireman’s funeral parade, you’ll still see many of the firemen wearing these badges like these,” she said, pointing to an Ancient Order of Hibernians badge from 1886 encased in a shadow box on her dining room table. “It has a neck rope and very elaborate designs and tassels. And it’s what they wore for parades and when somebody died.”

“Once I discovered these, I became obsessed with them. I decided that they were little works of art and that I needed to find them.”

Theda Skocpol, pictured below

Skocpol first became familiar with the badges, and the groups behind them, in the late 1990s, when she was researching her award-winning book “Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life.”

“The book came out and I was much under demand to speak about it,” she said. “I think people in every small college in America were surprised because they’d contact me and I’d say, ‘Yes, I’d love to come to rural Missouri!’ I mean, I probably would have anyway because I’m a very big believer in getting out there and seeing the country. But I also knew I could rent a car and check out some antique malls.”

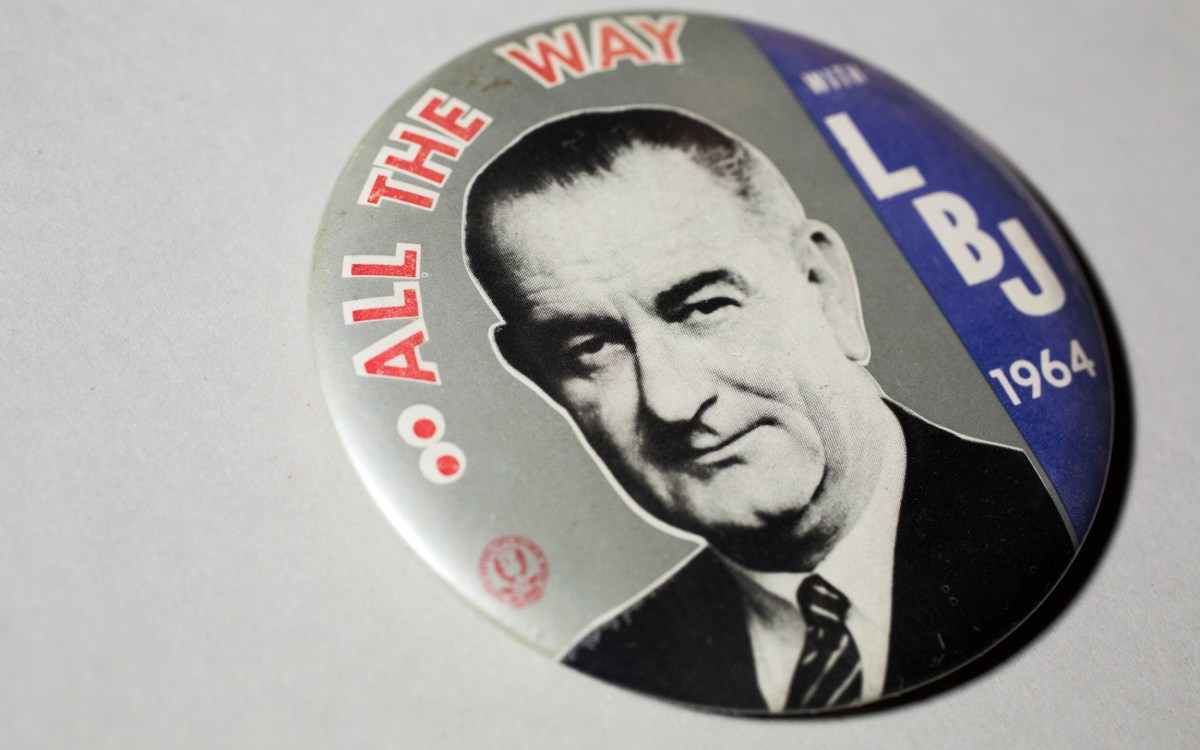

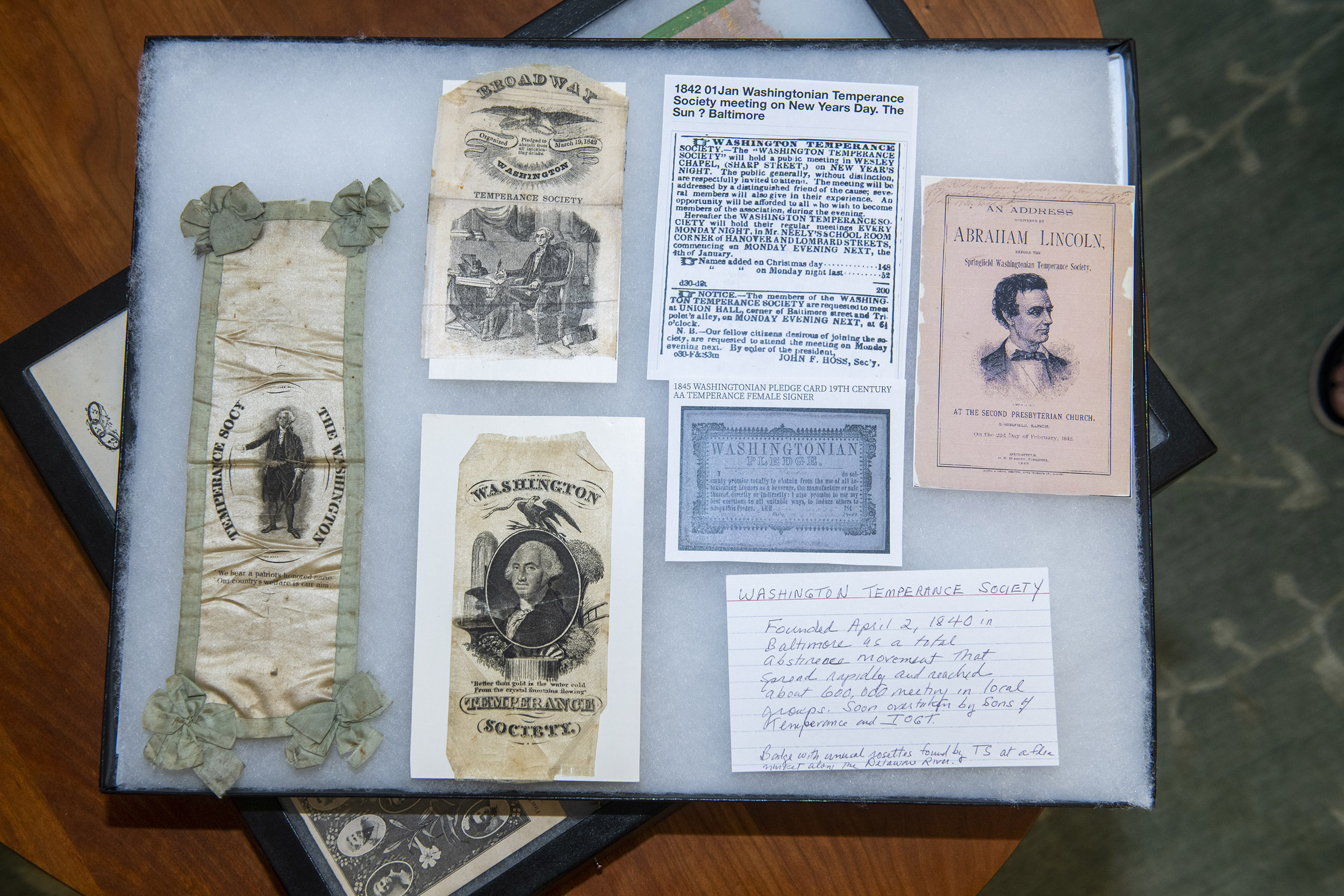

In Michigan, on the Upper Peninsula, Skocpol found ribbon badges from Finnish-Americans who had worked as loggers or in the lumber industry. In Maine, she found badges from the only two lodges affiliated with the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, an African American fraternal group. Her oldest badge, green-edged with rosettes, is an artifact of the 1840s Washington Temperance movement. She discovered it decades ago while nosing around “the crudest of flea markets” along the Delaware River. The memory hasn’t faded.

“I knew immediately what it was, and the seller had a high price of $200,” she said. “Careful not to show any excitement, I asked if she would take $100 and when she agreed, pulled out the money very fast. I love it and I love the story. I basically found it where Washington crossed the Delaware.”

The history contained in Skocpol’s collection is American in more ways than one, hinting at the violence and discrimination that have brought the nation to the breaking point. Inside the glass cases arranged on her dining room table one recent morning were selections from among 80 different African American groups. Their names, she said, “are particularly touching because most of them emerged after the Civil War, and local lodges have names like United Sons and Daughters of the Morning Light, or are named after Lincoln or Charles Sumner or local Black leaders.”

Ribbons from West Virginia unions and Jewish groups.

The typical cost of a badge has risen from $5-$15 to $25 over the past 20 years, with rare or elaborate items selling for hundreds of dollars. Skocpol hopes to digitize her holdings and someday find a home for the physical collection at a museum. While the historical value of the badges has been her guiding motivation, personal history — her own and that of fellow citizens seeking details about their ancestry — has enriched her journey.

“I love to see America,” Skocpol said. “I remember once hitting a whole series of antique malls along the Ohio River where Indiana meets Ohio. The thing about antiquing is — you’re going to find what you’re going to find, you almost certainly are not going to find what you set out to find. And these things travel. Stuff from Maine can end up anywhere because people travel, or their grandkids take it with them, and then move somewhere. When people contact me about a speech or an article they found on the internet, I always write back to people and tell them what I know. People want to know what their grandparents or great-grandparents were doing. It’s a scholarly collection, but I want them available to someone who’s trying to understand their family’s connection as well as our nation’s varied history.”